The Great Plains’ Bloodstained Canvas: Unpacking the Sioux Wars

The American West, a landscape etched with myth and struggle, holds within its vast expanse the echoes of a profound conflict: the Sioux Wars. More than a series of isolated skirmishes, these were a sprawling, decades-long confrontation, born from an irreconcilable clash of cultures, an insatiable hunger for land and resources, and a tragic cascade of broken promises. From the mid-19th century to the cusp of the 20th, the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota Sioux nations, along with their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies, fought desperately to preserve their way of life against the relentless tide of American expansion. Their struggle, marked by both valiant resistance and heartbreaking defeat, reshaped the continent and left an indelible scar on the soul of a nation.

The Seeds of Conflict: A Clash of Worlds

At its core, the Sioux Wars were a collision between two diametrically opposed worldviews. For the Lakota Sioux, the Great Plains were their ancestral home, a sacred expanse where life revolved around the vast buffalo herds. Their nomadic existence was intricately tied to the rhythm of nature, their spiritual beliefs interwoven with the land, the sky, and the animals they hunted. Land was not a commodity to be owned but a living entity to be respected and shared. "My lands are where my dead lie buried," famously declared Crazy Horse, embodying this profound connection.

In stark contrast, the burgeoning United States viewed the West through the lens of Manifest Destiny—a divinely ordained right to expand westward, bringing "civilization" and progress. Land was property, a resource to be surveyed, bought, sold, and exploited for its agricultural potential, timber, and mineral wealth. The indigenous inhabitants were seen as obstacles to this progress, either to be assimilated into American society or removed from their ancestral lands.

Early interactions, often marked by the fur trade, were relatively peaceful. However, the discovery of gold in California in 1848 triggered a massive westward migration. The Bozeman Trail, a shortcut through prime Sioux hunting grounds, became a flashpoint. Wagons, settlers, and prospectors streamed through, disrupting buffalo migrations and encroaching upon lands guaranteed by earlier, often vaguely understood, treaties.

The Shifting Sands of Treaties and Gold

The U.S. government’s primary tool for managing Native American relations was the treaty system. The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, intended to establish defined tribal territories and ensure safe passage for settlers, was a monumental failure. The Sioux, accustomed to fluid boundaries and communal land use, did not fully grasp the implications of fixed lines on a map. Furthermore, the treaty was almost immediately violated by American expansion, setting a precedent of broken promises that would fuel decades of conflict.

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills, or Paha Sapa, in 1874 proved to be the ultimate catalyst for the final, most devastating phase of the Sioux Wars. For the Lakota, the Black Hills were the sacred heartland of their universe, a place of spiritual power and renewal. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty had explicitly guaranteed the Lakota exclusive ownership of the Great Sioux Reservation, which included the Black Hills, and stipulated that no white person could settle there without their consent.

However, the allure of gold was too strong. Despite the treaty, prospectors poured into the Black Hills, protected by military detachments, including the infamous 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. His expedition’s confirmation of gold effectively sealed the fate of the treaty and the Sioux’s traditional way of life. When the U.S. government attempted to buy the Black Hills, Sitting Bull famously retorted, "We want no white men here. The Black Hills are mine. I did not give them to you." His words captured the essence of the Sioux’s defiant refusal to relinquish their sacred lands.

The Flames of War Ignite: Red Cloud’s Triumph and Custer’s Folly

The Sioux Wars were not a single event but a series of distinct campaigns. Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868), fought over the Bozeman Trail, stands as a rare example of a Native American victory. Under the brilliant leadership of Red Cloud, the Lakota, along with their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies, successfully harassed and besieged U.S. forts, ultimately forcing the government to abandon the trail and sign the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. This victory, however, was a temporary reprieve, merely delaying the inevitable confrontation over the Black Hills.

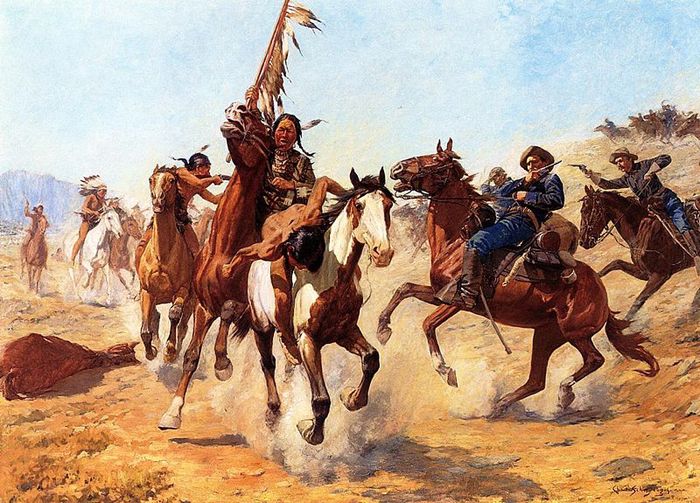

The Great Sioux War of 1876-77 was the climactic chapter. Fueled by the Black Hills gold rush and the U.S. government’s demand that all "hostile" Lakota report to agencies or be considered at war, it pitted the full might of the U.S. Army against the combined forces of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The most iconic moment of this war, and arguably the entire conflict, was the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876.

