Okay, here is a 1200-word article in English about the Taos, New Mexico revolt, framed within the broader context of American legends, written in a journalistic style.

The Whispering Adobe: Taos and the Fiery Birth of an American Legend

Beneath the azure skies of northern New Mexico, where the Sangre de Cristo Mountains meet the ancient earth, lies Taos – a place steeped in a beauty so profound it feels almost mystical. Its adobe walls, sculpted by centuries of sun and wind, seem to whisper tales of resilience, of cultural fusion, and of a past that refuses to be forgotten. Yet, among the galleries and tranquil plazas, lies a powerful, often unsettling, American legend: the Taos Revolt of 1847. This isn’t a legend of cowboys and outlaws, but one of conquest and resistance, a stark reminder that the American narrative is far more complex and blood-soaked than many popular myths suggest.

The Taos Revolt is a pivotal, yet frequently overlooked, chapter in the unfolding story of the American West. It’s a legend not in the fantastical sense, but in its enduring power to shape identity, inspire historical inquiry, and reveal the violent seams where cultures clashed as the United States expanded its borders. It speaks to the heart of what it means to be American, born from a crucible of competing claims and desperate struggles.

The Uninvited Guest: America Arrives in New Mexico

To understand the Taos Revolt, one must first grasp the dramatic geopolitical shift that preceded it. For centuries, New Mexico had been a remote, self-sufficient, and culturally rich outpost, first of the Spanish Empire and, after 1821, of independent Mexico. Its people – the indigenous Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache, alongside the Hispano descendants of Spanish colonists – had forged a unique way of life, distinct from both Mexico City and the burgeoning United States.

Then came the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). In the summer of 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny, leading his "Army of the West," marched into Santa Fe and, without firing a shot, declared New Mexico a territory of the United States. His proclamation, issued from the Governor’s Palace, was a promise and a warning: "Americans now govern New Mexico, and we will protect you in your persons, your property, and your religion." On the surface, it seemed a bloodless conquest, an easy acquisition. But beneath the veneer of peaceful transition, resentment simmered.

The American occupation was, for many New Mexicans, an uninvited imposition. New customs, new laws, and new officials quickly replaced the familiar. Land titles, always a contentious issue, became even more precarious under a foreign legal system. New taxes were levied, often by officials perceived as arrogant and dismissive of local traditions. The Anglo newcomers, many of whom harbored deep prejudices against both the Hispano and indigenous populations, often viewed the established culture as backward and uncivilized.

A Powder Keg in the Northern Frontier

Nowhere were these tensions more acutely felt than in the northern frontier settlements, particularly Taos. Taos was a vibrant hub, a nexus of trade, culture, and intermarriage between Pueblo, Hispano, and a smattering of Anglo residents. It was also a place where the American presence felt particularly intrusive. The new American governor, Charles Bent, a prominent American trader who had lived in Taos for years and married a local woman, seemed to embody this complex transition. His appointment was meant to bridge the gap, but instead, it placed him at the heart of the storm.

Local leaders, both Pueblo and Hispano, watched with growing alarm. Among them was Padre Antonio José Martínez, the charismatic and controversial priest of Taos. A towering figure in New Mexican history, Martínez was a complex character: a defender of his people against Anglo incursions, an advocate for education and land reform, yet also accused by some of secretly fanning the flames of rebellion. His sermons and writings, often critical of the new regime, resonated deeply with a populace feeling increasingly disenfranchised.

The spark that ignited the powder keg was a combination of fear and perceived injustice. Rumors circulated of American plans to seize land, to impose even heavier taxes, and to suppress local religion and customs. For the Pueblo people, whose ancestors had resisted Spanish attempts at cultural erasure in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the threat was particularly chilling. For the Hispanos, their newfound Mexican identity was being abruptly replaced by an alien American one.

The Bloody Morning of January 19, 1847

The simmering discontent exploded into open rebellion on January 19, 1847. A coalition of Pueblo and Hispano insurgents, fueled by anger and a desperate desire to reclaim their sovereignty, launched a coordinated attack. Governor Bent, who had traveled from Santa Fe to his home in Taos, became their primary target.

The rebels stormed Bent’s house. What followed was brutal. Bent, attempting to escape, was shot with arrows and scalped while his wife, Ignacia Jaramillo, and children bravely tried to hide him. His death was a stark symbol of the revolt’s ferocity and the depth of the people’s fury.

The violence did not stop with Bent. Other American officials and their supporters in Taos and surrounding communities were also murdered, including the circuit attorney, the sheriff, and the prefect. The message was unmistakable: the people of northern New Mexico rejected American rule. The uprising quickly spread, with rebels seizing control of the region, their numbers swelling as they marched towards Santa Fe.

