Steel Veins Through Stone Hearts: The Audacious Saga of the Central Pacific Railroad

May 10, 1869. Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. Under a vast, indifferent sky, two locomotives – the Central Pacific’s "Jupiter" and the Union Pacific’s "No. 119" – stood nose to nose, their steam hissing, an emblem of a nation finally stitched together. As Leland Stanford, former California governor and president of the Central Pacific, awkwardly swung a silver maul to strike the golden spike, the resounding "DONE" telegraphed across the continent was not merely an announcement of completion; it was the triumph of an audacious dream, a testament to human will, and a monument built on the backs of thousands, many of whom remain unsung.

The story of the Central Pacific Railroad is a saga of ambition, engineering marvel, cutthroat finance, and immense human sacrifice. It is the tale of how a small group of Sacramento merchants, fueled by the vision of a driven engineer, dared to challenge the formidable Sierra Nevada mountains, transforming the American West and forging a new chapter in the nation’s destiny.

The Dream Takes Root: Judah’s Obsession

The idea of a transcontinental railroad had captivated American imaginations for decades, a tangible expression of Manifest Destiny. Yet, the sheer scale of the undertaking, particularly the challenge of crossing the towering Sierra Nevada, seemed insurmountable. That is, until Theodore Dehone Judah arrived. A brilliant, almost obsessive, civil engineer, Judah became known as the "Crazy Judah" for his singular focus. He spent years meticulously surveying routes through the Sierra, convinced he had found a practical pass. His relentless advocacy led him to Washington D.C., where he tirelessly lobbied Congress, and then back to California, where he sought financial backing.

Judah’s fervent belief eventually captivated four shrewd Sacramento businessmen: Collis P. Huntington, a cunning hardware merchant; Leland Stanford, a politician and grocer; Charles Crocker, a dry goods merchant; and Mark Hopkins, a quiet but astute bookkeeper. These men, later famously dubbed the "Big Four" or "The Associates," initially scoffed at Judah’s audacious proposal, but his detailed surveys and persuasive arguments eventually won them over. On June 21, 1861, the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California was incorporated.

The Big Four, though initially cautious, quickly proved to be a formidable combination. Huntington handled the vital lobbying and purchasing in the East, often employing dubious tactics to secure favorable legislation and supplies. Stanford provided political influence, Crocker managed the construction with an iron fist, and Hopkins kept the books with meticulous, often ruthless, efficiency. Their collective ambition, however, was as vast and untamed as the landscape they sought to conquer.

Battling the Sierra: An Engineering Nightmare

The Central Pacific’s segment of the Transcontinental Railroad was arguably the most challenging. While the Union Pacific enjoyed the relatively flat plains, the CPR faced the granite ramparts of the Sierra Nevada almost immediately after leaving Sacramento. Construction officially began in January 1863, but progress was agonizingly slow. The first 18 miles took nearly two years to complete, a stark contrast to the miles the Union Pacific would lay across the plains in a single day.

The sheer scale of the engineering task was unprecedented. "It was literally a battle against nature," writes Stephen E. Ambrose in Nothing Like It In The World. "Every foot of track had to be earned." The mountains presented a relentless series of obstacles: steep grades, narrow ridges, deep ravines, and solid granite peaks. Tunnels, an absolute necessity, had to be blasted through solid rock, often at altitudes where winter snows could bury men and equipment under dozens of feet of snow.

The Summit Tunnel, a 1,659-foot bore through the Donner Pass, became the focal point of their struggle. Men worked around the clock, drilling by hand, often in freezing temperatures, using black powder and later the more volatile nitroglycerin. Crocker, ever the taskmaster, famously ordered work to proceed from both ends of the tunnel and from a shaft sunk from the top, allowing for four faces to be attacked simultaneously. The logistical nightmare of transporting all equipment – rails, ties, locomotives, food, and blasting powder – up the steep grades, often over rudimentary roads and temporary tracks, was a feat in itself. Winter brought blizzards, avalanches, and conditions so severe that men lived and worked in snow tunnels, only seeing daylight when they emerged for supplies.

The Unsung Backbone: Chinese Laborers

Perhaps the most critical, yet least recognized, factor in the Central Pacific’s success was its workforce. Initially, the CPR struggled to attract and retain white laborers, who preferred the lure of Nevada silver mines or better-paying jobs. Charles Crocker, facing a critical labor shortage, reluctantly suggested employing Chinese immigrants, a notion initially met with skepticism and prejudice. "They are not strong enough," argued one foreman. Crocker’s response was pragmatic: "They built the Great Wall, didn’t they?"

Beginning in 1865, thousands of Chinese laborers, many fleeing poverty and unrest in their homeland, were recruited. They quickly proved invaluable. Disciplined, hardworking, and willing to take on the most dangerous tasks, they formed the backbone of the Central Pacific’s construction effort. They hung precariously from ropes on sheer cliff faces, chiseling out ledges for the tracks. They blasted tunnels, enduring suffocating dust, noxious fumes, and the constant threat of premature explosions. They worked through brutal winters, often living in rudimentary camps and snow tunnels, suffering from frostbite, scurvy, and avalanches.

Their contributions, however, came at a terrible price. Casualty rates were alarmingly high, though official records are scarce and often downplayed. Thousands are estimated to have died from accidents, explosions, disease, and the elements. Despite their vital role, they faced blatant discrimination, paid less than their white counterparts, denied the same housing and food, and were largely excluded from the celebratory narratives of the railroad’s completion. It is a profound historical injustice that their faces rarely appear in the iconic photographs of the Golden Spike ceremony, and their stories were long marginalized. "The Chinese were not seen as equals," historian Gordon H. Chang notes, "but as a disposable means to an end." Their silent, stoic labor, however, carved a path through mountains and into the fabric of American history.

