The Autumn of Audacity: Lee’s Last Gambit and the Bristoe Campaign

In the shadow of Gettysburg’s monumental carnage, as the summer of 1863 faded into a crisp autumn, the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War did not fall silent. While the Union celebrated its twin victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, and the Confederacy reeled from the loss of a third of its fighting strength, Robert E. Lee remained a force of audacious will. His Army of Northern Virginia, though battered, was not broken. And for a brief, intense period in October 1863, Lee launched one last, desperate offensive gambit in Virginia, a strategic chess match known as the Bristoe Campaign – a series of maneuvers and sharp, sudden engagements that, while often overshadowed by larger battles, offers a fascinating glimpse into the evolving nature of the war and the enduring genius and flaws of its most prominent generals.

The stage was set by a relative lull. Following their retreat from Pennsylvania, Lee’s Confederates had fallen back to the Rapidan River, while Major General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac occupied the line of the Rappahannock. Both armies licked their wounds, reinforced, and resupplied. Yet, Lee, ever the aggressor, chafed under the strategic initiative held by the Union. With Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s victory at Vicksburg securing the Mississippi River and threatening the Confederacy’s western flank, and Union forces under Major General William S. Rosecrans pushing into Chattanooga, Lee knew that maintaining pressure in Virginia was paramount to drawing Union resources away from other vital fronts. His goal was clear: to turn Meade’s flank, cut his lines of communication and supply with Washington D.C., and force a decisive battle on his own terms.

The Union, too, was undergoing shifts. In September, two corps – XI and XII – had been detached from the Army of the Potomac and sent west to reinforce Rosecrans, significantly reducing Meade’s numerical superiority. This reduction, combined with the strategic imperative to protect the capital, made Meade inherently more cautious, but also acutely aware of the dangers posed by Lee’s renowned flanking maneuvers.

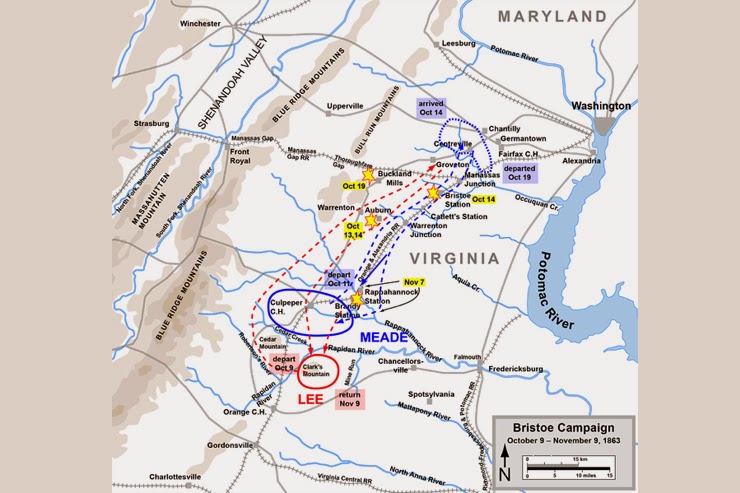

Lee’s plan was audacious, a classic move from his playbook. On October 9, he began his movement, pulling his army out of its positions on the Rapidan and swinging wide around Meade’s right flank, aiming to get between the Army of the Potomac and Washington. His objective was the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, a vital artery for Union supplies. If he could sever that lifeline and position his army across Meade’s line of retreat, he could force Meade to fight at a disadvantage or face starvation and encirclement.

Meade, however, was no longer the somewhat hesitant commander he had been in the immediate aftermath of Chancellorsville. He was growing into his role, learning from his experiences, and, crucially, he had excellent cavalry under Major General Alfred Pleasonton keeping a watchful eye on Confederate movements. When Pleasonton’s scouts reported the scale of Lee’s flanking march, Meade quickly understood the gravity of the situation. He had no intention of being trapped. On October 11, he ordered a rapid, disciplined retreat northward along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, initiating a grueling footrace that would define the campaign.

For the next few days, the armies engaged in a tense game of cat and mouse. Meade’s corps, sometimes marching thirty miles in a single day, raced to stay ahead of Lee’s pursuing columns. The dust raised by thousands of men, horses, and wagons choked the roads, but the Union retreat was orderly, a testament to improved command and control. Lee, pushing his men hard, was determined to catch a portion of Meade’s army isolated.

