Echoes of Trauma: The Silent Epidemic of Youth Suicide in Indigenous Communities

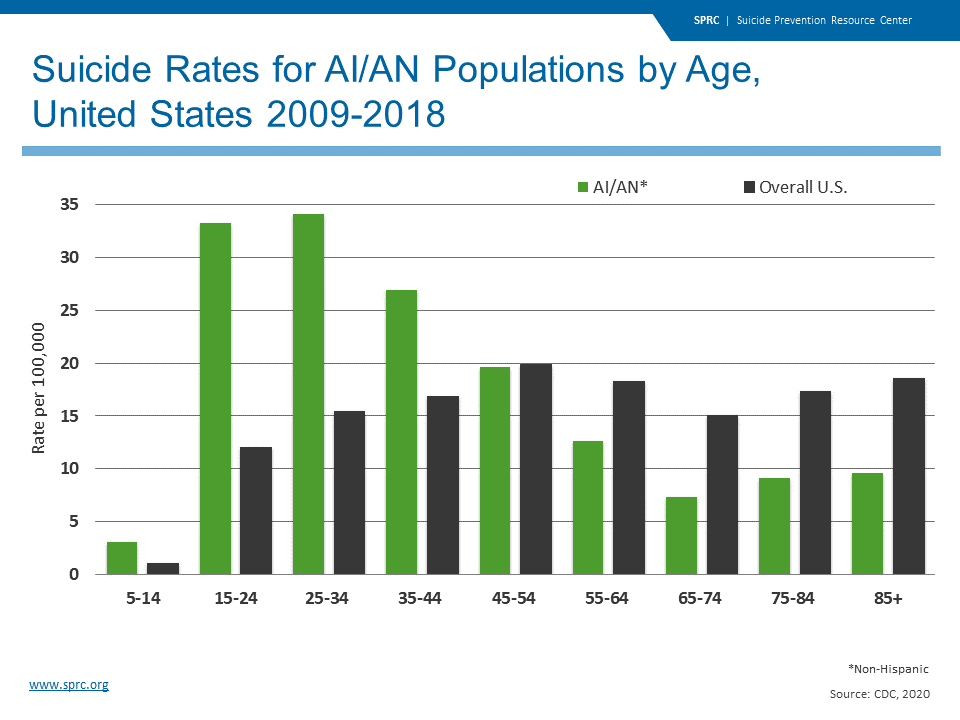

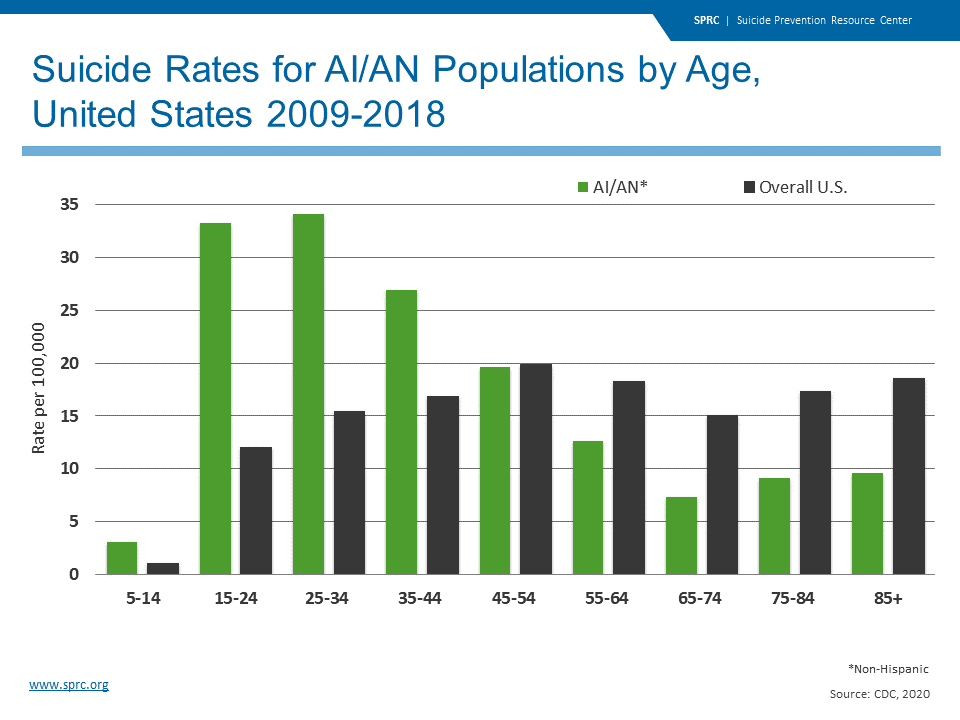

In the quiet expanse of tribal lands across the United States, a silent epidemic casts a long, chilling shadow: the alarmingly high rates of suicide among Native American teenagers. It’s a crisis often overlooked, yet it rips through families and communities with devastating force, leaving behind a trail of grief and unanswered questions. While suicide is a leading cause of death for young people nationwide, for Native American youth aged 10-24, the rate is often 2 to 3 times higher than the national average, and in some tribal communities, it can be up to 10 times higher. This stark disparity is not merely a tragic statistic; it is a profound indicator of systemic failures, historical injustices, and a deep-seated intergenerational trauma that continues to haunt Indigenous peoples.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Indian Health Service (IHS) consistently report these grim figures, painting a picture of a population segment in profound distress. For young Native American men, the suicide rate is particularly acute, soaring to rates comparable to, or even exceeding, those seen in some of the most vulnerable populations globally. These numbers represent not just lives lost, but futures extinguished—the loss of potential leaders, artists, healers, and culture keepers, each a vital thread in the intricate tapestry of their nations.

To truly grasp the magnitude and complexity of this crisis, one must delve beyond the immediate symptoms and confront the historical roots that have shaped the contemporary landscape of Indigenous health. Centuries of colonial violence, forced displacement, land theft, and the systematic dismantling of Native cultures have left an indelible mark. The most direct and devastating historical policy contributing to the current mental health crisis is arguably the federal Indian boarding school system. From the late 19th century through much of the 20th, hundreds of thousands of Native children were forcibly removed from their families and communities, sent to institutions designed to "kill the Indian to save the man."