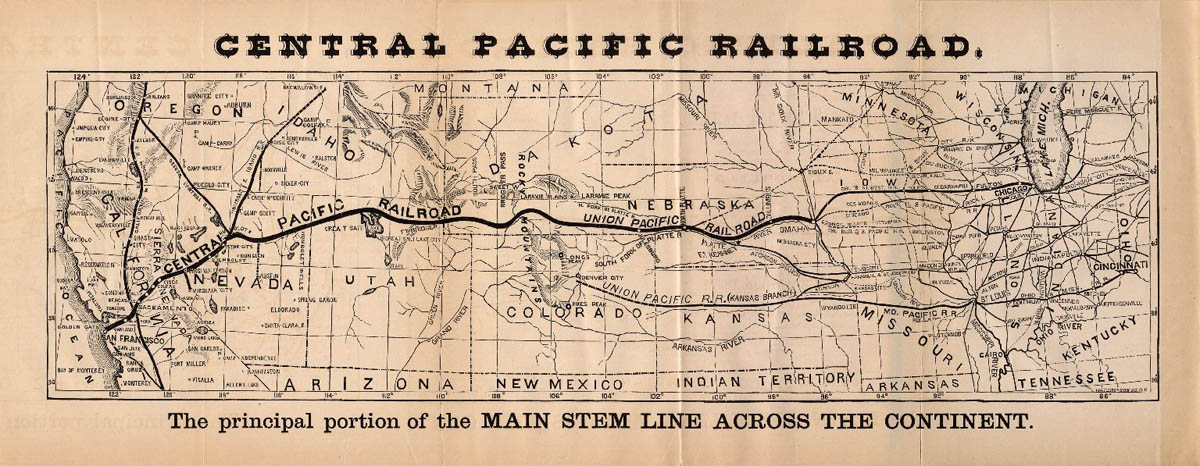

The Race Across the Desert: Union Pacific vs. Central Pacific

As the Central Pacific clawed its way out of the Sierra, a fierce rivalry with the Union Pacific Railroad intensified. Both companies were heavily incentivized by government subsidies, receiving land grants and financial bonds for every mile of track laid. This created a frantic, often chaotic, race across the continent. The Union Pacific, starting from Omaha, Nebraska, had the advantage of relatively flat terrain, but faced constant skirmishes with Native American tribes defending their ancestral lands. The CPR, having conquered the mountains, now sped across the Nevada desert, laying track at an astonishing pace.

The competition led to "grade wars," where both companies laid parallel tracks in areas, hoping to claim more government subsidies. The federal government eventually intervened, setting Promontory Summit as the meeting point. The race was on to reach it first, with both companies pushing their crews to the brink. Charles Crocker, known for his relentless drive, reportedly bet Union Pacific’s Thomas Durant $10,000 that his Central Pacific crews could lay ten miles of track in a single day – a feat considered impossible. On April 28, 1869, with Chinese laborers forming the bulk of the workforce, the Central Pacific achieved the impossible, laying 10 miles and 56 feet of track in just 12 hours, a record that stood for decades. This extraordinary effort underscored the capabilities of the Chinese crews and Crocker’s unyielding leadership.

The Golden Spike: A Nation Connected

The final days leading up to the meeting were a whirlwind of activity. On May 10, 1869, a crowd of dignitaries, photographers, and workers gathered at Promontory Summit. Telegraph wires had been specially run to the site, ready to transmit the news to an eager nation. After a series of ceremonial spikes were driven – including the famous "Golden Spike" from California, a silver spike from Nevada, and a gold, silver, and iron spike from Arizona – Leland Stanford raised the silver maul. His first swing missed the spike entirely, hitting the rail, but the telegraph operator, anticipating the moment, tapped out "DONE" to the waiting world.

The news spread like wildfire. Bells rang, cannons fired, and celebrations erupted from San Francisco to New York. The continental divide was conquered, the vast wilderness tamed. Travel time from coast to coast, once a perilous months-long journey, was slashed to a mere week. "We have opened a pathway for the commerce of the world," declared Leland Stanford in his speech at the ceremony.

Legacy and Lessons

The immediate impact of the Transcontinental Railroad was profound. It ignited westward expansion, facilitated trade, spurred the growth of new towns, and created a truly national economy. It symbolized America’s ingenuity and industrial might, uniting a nation still healing from the wounds of the Civil War.

Yet, the legacy of the Central Pacific is complex. It represents not only triumph but also the darker aspects of American expansion: the exploitation of labor, the displacement of Native Americans, and the environmental changes wrought upon the landscape. The immense contribution of the Chinese laborers, though critical to the railroad’s completion, was long overshadowed by prejudice and exclusion, a historical oversight that modern scholarship is only now beginning to rectify.

The Central Pacific Railroad stands as an enduring testament to human ambition and resilience. It was an undertaking born of an audacious dream, executed by engineers, financiers, and thousands of laborers who battled mountains, deserts, and the harshest elements. It reshaped a continent, connected a nation, and laid the steel veins through stone hearts that continue to resonate in the grand narrative of American progress. It reminds us that behind every monumental achievement lies not just visionary leadership, but the sweat, toil, and often unacknowledged sacrifice of countless individuals.