The Artery of Empire: How Forbes Road Forged America’s West

More than a mere path, Forbes Road was a crucible of conflict, an engineering marvel, and an artery of empire that profoundly reshaped the landscape of North America. Carved through the rugged, unforgiving wilderness of colonial Pennsylvania during the climactic years of the French and Indian War, this approximately 200-mile military highway was not just a means to an end, but an end in itself – a testament to British resolve, strategic brilliance, and the sheer grit of thousands of colonial and regular troops. Its completion in 1758 led directly to the capture of Fort Duquesne, the French stronghold at the Forks of the Ohio, and laid the foundation for what would become Pittsburgh, irrevocably altering the course of American history.

To understand the monumental significance of Forbes Road, one must first grasp the perilous geopolitical landscape of the mid-18th century. By 1755, the Ohio Country – the vast, fertile lands west of the Allegheny Mountains – had become the flashpoint of imperial rivalry between Great Britain and France. The French, asserting their claim, had established a chain of forts, including the strategically vital Fort Duquesne, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers. This audacious move threatened to sever British colonial expansion, trapping the burgeoning settlements along the Atlantic seaboard.

The British response was immediate, but disastrous. In 1755, Major General Edward Braddock, a man of rigid adherence to European military tactics, led a formidable expedition of British regulars and colonial militia to dislodge the French. His plan: to cut a direct road through the wilderness from Fort Cumberland in Maryland. However, Braddock’s arrogance and disdain for both the colonial troops and the tactics of frontier warfare proved fatal. His forces were ambushed and routed by a smaller contingent of French and Native American warriors near present-day Braddock, Pennsylvania. The defeat was a humiliating blow, shattering British prestige and leaving the frontier vulnerable to devastating raids. For three agonizing years, the Forks of the Ohio remained firmly in French hands, a constant thorn in the side of British colonial ambition.

The tide began to turn with the appointment of William Pitt the Elder as Secretary of State in 1757. Pitt, a visionary statesman, understood the global stakes of the North American conflict and committed immense resources to wrest control of the continent from France. He appointed Brigadier General John Forbes, a Scottish Highlander known for his meticulous planning and unwavering resolve, to lead a new offensive against Fort Duquesne.

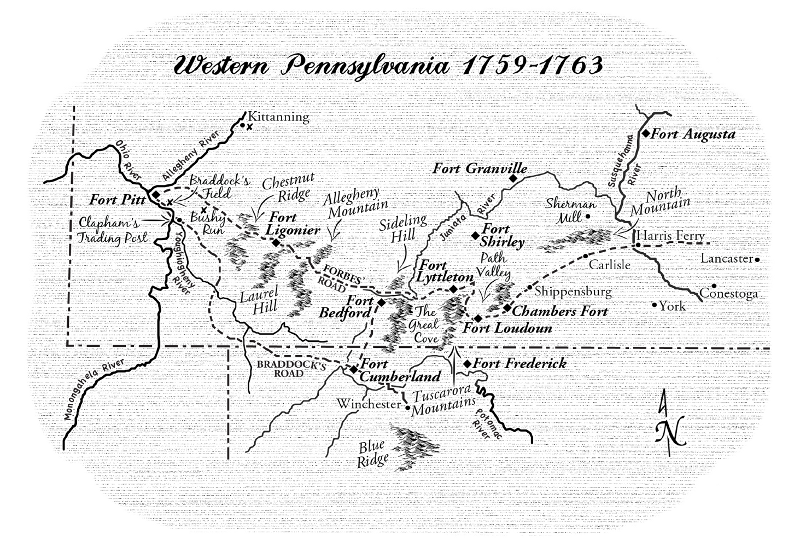

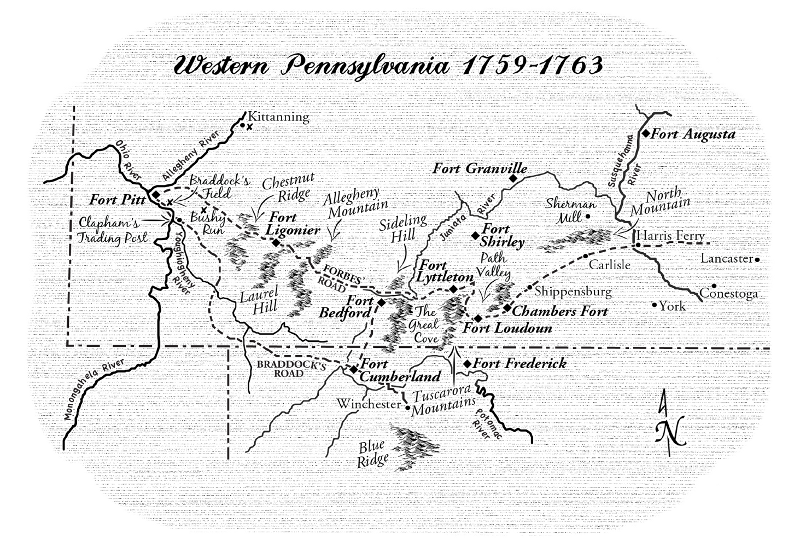

Forbes, unlike Braddock, was a pragmatic and adaptable commander. He studied the lessons of the past and recognized the folly of rushing headlong into the wilderness. Instead, he proposed a radical, painstaking strategy: to build a new road, directly west from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, through the heart of the formidable Allegheny Mountains. This new route would offer a more secure and logistically sound supply line, avoiding the southern detours of Braddock’s ill-fated path.

