The Apache Wars: A Century of Defiance in the American Southwest

The vast, sun-scorched landscapes of the American Southwest hold countless stories etched into their canyons and mesas. Among the most enduring and tragic are those of the Apache Wars, a protracted and brutal struggle that pitted a resilient indigenous people against the encroaching forces of two nations for over a century. More than just a series of battles, these wars represent a profound clash of cultures, a testament to indomitable spirit, and a grim chapter in the expansion of the United States.

From the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century to the final surrender of Geronimo in 1886, the Apache – or Nde, as many bands called themselves – fought fiercely to preserve their way of life, their lands, and their freedom. Their resistance was not born of inherent belligerence, but of a fierce determination to defend their ancestral territories and a deep-seated suspicion of outsiders who consistently broke promises and encroached upon their existence.

The Genesis of Conflict: From Spanish to American Hegemony

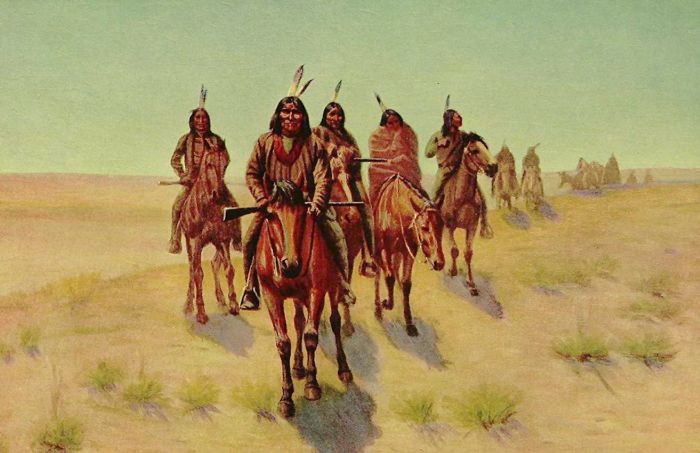

The Apache, composed of numerous independent bands like the Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, and Western Apache, were semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers and formidable raiders. For centuries, they had successfully navigated and dominated a vast territory spanning parts of present-day Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and northern Mexico. Their initial interactions with Europeans were with the Spanish, who found them a formidable foe, often referring to them as "Apaches de guerra" (war Apaches). The Spanish policy of "peace by purchase" – offering goods in exchange for peace – often proved temporary, leading to cycles of raid and reprisal.

When Mexico gained independence in 1821, the new government inherited the Apache "problem" but lacked the resources and will to maintain the previous Spanish peace agreements. This led to an intensification of conflict, with both sides committing atrocities. However, the true catalyst for the prolonged Apache Wars, as understood in American history, was the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. This treaty, ending the Mexican-American War, transferred vast territories, including Apache lands, to the United States. Suddenly, the Apache found themselves dealing with a new, rapidly expanding power that had little understanding of their culture or their deep connection to the land.

The Spark Ignites: Mangas Coloradas and the Bascom Affair

The early years of American presence were marked by uneasy co-existence, often punctuated by violence. Gold discoveries in Arizona and New Mexico brought a flood of miners and settlers, directly infringing upon Apache hunting grounds and water sources. A pivotal moment, often cited as the ignition point for decades of full-scale warfare, was the Bascom Affair of 1861.

Cochise, a respected leader of the Chiricahua Apache, and his family were falsely accused by a young U.S. Army officer, Lt. George Bascom, of kidnapping a local rancher’s son. Despite Cochise’s fervent denials and offers to help find the boy, Bascom, fueled by inexperience and a lack of understanding, ordered his arrest. Cochise managed to escape, but several of his relatives, including his brother and nephews, were held hostage. In retaliation, Cochise seized several Americans. The ensuing standoff ended in tragedy: Bascom hanged Cochise’s relatives, and Cochise, in turn, executed his American captives. This act of profound misunderstanding and injustice shattered any hope of peaceful co-existence with the Chiricahua.

"The Bascom Affair," historian Dan L. Thrapp wrote, "was one of the most tragic and stupid blunders in the history of the Indian Wars." It transformed Cochise, who had previously been open to negotiation, into a implacable enemy. He allied with his father-in-law, the equally powerful and respected Mimbres Apache chief, Mangas Coloradas. Mangas Coloradas, whose name meant "Red Sleeves," was a towering figure, both physically and politically, and had long advocated for armed resistance against the encroaching whites. Together, these two leaders launched a devastating campaign of guerrilla warfare, paralyzing travel and mining operations across the region.

The death of Mangas Coloradas in 1863 was another act of betrayal that fueled Apache hatred. Invited to a peace parley under a flag of truce, he was captured by California Volunteers, tortured, and brutally murdered. His scalp was reportedly boiled and kept as a trophy. This act, coming after the Bascom Affair, cemented the Apache’s deep distrust of American intentions.

Cochise’s War and the Quest for Peace

Following Mangas Coloradas’s death, Cochise continued his war of attrition for another decade, proving himself a military genius in the rugged terrain he knew intimately. His small bands of warriors outmaneuvered and outfought larger, better-equipped U.S. Army forces. The Army, hampered by its rigid tactics and lack of knowledge of the terrain, struggled to contain the elusive Apache.