At these boarding schools, children were forbidden to speak their languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or express their cultural identities. They endured severe physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, often without any form of loving support. This institutionalized trauma severed intergenerational bonds, disrupted traditional parenting practices, and instilled a deep sense of shame and worthlessness. Survivors, upon returning home, often struggled to reconnect with their families and communities, carrying the unhealed wounds of their experiences.

"The crisis isn’t simply about mental illness; it’s about a spiritual and cultural disconnection that stems from centuries of oppression," emphasizes Dr. Nicole A. Bowman, a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians and a leading researcher on Indigenous health disparities. "Healing must be holistic and culturally grounded, addressing not just individual symptoms but the collective soul wound."

The concept of intergenerational trauma is crucial here. Often described as a "soul wound," it explains how the unaddressed trauma of past generations can manifest in the present, impacting mental health, parenting styles, and community well-being. The trauma of boarding schools, massacres, and forced removals does not simply disappear; it can be passed down through epigenetic changes, family narratives, and societal structures. This manifests as higher rates of substance abuse, domestic violence, depression, anxiety, and, tragically, suicide among descendants, even those who never directly experienced the initial trauma.

Beyond historical trauma, contemporary socioeconomic factors perpetuate the cycle of despair. Many tribal communities grapple with chronic underfunding, leading to inadequate housing, limited access to nutritious food, and a severe lack of educational and employment opportunities. Poverty rates on reservations are significantly higher than the national average, creating environments of chronic stress and limited prospects. This economic marginalization often translates into poor access to quality healthcare, including mental health services.