The undertaking was Herculean. Forbes himself was a man afflicted by a debilitating illness, often confined to a litter, yet his mind remained sharp and his will unyielding. He assembled a force of some 6,000 troops, a mix of British regulars, including the famed Highland Regiments, and provincial soldiers from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. Among them was a young George Washington, still smarting from Braddock’s defeat, who initially advocated for using and improving Braddock’s old road. However, Forbes, with his superior strategic vision, overruled him, explaining that a new road would offer better terrain, more direct access, and crucially, avoid the psychological baggage of the previous disaster.

The construction of Forbes Road commenced in the summer of 1758. It was a brutal, relentless grind. Thousands of men, armed with axes, shovels, and saws, hacked their way through dense forests, over steep ridges, and across treacherous ravines. The pace was agonizingly slow – often no more than a mile or two a day. "We are cutting a road," one soldier wrote, "through a country impassable but for deer and wild beasts." Trees had to be felled, stumps removed, and corduroy roads built across boggy ground. Rivers and streams required bridges, sometimes elaborate structures of logs and stone.

As the road slowly advanced, a chain of fortified outposts was established to protect the supply lines and serve as staging points for the troops. These forts, like Fort Loudoun, Fort Lyttelton, Fort Bedford, and most crucially, Fort Ligonier, were vital for the expedition’s success. Fort Ligonier, built deep in the wilderness and just 50 miles from Fort Duquesne, became the main advanced base, a formidable defensive position that could hold out against French and Native American attacks, allowing Forbes to consolidate his forces and supplies.

The challenges were manifold. Beyond the sheer physical labor, the troops faced the constant threat of ambush from French and Native American scouting parties. Disease, poor sanitation, and meager rations took their toll, leading to desertion and low morale. The dense woods and mountainous terrain were disorienting, and the changing seasons brought heavy rains, turning the nascent road into a muddy quagmire.

Forbes, however, maintained strict discipline and a methodical approach. He understood that speed was less important than security and a reliable supply chain. His strategy was to advance slowly, consolidate, and then move forward again, never overextending his lines of communication. This patient, deliberate approach stood in stark contrast to Braddock’s headlong rush.

Crucially, Forbes understood that military might alone was insufficient. He launched a sophisticated diplomatic offensive, spearheaded by the brave Moravian missionary Christian Frederick Post. Post, with his deep understanding of Indigenous languages and customs, ventured repeatedly into the Ohio Country, engaging with tribal leaders, particularly the Delaware and Shawnee. These efforts culminated in the Treaty of Easton in October 1758, a monumental diplomatic achievement that secured the neutrality, and in some cases, the allegiance, of several key Native American nations who had previously sided with the French. This diplomatic coup critically weakened Fort Duquesne’s defenses, as the French now faced the prospect of fighting without their vital Indigenous allies.

As Forbes’s forces neared Fort Duquesne, a critical setback occurred. Major James Grant, eager for glory, led an unauthorized reconnaissance mission with a large detachment of troops, attempting to surprise the French garrison. Instead, Grant’s forces were discovered, ambushed, and decisively routed on September 14, 1758, suffering over 300 casualties. This costly error underscored Forbes’s wisdom in favoring caution over rash action.

Despite the setback, the advance continued. By mid-November, the main British force, with its heavy artillery and vast supply train, was encamped at Fort Ligonier. The winter was fast approaching, and time was running out. Forbes, despite his worsening health, pushed for a final, decisive push.

On November 24, 1758, the advance guard, including Washington’s Virginians, approached Fort Duquesne. What they found was not a fortified garrison ready for battle, but an eerie silence and the acrid smell of smoke. The French, realizing their Indigenous allies had abandoned them and facing an overwhelming force, had decided to scuttle their strategic fort. They had set it ablaze, destroyed what they could, and retreated down the Ohio River.

On November 25, 1758, the British forces marched into the smoking ruins. The Union Jack was raised, and the site, once a symbol of French power, was renamed Fort Pitt, in honor of William Pitt. The immediate objective was achieved, but the deeper significance was profound. The Forks of the Ohio, the gateway to the West, was now firmly in British hands.

General Forbes, his mission accomplished, would not long enjoy the fruits of his victory. He died in Philadelphia a few months later, in March 1759, his body ravaged by illness but his legacy secured. His road, however, lived on.

Forbes Road immediately became a vital thoroughfare for westward expansion. Settlers, traders, and adventurers followed in the footsteps of the soldiers, pushing the frontier further into the Ohio Country. It facilitated the growth of Pittsburgh from a military outpost into a bustling trading center and, eventually, a major industrial city. The strategic importance of the route continued through subsequent conflicts, including Pontiac’s War and the American Revolution.

Today, much of the original Forbes Road has been subsumed by modern infrastructure. Portions of it align with the historic Lincoln Highway (U.S. Route 30), a testament to its enduring logic as a transportation corridor. Yet, its legacy remains etched into the landscape and the historical memory of Pennsylvania. Historical markers, preserved sections of the road, and reconstructed forts like Fort Ligonier stand as powerful reminders of the epic struggle that unfolded there.

Forbes Road was more than just a military supply line; it was a testament to the power of methodical planning, diplomatic foresight, and sheer human endurance. It was the pathway through which British imperial power asserted itself, laying the groundwork for the future United States. From the ashes of Braddock’s defeat, Forbes carved a new vision, a route that not only conquered a strategic location but also opened a continent, forever changing the destiny of America. Its silent, forested stretches still whisper tales of grit, sacrifice, and the relentless march of empire, reminding us that the foundations of nations are often forged, one arduous mile at a time, through the very wilderness they seek to tame.