Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article about the Sultana Mine, Nevada, using it as a lens to explore the broader boom and bust of the Bullfrog Mining District, particularly Rhyolite.

The Ghost of Gold: Unearthing the Silent Ambitions of Nevada’s Sultana Mine

RHYOLITE, NEVADA – Under the relentless, unblinking eye of the Mojave sun, a landscape of raw, formidable beauty unfolds. Here, in the heart of Nevada’s stark, sun-baked desert, lie the skeletal remains of dreams once as bright and shimmering as the gold they sought. Among the countless scars etched into the earth – abandoned shafts, crumbling adits, and silent tailings piles – stands the story of the Sultana Mine, a name that, while perhaps not as famous as the district’s most prolific producers, embodies the fervent hope, the dizzying speculation, and the ultimate, poignant collapse of the Bullfrog Mining District.

The Sultana, nestled within a few miles of the now-iconic ghost town of Rhyolite, was not merely a hole in the ground; it was a testament to the insatiable human desire for instant wealth, a silent monument to the thousands who flocked to this desolate corner of the American West at the dawn of the 20th century. Its narrative, woven into the fabric of Rhyolite’s meteoric rise and fall, offers a vivid snapshot of an era when the desert whispered promises of untold riches, and men were willing to risk everything to claim them.

The Golden Whisper: A District Awakens

The story of the Bullfrog District, and by extension, the Sultana Mine, begins in August 1904. It was then that two prospectors, Frank "Shorty" Harris and Ed Cross, stumbled upon outcroppings of quartz veined with free gold near what would become the town of Beatty. The discovery was not just significant; it was spectacular. The gold, they said, was so rich that it resembled the green skin of a frog, giving the district its whimsical, yet utterly serious, name.

News traveled like wildfire across the parched landscape. Already reeling from previous strikes in Tonopah and Goldfield, Nevada, the West was primed for another gold rush. Within months, a trickle of hopefuls became a torrent. By 1905, the dusty valleys around the Bullfrog were teeming with prospectors, speculators, and entrepreneurs, all eager to stake their claim in what they believed was the next great bonanza.

"Every man who came here carried a pickaxe in one hand and a dream in the other," recounts Dr. Evelyn Reed, a historian specializing in Nevada’s mining boom-and-bust cycles. "They weren’t just seeking gold; they were seeking a new life, a chance to escape the mundane, to become a legend overnight. The Bullfrog District, for a brief, glorious period, felt like the epicenter of that possibility."

Rhyolite’s Roar: A City of Dust and Dreams

The most spectacular manifestation of this feverish ambition was the birth and explosive growth of Rhyolite. Located about four miles west of Beatty, Rhyolite sprang from the desert floor with breathtaking speed. By 1907, just three years after Shorty Harris’s discovery, Rhyolite was a thriving metropolis, boasting a population estimated at anywhere from 3,500 to 5,000, though some accounts pushed it closer to 10,000 during peak periods.

This wasn’t just a ramshackle camp; it was a burgeoning city, complete with three banks, a stock exchange, a hospital, a school, an opera house, and a staggering 50 saloons. Electricity, telegraph lines, and even a daily newspaper, the Rhyolite Herald, kept its residents connected and informed. Three separate railroad lines—the Las Vegas and Tonopah, the Tonopah and Tidewater, and the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad—raced to connect Rhyolite to the outside world, ferrying in supplies, machinery, and, crucially, more investors.

It was in this crucible of intense activity and boundless optimism that the Sultana Mine found its footing. Like dozens of other claims in the Bullfrog District, the Sultana was one of the many promising prospects that drew the eye of eager investors. While not achieving the colossal output of some of its neighbors like the Montgomery Shoshone or the Pioneer, the Sultana was frequently mentioned in local mining reports, its assays often showing encouraging values, its stock traded on the bustling Rhyolite exchange.