Custer, eager for glory, disastrously divided his forces and attacked a massive encampment of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. What followed was a complete rout, with Custer and over 200 of his men annihilated. "Custer’s Last Stand" sent shockwaves across America, igniting a thirst for vengeance that galvanized public support for the war. The immediate effect was a redoubling of military efforts. General Philip Sheridan, a proponent of total war against Native Americans, famously declared, "The only good Indian I ever saw was a dead Indian." While likely apocryphal, this sentiment reflected the brutal reality of U.S. policy. The victory at Little Bighorn, though morale-boosting, was ultimately a pyrrhic one for the Sioux, accelerating their eventual defeat.

The Ghost Dance and the Wounded Knee Massacre

By the late 1880s, the buffalo were virtually extinct, a deliberate policy by the U.S. Army to destroy the Plains Indians’ primary food source and undermine their independence. Confined to reservations, stripped of their land and culture, and ravaged by disease and poverty, the Sioux turned to spiritual revival. The Ghost Dance, a prophetic movement promising the return of the buffalo and their ancestors, and the disappearance of white settlers, swept through the reservations.

To the desperate Sioux, it offered hope; to the fearful white authorities, it appeared as a prelude to another uprising. The U.S. government, paranoid after Little Bighorn, overreacted. On December 29, 1890, the 7th Cavalry, Custer’s old regiment, intercepted a band of Miniconjou Lakota led by Chief Big Foot near Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. While attempting to disarm them, a shot was fired—whether accidental or deliberate remains debated—triggering a brutal massacre.

Hundreds of unarmed or lightly armed Lakota, many of them women and children, were gunned down by Gatling guns and rifles. Estimates range from 150 to 300 dead, compared to 25 soldiers killed, many by friendly fire. The Wounded Knee Massacre effectively marked the end of large-scale armed resistance by Native Americans in the West. It was a tragic, bloody exclamation point on the Sioux Wars, symbolizing the utter subjugation of a proud people.

A Shattered Legacy: The Enduring Scars

The effects of the Sioux Wars were profound and devastating, particularly for the Lakota and other Plains tribes.

- Loss of Land and Sovereignty: The most immediate and enduring effect was the near-total loss of their ancestral lands. The vast Great Sioux Reservation was whittled down to a fraction of its original size, fragmented into smaller, isolated reservations. Their sovereignty was extinguished, replaced by the paternalistic wardship of the U.S. government.

- Cultural Devastation: The forced removal from their lands, the extermination of the buffalo, and the imposition of reservation life systematically dismantled the Sioux’s traditional culture. Children were forcibly taken to boarding schools, where their languages, customs, and spiritual beliefs were suppressed in an attempt to "kill the Indian to save the man." This policy inflicted deep intergenerational trauma.

- Poverty and Health Crises: Confined to barren lands, dependent on government rations, and vulnerable to diseases, the Sioux faced widespread poverty, malnutrition, and poor health outcomes that persist to this day.

- Psychological and Spiritual Trauma: The experience of warfare, displacement, and cultural genocide left deep psychological and spiritual wounds, manifesting as historical trauma that continues to impact communities.

For the United States, the Sioux Wars solidified its control over the trans-Mississippi West, opening vast territories for settlement, ranching, and resource extraction. It contributed to the myth of the "conquest of the West" and the American frontier spirit. However, it also left a dark stain on the nation’s history, a testament to the brutal cost of expansion and the systematic dispossession of indigenous peoples.

Today, the legacy of the Sioux Wars continues to resonate. Descendants of the warriors and survivors strive to revitalize their languages, cultures, and traditions. Land claims, particularly concerning the Black Hills, remain a contentious issue. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Black Hills were illegally taken, offering financial compensation, which the Sioux have largely refused, demanding instead the return of their sacred land.

The Sioux Wars serve as a powerful reminder of the destructive consequences when different civilizations collide, driven by greed and a failure to understand or respect one another. They underscore the importance of remembering history, not just for the victors, but for all who suffered, so that the lessons learned from the bloodstained canvas of the Great Plains might guide a more just and equitable future.