Stonewall’s Storm: The Audacious Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862

In the annals of military history, few campaigns burn as brightly with the fires of strategic brilliance and audacious execution as Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862. It was a whirlwind of movement, deception, and decisive blows that defied conventional military wisdom, cemented Jackson’s legendary status, and bought precious time for the beleaguered Confederate capital of Richmond. In just over three months, Jackson, with a force that rarely exceeded 17,000 men, would march an astonishing 649 miles, fight five major battles, engage in numerous skirmishes, and defeat three separate Union armies totaling over 60,000 troops, all while suffering minimal losses. It was a performance that stunned the North, electrified the South, and remains a masterclass in the art of war.

The spring of 1862 found the Confederacy in a precarious position. Union General George B. McClellan’s massive Army of the Potomac, numbering over 100,000 men, was slowly but surely advancing up the Virginia Peninsula, threatening Richmond. To relieve this pressure, Confederate General Robert E. Lee, then a military advisor to President Jefferson Davis, understood that a diversion was desperately needed. His gaze turned to the Shenandoah Valley, a fertile crescent of agricultural bounty and a critical strategic corridor. It was here that Jackson, an enigmatic and intensely religious former VMI professor, commanded a small, isolated force. Lee’s instructions to Jackson were clear: "The enemy must be disquieted and deceived as to our numbers and designs." Jackson, a man of profound faith and unsettling intensity, was about to deliver far more than disquiet.

The Chessboard of the Valley: Strategic Imperatives

The Shenandoah Valley was more than just a breadbasket; it was a natural invasion route, running southwest to northeast, directly into the heart of Union territory, or providing a flanking route for Confederate forces moving east. For the Union, controlling the Valley meant protecting Washington D.C. and denying the Confederacy vital resources. For the Confederacy, holding it meant safeguarding their own territory and threatening the Union capital, thereby tying up Federal troops.