The Sultana’s Promise: A Speculator’s Delight

The Sultana Mine represented the quintessential speculative venture of the era. Initial reports and assays from various mines in the district, including the Sultana, were often promising, sometimes incredibly so. Samples of ore from the Bullfrog District were known to contain gold values reaching into the hundreds, even thousands, of dollars per ton – figures that would make any prospector’s heart race.

"The allure wasn’t just the gold in the ground; it was the story you could tell about it," explains Dr. Reed. "A mine like the Sultana might not have had a massive ore body, but it had enough promising assays, enough ‘showings,’ to attract capital. Investors, many of whom had never seen a mine in their lives, poured money into these ventures, fueled by the excitement generated in the stock markets of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and even New York."

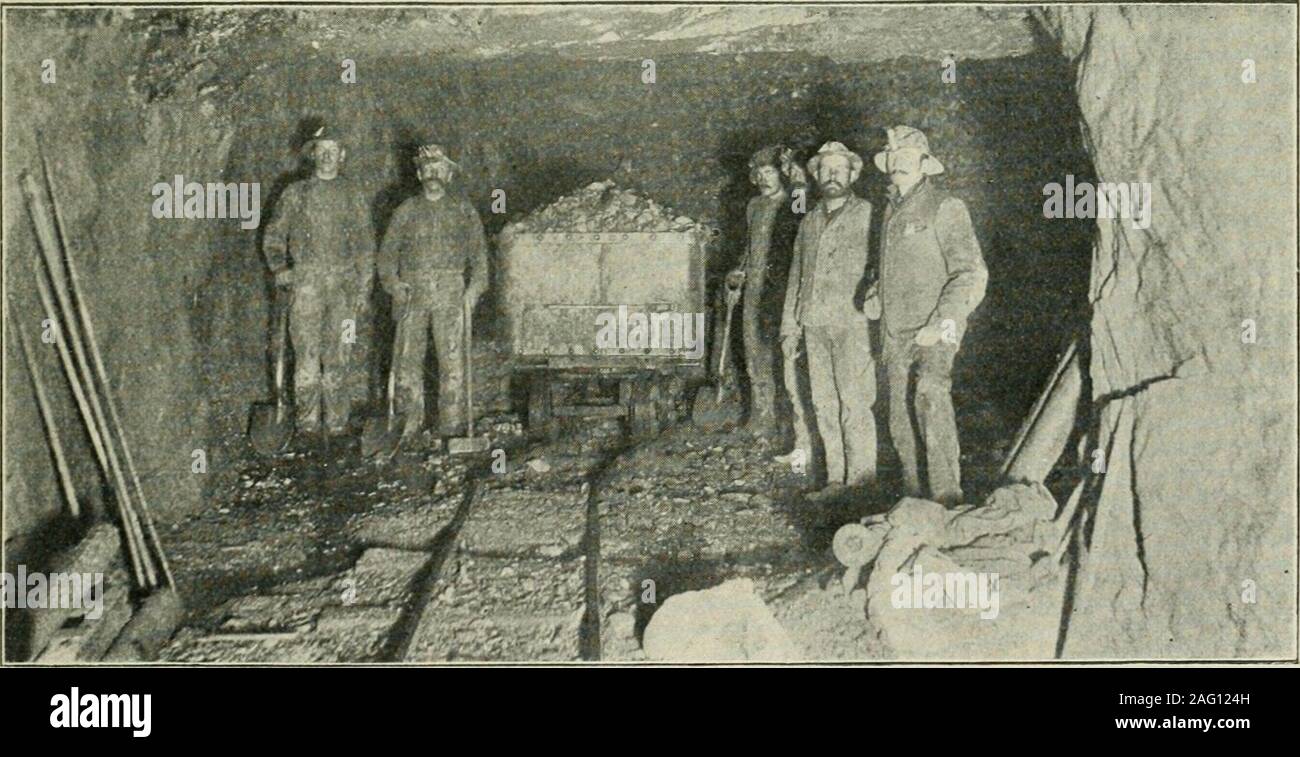

The Sultana, like many others, had its share of development. Shafts were sunk, drifts extended, and modest headframes erected. Miners toiled in the stifling heat, drilling and blasting, their hopes riding on every shovelful of rock. Life at the Sultana, as at all the district’s mines, was brutal. Water was scarce and expensive, sometimes costing more than $1 a gallon. Supplies had to be hauled across vast stretches of desert. Temperatures soared in summer and plummeted in winter. Yet, the promise of gold was a potent antidote to hardship.

