The Architect of a Wilderness Empire: Samuel de Champlain’s Enduring Legacy

QUEBEC CITY – Stand today on the commanding heights of Cap Diamant, overlooking the majestic St. Lawrence River, and you stand in the shadow of history. Below, the narrow, winding streets of Old Quebec bustle with life, a vibrant testament to centuries of resilience. This city, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is more than just a picturesque tourist destination; it is the beating heart of French Canada, a nation forged from the sheer will and audacious vision of one man: Samuel de Champlain.

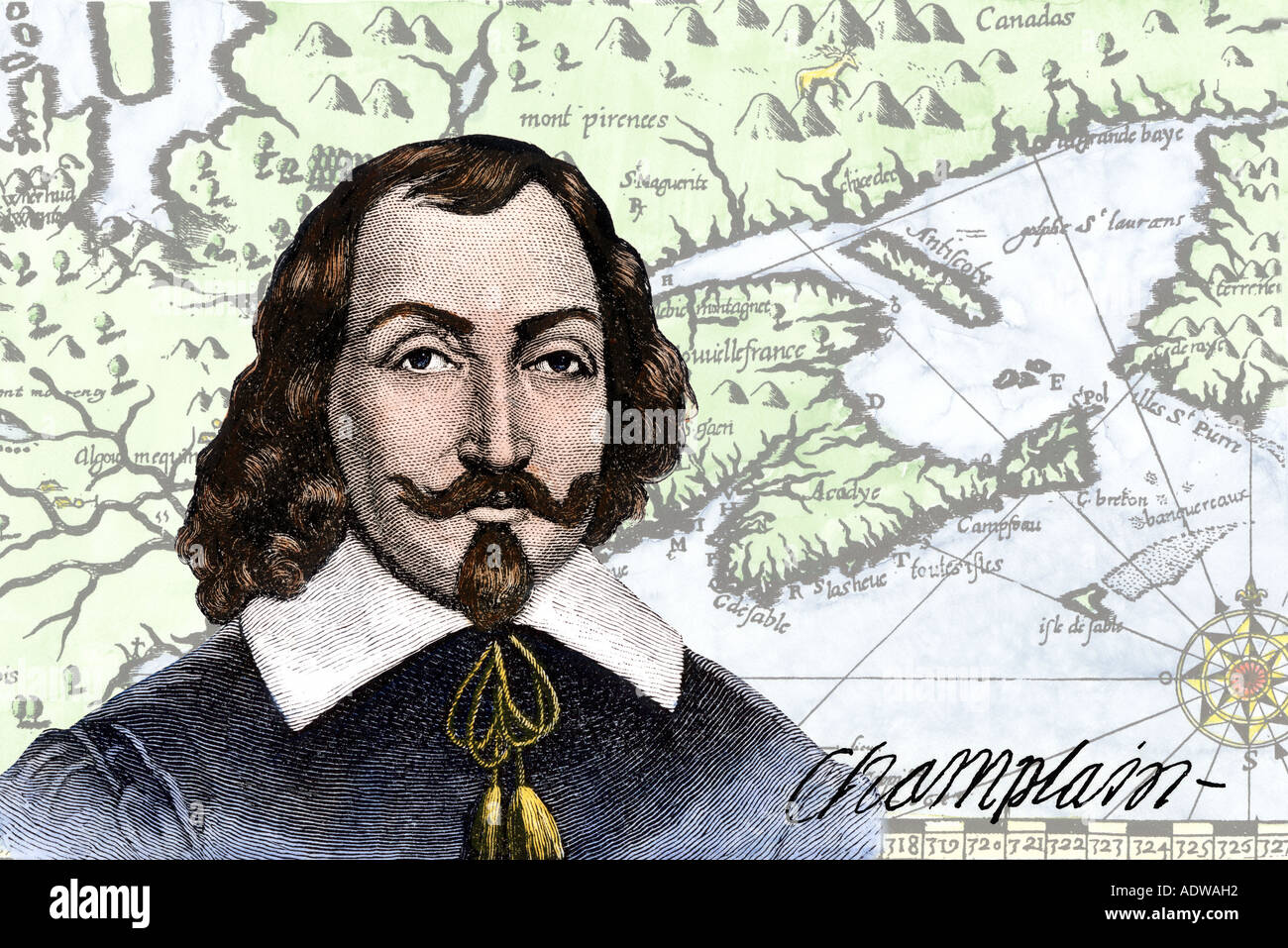

Known universally as the "Father of New France," Champlain was far more than a mere explorer. He was a cartographer, a diplomat, a military strategist, an administrator, and above all, a relentless dreamer who saw beyond the immediate profits of the fur trade to envision a permanent, thriving French colony in the vast, untamed wilderness of North America. His journey, fraught with peril, political machinations, and the unforgiving embrace of a new continent, laid the foundational stones of a civilization that endures to this day.

Born around 1574 in Brouage, a small port town on the western coast of France, Champlain’s early life remains shrouded in tantalizing mystery. While details are scarce, it’s clear he hailed from a family with strong maritime connections. He likely learned the arts of navigation and cartography from a young age, skills that would prove indispensable in his future endeavors. His experiences in the French navy, including a voyage to the West Indies and Spanish America in the late 1590s, broadened his horizons and sharpened his observational skills. His detailed report on this journey, "Brief Discours des choses plus remarquables que Samuel Champlain de Brouage a recognues aux Indes Occidentales," showcased his meticulous nature and keen eye for strategic detail, catching the attention of King Henry IV.

