The Audacious Dream: Fort Astoria and America’s Pacific Gambit

ASTORIA, OREGON – Perched precariously at the mouth of the mighty Columbia River, where the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean meets the dense green of the Pacific Northwest, lies Astoria, Oregon. Today, it’s a charming, if sometimes misty, coastal town known for its Victorian homes, vibrant arts scene, and a deep-seated maritime heritage. But peel back the layers of its picturesque present, and you’ll discover the gritty, ambitious, and often brutal genesis of what was once America’s audacious gamble on the Pacific: Fort Astoria.

More than just a trading post, Fort Astoria, established in 1811, was a defiant stake in the ground, a declaration of American intent on a continent largely dominated by European powers. It was the brainchild of John Jacob Astor, a German-born fur magnate who, by the early 19th century, was already one of the wealthiest men in the United States. His vision was not merely to trade furs; it was to create a global mercantile empire, stretching from the forests of the American West to the lucrative markets of China. Fort Astoria was to be the linchpin of this grand design.

The Visionary and His Grand Design

John Jacob Astor was a man ahead of his time, possessing a ruthless business acumen matched only by his boundless ambition. He understood that the fur trade, particularly the highly prized sea otter pelts, was a gateway to immense wealth, especially in the Chinese market where they commanded exorbitant prices. But to truly dominate, he needed to control the supply chain from source to sale. This meant establishing a permanent American presence on the Pacific Coast.

In 1810, Astor founded the Pacific Fur Company (PFC), an audacious endeavor designed to challenge the entrenched British dominance of the fur trade, primarily the powerful North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company. His plan was twofold: one expedition by sea, carrying supplies and personnel around Cape Horn, and another overland, blazing a trail through the unexplored wilderness. Both would converge at the mouth of the Columbia River, a location famously scouted by Lewis and Clark a few years prior, recognizing its strategic importance as a natural harbor and gateway to the interior.

As Washington Irving, a contemporary of Astor and author of "Astoria," later wrote, Astor’s plan was "of a magnificent scale, and calculated to elevate the commerce of his country." It was a bold assertion of American economic power and territorial aspiration, long before the phrase "Manifest Destiny" had even been coined.

The Perilous Journeys: Sea and Land

The journey to establish Fort Astoria was fraught with peril, a testament to the unforgiving nature of the early American frontier. The sea expedition, aboard the brig Tonquin, departed New York in September 1810. Under the command of Captain Jonathan Thorn, a former naval officer known for his strict discipline and irascible temper, the voyage was plagued by internal strife and tragic incidents. The Tonquin arrived at the mouth of the Columbia in March 1811, after a harrowing journey that saw crew members desert and relations between Thorn and the Astorians deteriorate rapidly.

The overland expedition, led by Wilson Price Hunt, faced even more grueling challenges. Intending to follow much of the Lewis and Clark trail, Hunt’s party instead became lost in the vastness of the American West, enduring starvation, bitter cold, and hostile encounters with Native American tribes. They were scattered, desperate, and arrived at the fledgling Fort Astoria in piecemeal fashion, many months later than planned, having suffered immense hardship. Their journey, though a commercial failure, provided invaluable geographical knowledge of the American interior.