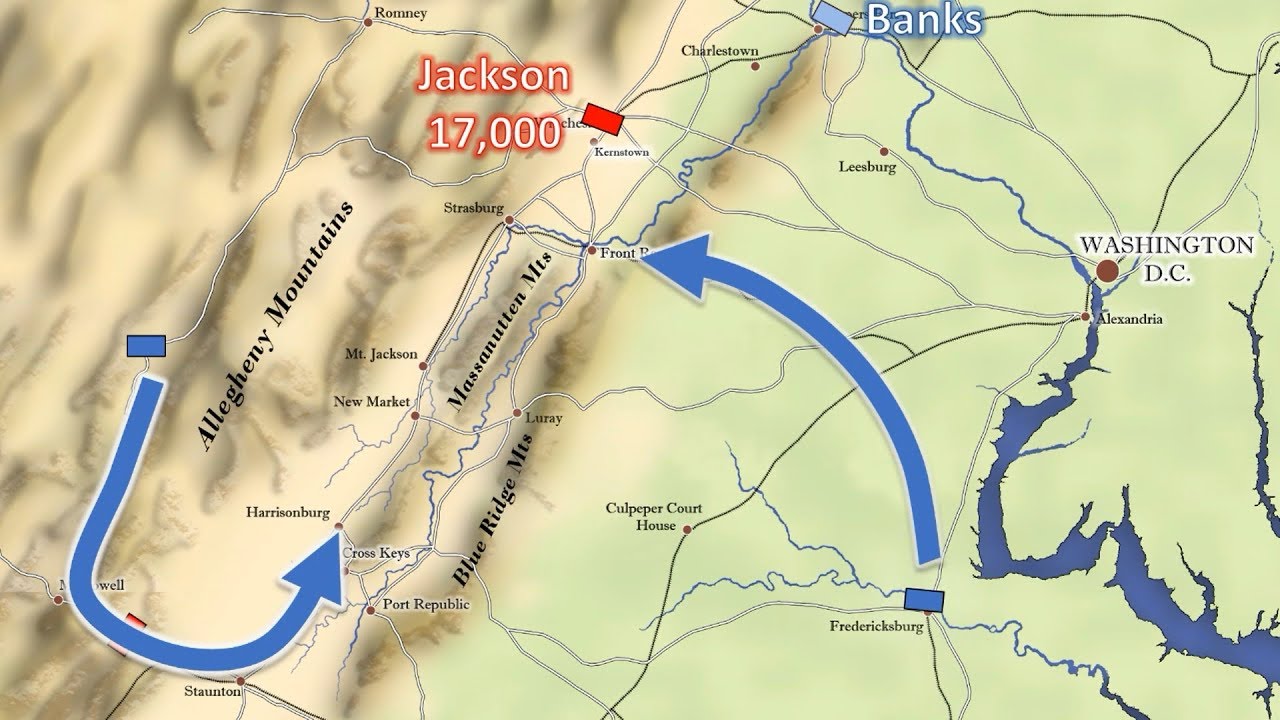

At the outset, the Union forces in the Valley were fragmented, commanded by three generals: Major General Nathaniel P. Banks (approximately 19,000 men) near Winchester, Major General John C. Frémont (around 15,000 men) further west in the Allegheny Mountains, and Brigadier General James Shields (about 11,000 men) under Banks, but soon to operate independently. Jackson’s genius lay in his ability to exploit this fragmentation, never allowing these larger forces to unite against him. His strategy was simple in concept, brutal in execution: move rapidly, strike decisively at isolated enemy elements, and keep the Union commanders guessing.

The Opening Gambit: Kernstown (March 23, 1862)

Jackson’s campaign began with a calculated risk. On March 23, believing he faced only a small Union detachment, he attacked Shields’ division near Kernstown. It was a tactical defeat for Jackson, his only loss during the entire campaign, as he was severely outnumbered. However, it was a profound strategic victory. The aggressive move convinced Union high command that Jackson was a genuine threat, prompting them to halt the movement of Banks’s corps towards McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. This decision, a direct result of Kernstown, meant that 35,000 Federal troops were now fixed in the Valley, exactly as Lee and Jackson had hoped. As Jackson famously remarked, "I was never so much interested in the result of a battle as in this, for its effect as to keeping the Federal troops in the Valley."

Following Kernstown, Jackson’s troops, soon to earn the moniker "Jackson’s Foot Cavalry," began their legendary marches. Jackson understood that speed was his greatest weapon. He drove his men relentlessly, often covering 25-30 miles a day, a pace that was unheard of in 19th-century warfare. He moved like a phantom, appearing where he was least expected, then vanishing into the rugged terrain. His men, though exhausted, developed an almost fanatical devotion to their eccentric commander, who often led from the front, a single lemon in hand, silently observing the unfolding chaos.

The Whirlwind Begins: McDowell, Front Royal, and Winchester

By early May, the Union commanders were growing frustrated. Jackson, after retreating southwest up the Valley, seemed to disappear. But he was merely preparing his next move. On May 8, he struck Frémont’s forces at the Battle of McDowell. While not a decisive victory, Jackson successfully repelled Frémont’s advance and forced him to retreat back over the Allegheny Mountains, effectively taking one Union army out of the immediate picture.

Jackson then turned his attention to Banks, who had divided his forces. Banks himself was at Strasburg, while a smaller detachment was at Front Royal. Seeing his opportunity, Jackson feinted towards Strasburg, drawing Banks’s attention, then on May 23, he executed a brilliant flanking maneuver, falling upon the unsuspecting Union garrison at Front Royal. The Confederates overwhelmed the defenders, capturing much-needed supplies and positioning themselves to cut off Banks’s retreat from Strasburg.

Banks, realizing the trap closing around him, ordered a hasty retreat down the Valley towards Winchester. What followed was a desperate race, with Jackson’s "Foot Cavalry" in hot pursuit. On May 25, Jackson’s men caught Banks’s retreating columns at Winchester. The ensuing battle was a rout. Banks’s forces were scattered and bewildered, suffering heavy casualties and losing vast amounts of supplies. The Confederates captured immense quantities of stores – food, medicine, weapons, and ammunition – that were vital for their campaign. Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was apoplectic, famously declaring, "The Valley is open!" Washington D.C. was thrown into a panic, fearing Jackson might be marching on the capital itself.