It was in the early 17th century, however, that Champlain truly found his calling. France, eager to stake its claim in the New World and exploit its vast resources, particularly the lucrative beaver pelts, turned its gaze westward. In 1603, Champlain embarked on his first voyage to Canada, serving under François Gravé Du Pont. He sailed deep into the St. Lawrence River, past Tadoussac, mapping and observing the land with unparalleled precision. His detailed charts and descriptions of the river, its tributaries, and the indigenous peoples inhabiting its shores were revolutionary, far surpassing anything that had come before. He understood that accurate knowledge of the geography was paramount for successful colonization.

This initial reconnaissance solidified Champlain’s conviction that the St. Lawrence offered the ideal artery for a permanent settlement. He recognized the strategic importance of a narrow point in the river, guarded by a towering cliff – a place the Algonquins called "Kebec," meaning "where the river narrows."

In 1608, under the patronage of Pierre Du Gua de Monts, Champlain returned to this strategic location with a small crew. On July 3rd, he began the construction of the "Habitation de Québec," a fortified compound that served as a storehouse, living quarters, and trading post. This was no mere seasonal camp; it was the audacious genesis of a city. The first winter was brutal, a chilling harbinger of the challenges to come. Scurvy and dysentery ravaged the small company, claiming the lives of many. Of the 28 men who arrived, only eight survived to see the spring. Yet, Champlain’s resolve remained unbroken. He wrote of the hardships with characteristic stoicism, noting, "I did not abandon my undertaking, but held it for a thing well begun."

Champlain’s brilliance extended beyond mere construction. He understood that the survival and prosperity of New France depended heavily on forging alliances with the Indigenous nations. He cultivated relationships with the Montagnais, Algonquin, and Huron peoples, recognizing their invaluable knowledge of the land, their crucial role in the fur trade, and their potential as allies against common enemies. This strategy, however, came with a heavy price.

In 1609, Champlain joined his Indigenous allies in a battle against their long-standing adversaries, the Iroquois Confederacy, near what is now Lake Champlain. Armed with the devastating power of the arquebus – a primitive firearm – Champlain and his two French companions decisively routed the Iroquois. This victory cemented the alliances with the Huron and Algonquin, but it also ignited a centuries-long enmity with the formidable Iroquois, a conflict that would profoundly shape the history of New France. It was a calculated risk, born of necessity, but its repercussions echoed through generations.

Over the next two decades, Champlain dedicated his life to nurturing his fledgling colony. He made numerous voyages back to France, tirelessly lobbying for financial support, supplies, and settlers. He published detailed accounts of his explorations and observations, including "Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France occidentale, dicte Canada," not only to inform but also to inspire further investment. He explored westward, pushing deeper into the continent, reaching Lake Huron and Lake Ontario, always in search of the elusive Northwest Passage to Asia, but also driven by a profound curiosity about the vastness of the land.

His vision for New France was holistic. He wasn’t content with just a trading post; he envisioned a self-sustaining agricultural colony, a place where French culture and Catholic faith could flourish. He encouraged the arrival of Jesuit missionaries, believing in the importance of converting the Indigenous peoples, a common European objective of the era. He also introduced European farming techniques and livestock, attempting to make the colony less dependent on precarious supply lines from France.

Life in the colony remained relentlessly challenging. Harsh winters, disease, and the constant threat of conflict tested the limits of human endurance. French support was often sporadic, as the crown’s attention was frequently diverted by European wars and internal politics. Champlain often found himself governing with limited resources, relying on his own ingenuity and leadership to maintain order and morale.

A significant setback occurred in 1629 when, amidst the Anglo-French War, English privateers under the command of the Kirke brothers captured Quebec. Champlain was taken prisoner and held in England for three years. This was a devastating blow, yet even in captivity, his spirit remained unbroken. Upon his release and the return of Quebec to French control by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1632, Champlain returned to his beloved colony with renewed vigor, determined to rebuild and strengthen it.

He served as the unofficial governor of New France, meticulously overseeing its growth and administration until his death. His deep understanding of the land, its challenges, and its peoples made him an indispensable leader. He learned several Indigenous languages and fostered a degree of mutual respect that was uncommon among European colonizers of his time, even as he pursued the French agenda.

Samuel de Champlain died in Quebec City on Christmas Day, 1635. He left behind no great personal fortune, no vast estates, but an immeasurable legacy. He had transformed a concept into a tangible reality, a wilderness outpost into the foundation of a nation. His maps, his writings, and his strategic choices provided the blueprint for future French expansion in North America.

The Canada we know today, with its rich tapestry of French and English cultures, its vibrant Quebecois identity, owes an incalculable debt to this visionary pioneer. Champlain’s enduring spirit of exploration, his unwavering perseverance in the face of adversity, and his profound commitment to his grand design continue to inspire. He built more than just a habitation on a cliff; he planted the seeds of a distinct civilization, a New France that, against all odds, would thrive and evolve, forever etching his name as its true and undeniable father. His story is a powerful reminder that sometimes, the greatest empires are not built by armies and gold, but by the relentless will and far-sighted vision of a single individual.