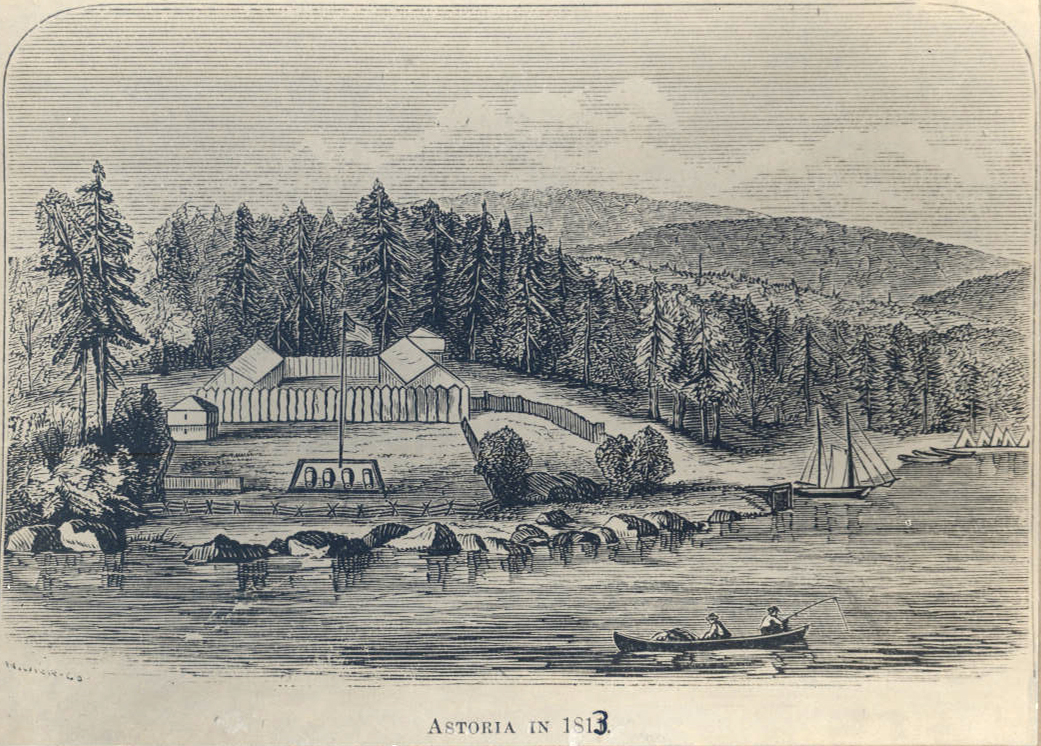

Upon arrival, the Astorians faced the immediate task of constructing their fort. The site, chosen for its defensibility and access to the river, was a dense forest. Men, many of whom were unaccustomed to manual labor, toiled relentlessly to clear land, cut timber, and erect the palisades and buildings that would form the heart of their enterprise. They named their new outpost "Astoria" – a fitting tribute to the visionary who had sent them into the wilderness.

Life at the Edge: Hardship and Ambition

Life at Fort Astoria was a constant struggle against the elements, isolation, and fierce competition. The initial years were marked by relentless toil, disease, and a sense of vulnerability. The fort itself was a rough-hewn affair, a collection of log structures surrounded by a stockade, designed more for function than comfort. Its inhabitants were a motley crew: American clerks, Canadian voyageurs, French-Canadian trappers, and a few Native American interpreters.

Relations with the local Chinook and Clatsop tribes were complex. While the Astorians depended on them for furs, knowledge of the land, and sometimes even food, there was an underlying tension and mistrust. The infamous fate of the Tonquin itself, after it left Astoria to trade further north, serves as a grim reminder of the dangers. Captain Thorn’s arrogance and disrespect towards the Nuu-chah-nulth people on Vancouver Island led to a violent confrontation in which the ship was captured and most of its crew massacred, a stark lesson in the perils of cross-cultural encounters on the frontier.

Adding to the Astorians’ woes was the relentless pressure from their British rivals, particularly the North West Company, who viewed Astor’s incursion into their traditional territory with thinly veiled hostility. Skirmishes over trapping grounds, attempts to sway Native American allegiances, and intense commercial rivalry were constant features of life at the fort. Despite these challenges, the Astorians managed to send furs back to China and establish a rudimentary network of trading posts in the interior.

The Shadow of War: A Dream Undone

Just as Astor’s grand enterprise seemed to be gaining a foothold, external events conspired against it. The War of 1812 erupted between the United States and Great Britain, sending shockwaves across the continent, even to its remote western outpost. News of the war reached Astoria in early 1813, bringing with it the chilling realization of their extreme vulnerability. Isolated and thousands of miles from American reinforcements, Fort Astoria was a tempting prize for the British.

