Silver Veins, Iron Wills: The Enduring Legacy of Tombstone’s Mines

Tombstone, Arizona. The name alone conjures images of dusty streets, legendary gunfights, and iconic figures like Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday. The "Town Too Tough To Die" is immortalized in Western lore, a symbol of the untamed American frontier. Yet, beneath the veneer of its famous shootouts and saloons, lies the true foundation of its existence and its ultimate struggle: the rich silver mines that gave birth to the town and, paradoxically, sealed its fate. The story of Tombstone’s mines is one of immense wealth, relentless human ambition, technological marvels, and the unforgiving power of nature, a narrative far more profound and enduring than any single gunfight.

Our journey into the heart of Tombstone begins not with a six-shooter, but with a prospector’s pickaxe. In 1877, a determined but unassuming prospector named Ed Schieffelin ventured into the Apache-dominated Arizona Territory, despite warnings from soldiers at Camp Huachuca that "all you’ll find out there is your tombstone." Undeterred, Schieffelin pressed on, and his persistence was rewarded. He discovered a significant silver lode, which he aptly named "Tombstone" in a defiant nod to the grim prophecy. His first claim, the "Tough Nut," would prove to be one of the richest, sparking a silver rush that transformed a desolate patch of desert into a booming metropolis.

Within a few years, Tombstone exploded. From a handful of tents and a crude assay office, it mushroomed into a vibrant, albeit chaotic, town boasting a population that swelled to over 15,000 residents in less than a decade. The streets, initially mud and dust, soon bustled with miners, gamblers, merchants, prospectors, and entrepreneurs of every stripe. Saloons and dance halls sprang up overnight, alongside respectable banks, newspapers, and opera houses. This rapid development was fueled by the seemingly endless flow of silver ore extracted from beneath the earth.

The most famous mines, alongside the Tough Nut, included the Contention, the Grand Central, the Lucky Cuss, and the Way Up. These weren’t mere holes in the ground; they were sophisticated operations for their time, employing hundreds of men working in shifts around the clock. Miners descended hundreds of feet into the earth, often in cramped, dimly lit shafts, hacking away at silver-bearing rock. The work was arduous, dangerous, and often fatal. Cave-ins, explosions from black powder, and respiratory diseases from dust were constant threats. Yet, the promise of wealth, even if most of it flowed to the mine owners, kept the flow of labor steady.

The silver extracted from Tombstone’s mines was staggering. Estimates vary, but historical accounts suggest that between $85 million and $100 million worth of silver was pulled from the ground during its peak years in the 1880s. To put this into perspective, even without adjusting for inflation, this was an astronomical sum, equivalent to billions in today’s currency. This wealth not only built Tombstone but also contributed significantly to the national economy and fueled the expansion of the American West.

However, the very geology that blessed Tombstone with silver also held the seeds of its destruction. As the miners dug deeper, they encountered an adversary more formidable than any outlaw: water. The Gila Conglomerate, a geological formation underlying the silver veins, acted as a massive underground reservoir. Initially, water seeped into the lower levels, a nuisance that could be managed with simple pumps. But as shafts descended below 500 feet, the problem escalated dramatically, turning into a relentless, overwhelming flood.

The fight against the water became the defining struggle of Tombstone’s mining era. Mine owners invested heavily in increasingly powerful pumping technology. The solution came in the form of massive Cornish pumps, engineering marvels imported from England. These colossal steam-driven engines, with their huge walking beams and intricate mechanisms, were capable of lifting thousands of gallons of water per minute. The most famous of these were the pumps at the Grand Central and Contention mines, towering structures that consumed vast quantities of timber and coal to fuel their boilers.

"The clang and hiss of the great Cornish pumps became the heartbeat of Tombstone," wrote one contemporary observer. "Day and night, they fought the water, a mechanical army holding back an underground sea." The battle was epic, a testament to human ingenuity and stubbornness. Companies pooled resources, forming the "Grand Central Consolidated Mining Company" and the "Contention Consolidated Mining Company" to fund the monumental expense of operating these pumps. Maintaining the pumps was a round-the-clock endeavor, requiring skilled engineers, mechanics, and a steady supply of fuel.

Despite their power, the Cornish pumps merely held the water at bay; they couldn’t defeat it entirely. The cost of running them was astronomical, eating into the profits, especially as silver prices began to fluctuate. The mines became a race against time and nature. The water was always there, waiting for any weakness, any lapse in vigilance.

The inevitable tipping point arrived in 1886. On May 26th, a fire broke out in the Grand Central Mine. The flames quickly engulfed the timber structures and supports within the shaft, causing immense damage and, critically, disabling the massive Cornish pump. With the Grand Central pump out of commission, the water levels in all the interconnected mines began to rise inexorably. Efforts to repair the damage and restart the pumps were hampered by the rising water and the sheer scale of the disaster.

The fire was a death knell. Within months, most of the major mines were flooded beyond the capacity of the remaining pumps to clear them. The cost of pumping, even if it could be restored, was simply too high given the declining price of silver and the increasing depth of the workings. One by one, the mines began to shut down. The miners, the lifeblood of the town, moved on to other strikes. The boom ended with a whimper, not a bang, as the water claimed its victory.

"The water defeated us, not the silver," lamented one former mine owner, a sentiment echoed by many who watched the town’s fortunes recede. Tombstone, the "Town Too Tough To Die," had been brought to its knees by an enemy it couldn’t shoot, bribe, or outwit.

The early 20th century saw sporadic attempts to revive Tombstone’s mining industry. With advances in electric pumping technology, there was hope that the flooded mines could be drained and new veins explored. The Contention, Grand Central, and other mines were briefly reopened, and some silver was extracted. However, the costs remained high, silver prices didn’t always justify the investment, and the sheer volume of water proved to be a persistent, overwhelming challenge. The final serious attempts to dewater and work the mines largely ceased by the 1930s.