It was in this period that a remarkable and unlikely friendship blossomed between Cochise and a white man named Tom Jeffords. Jeffords, a stagecoach superintendent, sought to negotiate directly with Cochise after conventional military efforts failed. He rode alone into Cochise’s camp, an act of immense bravery, and over time, earned the chief’s respect and trust. Cochise, weary of war and yearning for peace for his people, agreed to a peace treaty in 1872, brokered by Jeffords and General Oliver O. Howard. The Chiricahua were granted a large reservation in their traditional homeland, with Jeffords appointed as their agent. This period, though brief, represented a rare moment of genuine peace and mutual respect. Cochise died in 1874, reportedly telling Jeffords, "I am going to die, my friend. We shall never see each other again."

The Reservation Era and Renewed Outbreaks

The peace was short-lived. Following Cochise’s death, the U.S. government, driven by land hunger and a "concentration policy" aimed at consolidating all Apache bands onto a single, often desolate reservation, began to dismantle the Chiricahua reservation. The infamous San Carlos Reservation in Arizona became a central point of contention. Described as "Hell on Earth" by many, it was a barren, disease-ridden place, far from traditional Apache hunting grounds and often overseen by corrupt or inept agents.

The forced relocation and the appalling conditions at San Carlos led to renewed outbreaks of hostilities. Many Apache leaders, including Victorio and Geronimo, repeatedly fled the reservations, preferring the harsh freedom of the desert to the indignity and suffering of confinement.

Victorio’s War: A Masterful Campaign

Victorio, a Warm Springs Apache chief, emerged as a brilliant strategist in the late 1870s. After repeated broken promises regarding his band’s right to live on their ancestral lands and forced moves to San Carlos, Victorio led his people off the reservation in 1879. What followed was one of the most remarkable campaigns in the history of the Indian Wars. For over a year, with a relatively small band of warriors, women, and children, Victorio outmaneuvered and inflicted heavy casualties on U.S. and Mexican troops across thousands of square miles of unforgiving terrain.

His tactics involved lightning-fast raids, ambushes, and masterful use of the land, demonstrating an unparalleled understanding of logistics and deception. "Victorio had no equal," remarked an Apache scout, "as a leader of a small band of warriors on the warpath." His campaign highlighted the immense challenges faced by conventional armies against highly mobile, adaptable guerrilla forces. Victorio was eventually cornered and killed by Mexican troops in October 1880 at Tres Castillos, Mexico, a devastating blow to Apache resistance.

Geronimo: The Last Apache Warrior

Perhaps the most famous figure of the Apache Wars, Geronimo (Goyaałé, "one who yawns") was not a hereditary chief but a respected spiritual leader and warrior. His personal crusade against the Mexicans began after his family was murdered in a Mexican attack. He joined various Apache chiefs, including Cochise and Victorio, in their resistance.

Geronimo’s multiple escapes from San Carlos and his subsequent raids in the 1880s became legendary. His small band, rarely exceeding 50 warriors, was pursued by thousands of U.S. and Mexican soldiers. General George Crook, known for his innovative use of Apache scouts, came close to capturing Geronimo in 1883 and again negotiated his surrender in 1886. However, Geronimo and a small group of followers bolted again, fearing for their lives.

The final pursuit of Geronimo’s band in 1886 became one of the largest military manhunts in American history. General Nelson Miles replaced Crook and deployed a staggering 5,000 soldiers – a quarter of the entire U.S. Army – along with heliograph stations for rapid communication across hundreds of miles. Despite the overwhelming odds, Geronimo’s band continued to evade capture for months, demonstrating their incredible endurance and mastery of the desert.

Finally, on September 4, 1886, near Skeleton Canyon in Arizona, Geronimo surrendered to General Miles. His poignant words, "I was a good warrior, I walked like the wind," captured the essence of his struggle. He asked to be returned to his homeland, but the promise was broken. Instead, he and his band, along with the Apache scouts who had served the U.S. Army, were sent into exile as prisoners of war, first to Florida, then Alabama, and finally to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Geronimo died in 1909, never having seen his Arizona homeland again. His surrender effectively marked the end of the Apache Wars.

Legacy and Reflection

The Apache Wars were a brutal and complex conflict, characterized by immense courage on both sides, but also by profound misunderstandings, broken treaties, and inexcusable atrocities. For the Apache, it was a fight for survival, for their land, and for their identity against an overwhelming tide of expansion. Their guerrilla tactics, mastery of the rugged terrain, and unyielding spirit made them perhaps the most feared and respected indigenous warriors on the American frontier.

The end of the wars did not bring peace and prosperity for the Apache. Instead, it ushered in an era of forced assimilation, loss of land, and cultural suppression. Generations were displaced, their traditions disrupted, and their self-sufficiency eroded. Yet, the Apache people endured. Today, their descendants live on reservations in Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, working to preserve their language, culture, and sovereignty.

The Apache Wars stand as a powerful and often painful reminder of the human cost of Manifest Destiny. They compel us to look beyond simplistic narratives of "savage Indians" versus "civilized settlers" and to appreciate the intricate tapestry of human experience, sacrifice, and resilience woven into the very fabric of the American Southwest. The echoes of Geronimo’s last stand, Cochise’s defiance, and Victorio’s brilliance still resonate in the vast, silent canyons, urging us to remember a century of defiance and the enduring spirit of the Nde.