In October 1813, the British warship HMS Raccoon was dispatched to seize Astoria. However, before its arrival, a pragmatic, if humiliating, decision was made by the Astorians on the ground. Fearing capture and the loss of all their assets, and facing a lack of support from the distant United States government, they opted to sell the entire Pacific Fur Company operation, including Fort Astoria, to the North West Company. The transaction, completed on October 23, 1813, effectively surrendered Astor’s dream to his rivals.

When the HMS Raccoon finally arrived in December, its captain, William Black, was reportedly furious to find the fort already under British control, deprived of the glory of capturing it. He nonetheless formally claimed the territory for Britain, renaming the post Fort George, in honor of King George III. Astor’s audacious American gambit on the Pacific had been thwarted, not by direct military conquest, but by the relentless pressure of war and the harsh realities of frontier economics.

Legacy and Rebirth: From Fort George to Astoria

The British occupation of Fort George lasted for several years. Following the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, which ended the War of 1812, all captured territories were to be returned to their pre-war owners. While the physical fort remained under British control (first the North West Company, then the Hudson’s Bay Company), the American flag was symbolically re-hoisted over Fort George in 1818, signaling American sovereignty over the territory. This act, though largely symbolic at the time, was crucial in solidifying the United States’ claim to the Oregon Country, a claim that would be fiercely debated with Britain for decades to come.

Despite Astor’s personal failure to establish a lasting fur empire, Fort Astoria’s legacy is profound. It was, unequivocally, the first permanent American settlement on the Pacific Coast, west of the Rocky Mountains. Its very existence, however brief under American management, was a tangible expression of American expansionist ambitions. It proved that the journey was possible, that a foothold could be established, and it laid the groundwork for future American migration and settlement.

The fort itself eventually faded, its original structures decaying and disappearing. The Hudson’s Bay Company eventually relocated its primary operations further upriver to Fort Vancouver. But the town of Astoria persisted, growing slowly through the 19th century, sustained by its fishing and timber industries, always remembering its unique origin story.

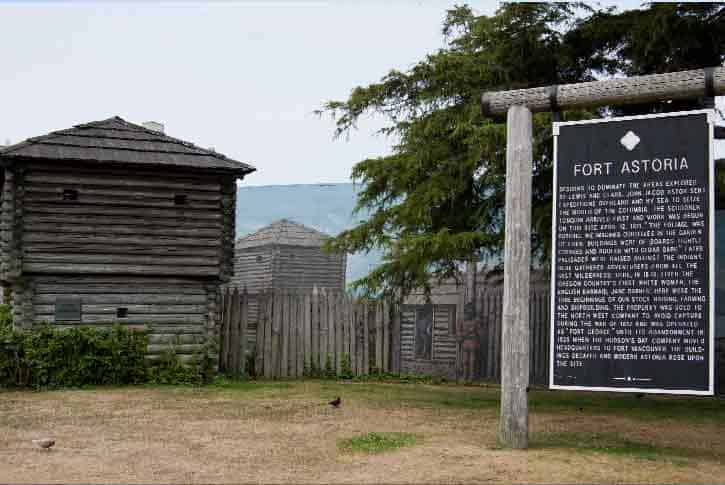

Today, little remains of the original Fort Astoria save for its historical markers and the enduring spirit of its intrepid founders. A reconstructed blockhouse and a small park commemorate the site where American dreams first touched the Pacific. Visitors can stand on the bluff overlooking the Columbia, imagining the arrival of the Tonquin, the arduous construction, and the desperate struggle for survival.

Fort Astoria stands as a powerful reminder that America’s reach to the Pacific was not a foregone conclusion but the result of immense ambition, incredible hardship, and the relentless pursuit of a vision. It was a testament to the pioneering spirit that shaped a nation, an audacious dream that, though temporarily shattered, ultimately paved the way for the United States to become a two-ocean power. Its story is a vital chapter in the larger narrative of American expansion, a tale of enterprise, endurance, and the unyielding allure of the western frontier.