Washington’s Panic and Jackson’s Escape

The Union response to Jackson’s successes was immediate and overwhelming. President Lincoln, diverting troops intended for McClellan, ordered a massive convergence on the Valley. Three Union armies, commanded by Frémont, Shields, and Banks, now totaling over 60,000 men, were attempting to encircle Jackson and crush his smaller force. It was a desperate moment for the Confederates.

But Jackson, ever the master of deception and rapid movement, was already planning his escape. With the Union noose tightening, he began a rapid retreat up the Valley, his men once again covering astonishing distances. He led his exhausted troops, laden with captured spoils, through gaps in the Blue Ridge Mountains, aiming to keep his pursuers divided and defeat them in detail.

The Final Act: Cross Keys and Port Republic

Jackson’s strategic brilliance culminated in the twin battles of Cross Keys and Port Republic on June 8 and 9. As Frémont’s army pursued Jackson up the west side of the Shenandoah River, Shields’s army was advancing up the east side. Jackson, understanding that these two forces needed to be defeated separately before they could unite, executed a daring plan.

On June 8, at Cross Keys, Major General Richard S. Ewell’s division, under Jackson’s command, turned and decisively defeated Frémont’s attacking forces. After securing this victory, Jackson left a small detachment to hold Frémont in check and then, under the cover of darkness, rapidly moved the bulk of Ewell’s men across the swollen South Fork of the Shenandoah River to reinforce his main body, which was now facing Shields at Port Republic.

The next day, June 9, at Port Republic, Jackson launched a fierce assault against Shields’s lead elements. The battle was a desperate, back-and-forth affair, with Confederate lines nearly breaking at one point. However, with the timely arrival of Ewell’s reinforcements from Cross Keys, Jackson’s forces managed to push back Shields’s men, inflicting heavy casualties and forcing them to retreat in disorder.

With the victories at Cross Keys and Port Republic, Jackson had effectively eliminated the immediate threat from all three Union armies. He had kept them separated, defeated them sequentially, and now, with the Valley cleared, he was free to link up with Lee.

The Aftermath and Legacy

By mid-June, Jackson’s Valley Campaign was over. He had achieved every strategic objective and more. He had diverted nearly 60,000 Union troops from McClellan’s front, severely weakening the Federal threat to Richmond. His "Foot Cavalry" had marched over 600 miles, fought six significant engagements (including a minor one at Harrisonburg), captured thousands of prisoners and immense quantities of supplies, all while sustaining relatively light casualties.

The impact of the campaign was profound. For the Confederacy, it was a desperately needed shot in the arm, a morale booster that defied the odds and showcased the potential of their leadership. For the Union, it was a humiliating series of defeats that sowed confusion and frustration in Washington. Crucially, it bought Robert E. Lee the time he needed to reorganize his forces and prepare for the Seven Days Battles, which would ultimately drive McClellan away from Richmond.

Jackson’s name became synonymous with audacious brilliance. His tactics – rapid movement, surprise attacks, and concentration of force against a divided enemy – are still studied in military academies today. He understood the psychological impact of constant pressure and the demoralizing effect of uncertainty on an enemy. His deep personal faith, combined with his unwavering resolve and eccentric habits, made him an almost mythical figure to his men and a terrifying enigma to his adversaries.

The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862 stands as a testament to the power of strategic genius, tactical innovation, and the indomitable will of a determined commander. It was a campaign that shaped the course of the Civil War, solidified "Stonewall" Jackson’s place in history, and continues to inspire awe and admiration for its sheer audacity and unparalleled success. It was, quite simply, a storm of military brilliance that swept through the Valley and left an indelible mark on the landscape of American history.