The Iron Fist of Retribution

The American response was swift and merciless. Colonel Sterling Price, commander of the U.S. forces in New Mexico, immediately mobilized his troops. He understood that if the revolt was not crushed decisively, it could unravel the entire American occupation of the Southwest.

On February 4, Price’s forces, augmented by local volunteers loyal to the American cause, engaged the rebels in a fierce battle at the village of Embudo. Though outnumbered, the superior firepower and training of the American soldiers proved decisive. The rebels were forced to retreat, falling back to the Taos Pueblo, an ancient, multi-storied adobe complex that had served as a fortress for centuries.

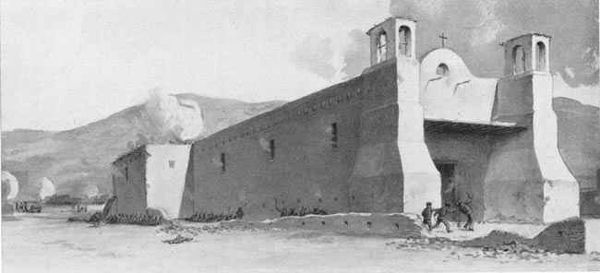

The stage was set for the revolt’s tragic climax. The rebels, along with many women and children, sought refuge within the thick walls of the Taos Pueblo church, San Geronimo. On February 4, 1847, Colonel Price laid siege to the Pueblo. His artillery hammered the adobe walls of the church, turning the sacred sanctuary into a death trap. Eyewitness accounts speak of the horrific scene: "The artillery was brought to bear upon the church, and after a cannonade of two hours, a breach was effected, through which the troops entered and engaged the enemy in a hand-to-hand fight."

The battle within the church was a massacre. Hundreds of rebels were killed, many trapped inside the collapsing structure. Those who tried to flee were cut down by musket fire. The American victory was absolute, but the cost in human lives was staggering.

The Aftermath: Trials and Executions

In the wake of the military defeat, American justice, or what passed for it, arrived. Summary trials were held, often with little regard for due process. Men accused of participating in the revolt were quickly condemned. Many were hanged, some publicly, as a chilling warning to any who might consider further resistance.

One particularly poignant anecdote from these trials is attributed to Judge Joab Houghton, who reportedly told one condemned man: "The court has no mercy for you, and your only hope is in the mercy of God, and I advise you to make good use of the short time that is left you to prepare for eternity." This chilling declaration underscored the punitive nature of the American response and the absolute power now wielded by the new government.

Padre Martínez, despite his outspoken criticisms, was never formally implicated in the direct planning of the revolt, though his role remains a subject of historical debate. He continued to serve his community, a testament to his complex legacy.

A Legend Etched in Adobe and Memory

The Taos Revolt of 1847, though brutally suppressed, did not disappear from the collective memory. Instead, it transformed into a legend, a whispered narrative passed down through generations. It is a legend of:

- Resistance Against Conquest: It stands as a powerful symbol of a people fighting for their land, their culture, and their very identity against an invading force. It challenges the sanitized "manifest destiny" narrative, revealing the violent cost of westward expansion.

- Cultural Clash and Misunderstanding: The revolt epitomizes the profound chasm between Anglo-American culture and the deeply rooted Hispano and Pueblo ways of life. It highlights the arrogance of conquest and the tragedy of cultures unable or unwilling to bridge their differences.

- The Complexities of Identity: For New Mexicans, the revolt forced a wrenching choice of allegiance. It forever shaped their unique identity, a blend of indigenous, Spanish, Mexican, and ultimately, American influences, often forged in conflict.

- A Hidden History: For many years, the Taos Revolt was largely ignored or downplayed in mainstream American history, deemed an inconvenient truth that didn’t fit the heroic narrative of expansion. But like many "lost" chapters, its legend grew, kept alive in local lore and academic inquiry, demanding its rightful place in the national story.

Today, Taos Pueblo remains a UNESCO World Heritage site, its ancient walls standing as silent witnesses to millennia of human history, including the bloody events of 1847. The Taos Historic Museums preserve structures like the Governor Bent House, allowing visitors to glimpse the sites of both domesticity and violence.

The legend of the Taos Revolt serves as a vital counter-narrative to the simpler, more triumphant tales of American history. It reminds us that the nation was not built without resistance, without sacrifice, and without the profound suffering of those who found themselves on the wrong side of manifest destiny. It’s a legend that asks us to look beyond the picturesque adobe, to listen to the whispers of the past, and to confront the uncomfortable truths that forged the complex tapestry of America. In doing so, we don’t just learn history; we understand the legends that continue to define us.