Today, the mines of Tombstone are silent, their shafts flooded and largely inaccessible. The hum of the Cornish pumps is long gone, replaced by the whispers of history carried on the Arizona wind. Yet, their legacy endures. The wealth they generated built the town, its legendary characters, and its enduring place in American folklore. Without the silver, there would have been no Tombstone, no Earp, no OK Corral. The mines were the economic engine that drove the entire saga.

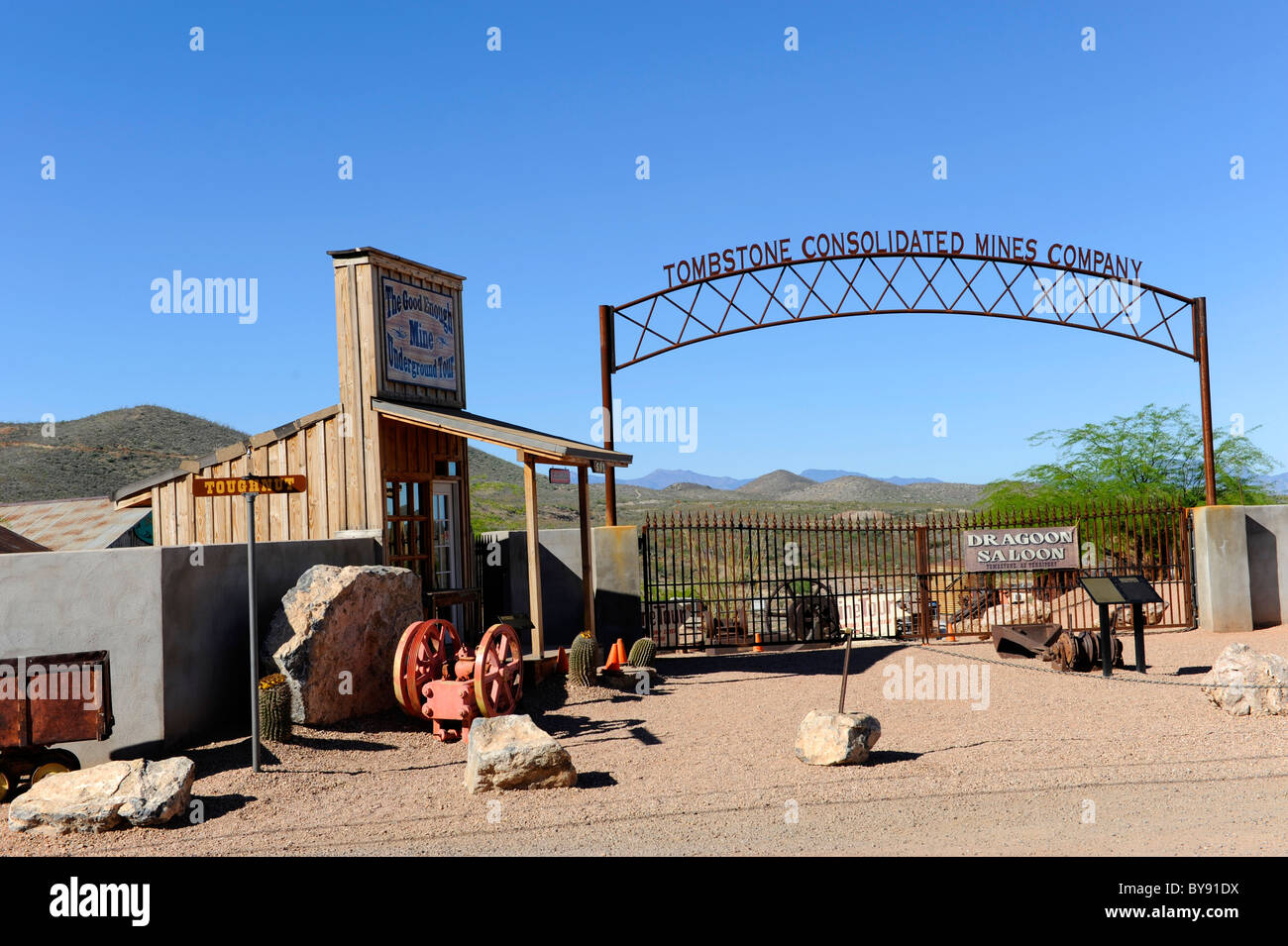

Modern Tombstone embraces its dual identity. Tourists flock to see the reenactments, walk the historic streets, and visit the iconic landmarks. But the deeper story, the true struggle that defined its rise and fall, lies beneath the ground. The historic sites, like the Tombstone Courthouse State Historic Park, and local museums, such as the Good Enough Mine Tour (which takes visitors into a smaller, shallower mine that wasn’t flooded to the same extent as the major ones), strive to tell the story of the miners and the epic battle against the water. These efforts serve as a vital reminder that the town’s fame rests not just on its Wild West bravado, but on the back-breaking labor and unyielding spirit of those who delved deep into the earth, chasing the glimmer of silver.

The story of Tombstone’s mines is a microcosm of the American West: a tale of ambition, opportunity, technological innovation, and the raw, often brutal, confrontation between human will and the forces of nature. It’s a reminder that beneath the celebrated legends of cowboys and outlaws, the true bedrock of many frontier towns was the earth itself, yielding its treasures and then reclaiming them. The silver veins of Tombstone may be exhausted, and its mines drowned, but their enduring legacy continues to shape the identity of the "Town Too Tough To Die," a testament to the powerful, often unseen, forces that truly built the West.