The existing mental healthcare infrastructure in many tribal communities is woefully insufficient. There is a severe shortage of culturally competent mental health professionals who understand the unique historical context and cultural nuances of Indigenous peoples. Services are often geographically distant, requiring long travel times and posing logistical barriers for families without reliable transportation. Even when services exist, stigma surrounding mental illness can deter individuals from seeking help, particularly in close-knit communities where privacy is scarce. The Western model of therapy, often focused on individual pathology, can also clash with Indigenous holistic worldviews that emphasize community, spirituality, and balance.

The erosion of cultural identity, a direct consequence of historical policies, leaves many young people feeling disconnected from their heritage and unsure of their place in the world. When traditional languages, ceremonies, and knowledge systems are suppressed, a vital source of resilience, meaning, and belonging is lost. This cultural void can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and alienation, making young people more vulnerable to negative coping mechanisms like substance abuse, which itself is a major risk factor for suicide.

"We’re losing our future," states Chief Ben Carter of the fictional "Eagle Creek Nation," echoing sentiments heard across real tribal lands. "Every young person we lose is a library burned, a song silenced. We need resources, yes, but we also need our traditions back, strong and vibrant, to remind our children of who they are and the strength they carry."

The journey towards healing is complex and multifaceted, requiring a comprehensive approach that addresses historical injustices, socioeconomic disparities, and mental health system failures. Yet, amidst the despair, stories of resilience and profound hope emerge from Indigenous communities determined to reclaim their narratives and protect their youth.

Many tribal nations are leading the charge in developing culturally relevant prevention programs. These initiatives often incorporate traditional healing practices, ceremonies, and elder mentorship, which provide a sense of belonging, purpose, and cultural pride. Language immersion programs are being revitalized, connecting young people to their ancestral tongues, which are seen not just as communication tools but as vessels of worldview and identity. Youth empowerment programs focus on leadership development, cultural arts, and community engagement, offering alternatives to despair and fostering a sense of agency.

Elder Mary Cloud, a traditional healer from a Lakota community, observes, "Our young people are hurting because they carry the pain of their ancestors. But they also carry the strength. Our ceremonies, our language, our stories – these are the medicines they need to remember who they are, to feel connected to something bigger than themselves, and to find their path forward."

Successful prevention strategies are often community-led and emphasize a holistic approach to well-being, recognizing that mental health is intrinsically linked to spiritual, physical, and emotional health, as well as connection to land and community. These programs often include:

- Culturally Specific Mental Health Services: Integrating traditional healers and practices with Western therapy, offering services in Native languages, and training culturally competent providers.

- Youth Engagement and Leadership: Creating safe spaces for youth to express themselves, develop leadership skills, and participate in cultural activities.

- Strengthening Family and Community Bonds: Programs that support healthy parenting, foster intergenerational connections, and build strong social networks.

- Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Advocating for increased funding for housing, education, economic development, and healthcare infrastructure in tribal communities.

- Historical Trauma Informed Care: Educating service providers and community members about the impacts of historical trauma and incorporating this understanding into all interventions.

Addressing this crisis requires not just increased funding for organizations like the Indian Health Service, but a fundamental shift in policy that respects tribal sovereignty and self-determination. It means supporting Indigenous-led solutions, investing in cultural revitalization, and actively working to dismantle the systemic racism and discrimination that continue to impact Native lives. It also means acknowledging the historical injustices that underpin this crisis and engaging in truth and reconciliation efforts.

The silent epidemic of youth suicide in Native American communities is a profound call to action. It demands attention, resources, and a deep commitment to healing. The path forward is long, but it is paved with the unwavering spirit of a people determined not just to survive, but to thrive, carrying the wisdom of their ancestors into a healthier future where every young life is cherished, protected, and given the opportunity to flourish. The silence surrounding this epidemic must be broken, replaced by understanding, empathy, and effective action that honors the resilience and inherent strength of Indigenous nations.