The Sands of Time: When the Bubble Burst

But beneath the glittering surface of Rhyolite’s prosperity and the Sultana’s potential, cracks began to appear. The very factors that had fueled the boom – rapid development, intense speculation, and sometimes exaggerated reports – also sowed the seeds of its destruction.

The ore, while rich in places, proved to be far more sporadic and less consistent than initially hoped. Many claims, including some that had seen significant investment, simply didn’t pan out. The cost of extracting and milling the ore in such a remote and harsh environment was exorbitant. Fraudulent claims and "salted" samples also played their part, further eroding investor confidence.

The final, devastating blow came in the form of the Panic of 1907. A severe financial crisis that gripped the United States, it caused a sharp contraction in credit and a widespread loss of investor confidence. Money, which had flowed so freely into speculative ventures like those in the Bullfrog District, suddenly dried up. Banks failed, stock markets crashed, and the capital essential for mining operations vanished almost overnight.

"The Panic of 1907 was a death knell for many mines, the Sultana included," says Dr. Reed. "When the money stopped, the picks stopped. There was no capital for further exploration, no funds for new machinery, and no market for the ore that was being extracted. It was a domino effect that toppled the entire district."

Rhyolite’s Retreat: The Wind’s New Tenant

As quickly as it had risen, Rhyolite began its precipitous decline. Mines like the Sultana, unable to secure funding or prove consistent profitability, were abandoned. Workers left, followed by merchants, bankers, and doctors. By 1910, the population had dwindled to a few hundred. The grand buildings, once symbols of ambition, were stripped of their valuable materials – windows, doors, and lumber – to be repurposed in other, more enduring towns. The train tracks, which had once brought life, were eventually torn up.

By 1920, Rhyolite was virtually a ghost town, its once-bustling streets now silent, its buildings reduced to skeletal frames against the vast desert sky. The wind became its primary resident, whistling through empty doorways and rattling loose corrugated iron.

The Sultana Today: Echoes in the Silence

Today, the Sultana Mine, like scores of others in the Bullfrog District, stands as a silent sentinel to that bygone era. Its exact location might be known only to dedicated historians or intrepid prospectors, but its story is universal. It represents the thousands of similar ventures across the American West that were born of hope, nurtured by speculation, and ultimately consumed by the harsh realities of geology and economics.

Visitors to Rhyolite today are drawn to its evocative ruins: the Bottle House, constructed from thousands of discarded glass bottles; the ghostly facade of the Cook Bank building; the remains of the train depot. These structures are not merely crumbling stone and timber; they are tangible links to a time when men believed they could tame the desert and strike it rich.

The Sultana Mine, though less visually dramatic than Rhyolite’s main street, is an integral part of this narrative. Its abandoned shafts and scattered debris are a powerful reminder that for every success story of the gold rush, there were hundreds, if not thousands, of endeavors like the Sultana – mines that promised much, delivered little, but whose very existence fueled the dreams of an entire generation.

The desert, with its profound silence and enduring beauty, now holds these stories close. The Sultana Mine, forever etched into the landscape, continues to whisper tales of ambition, of fortune sought and lost, and of the enduring, sometimes tragic, allure of gold in the American West. It stands not as a monument to a rich strike, but as a poignant memorial to the human spirit’s boundless capacity for hope, even in the most unforgiving of lands.