The first significant clash came on October 13, near the small crossroads of Auburn. Confederate Major General J.E.B. Stuart, leading Lee’s cavalry screen, found himself in a precarious position. While scouting, he stumbled upon elements of Union Major General Gouverneur K. Warren’s II Corps, which had become separated from the main body of Meade’s army. For hours, Stuart’s cavalry was effectively trapped between Warren’s infantry and the approaching Confederate columns of Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell’s corps. It was a near-disaster for Stuart, a "hide-and-seek" game that could have seen his command annihilated. Only by a stroke of luck and skillful maneuvering under the cover of darkness and fog did Stuart manage to extricate his men, slipping through the Union lines undetected. The incident highlighted the fluidity and inherent risks of such rapid movements, a "near-miss" that could have significantly altered the course of the campaign.

The very next day, October 14, the campaign reached its bloody zenith at Bristoe Station. Meade’s retreating columns were nearing the vital railroad junction, with Warren’s II Corps acting as the rearguard. Lee, believing he had caught the Union army in a vulnerable position, pressed his advantage. Lieutenant General A.P. Hill, leading the Confederate Third Corps, saw what he perceived as a straggling Union force and, with his characteristic impetuosity, ordered an immediate attack.

Hill’s target was the Union II Corps, veterans of countless battles, including Gettysburg, and now led by the tenacious Warren. Critically, Warren had deployed his men in a strong defensive position, utilizing the embankment of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad as a natural breastwork. As Hill’s brigades, primarily those of Major General Henry Heth and Brigadier General R. Lindsay Walker, surged forward, they were met by a devastating hail of fire from the concealed Federals. The Union soldiers, well-positioned and disciplined, delivered a shattering repulse.

The fighting was fierce but relatively short. The Confederates, advancing across open ground, were mowed down. Brigadier General John R. Cooke’s brigade suffered particularly heavy casualties, losing over a third of its men in a matter of minutes. The attack was poorly coordinated, and Hill’s eagerness to engage without proper reconnaissance proved costly. Two Confederate artillery batteries, unwisely advanced to support the infantry, were quickly overrun and captured by Union counterattacks.

As the smoke cleared, the Confederates had suffered over 1,300 casualties, including several brigadier generals killed or wounded, while the Union lost around 540 men. It was a sharp, stinging rebuke to Lee’s offensive. Lee himself rode up to Hill after the battle, visibly displeased. His famous, pointed question to Hill echoed the sentiment of many: "General Hill, why did you bring on this fight?" The engagement at Bristoe Station was a tactical Union victory, a clear demonstration of the resilience and fighting prowess of the Army of the Potomac, even when on the defensive. It also underscored the growing difficulty for the Confederacy to achieve decisive tactical victories against well-positioned Union forces.

After Bristoe Station, Lee realized his flanking maneuver had failed. Meade had successfully avoided being trapped and had inflicted a painful blow. Lee then destroyed sections of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, hoping to disrupt Union supply lines and force Meade to react. This act of "railroad wrecking," though destructive, was a tacit admission that his primary objective had eluded him. He then withdrew his army behind the Rappahannock River, settling into a strong defensive position along Mine Run.

Meade, now back on the offensive, decided to pursue Lee. He saw an opportunity to finally bring Lee to battle on ground of his own choosing. In late November, he advanced his army, attempting another flanking maneuver around Lee’s right, hoping to surprise the Confederates. However, Lee anticipated Meade’s move and quickly entrenched his men in formidable earthworks along the western bank of Mine Run.

When Meade’s engineers and reconnaissance parties surveyed the Confederate positions on November 29, they were met with a sobering sight. Lee’s defenses were incredibly strong, a maze of earthworks, abatis (felled trees with sharpened branches), and artillery positions. Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, who had played a crucial role at Bristoe, was tasked with leading a potential assault. After personally reconnoitering the enemy lines, Warren delivered a grim assessment: a frontal assault would be a bloodbath, akin to the disastrous Union charges at Fredericksburg. Faced with the prospect of another senseless slaughter, Meade, with characteristic caution and humanity, made the difficult decision to call off the attack. He famously stated, "I could not ask my men to go through what would be almost certain destruction."

With the onset of winter and the futility of breaking Lee’s fortified lines, the Mine Run Campaign, and thus the larger Bristoe Campaign, effectively ended. Both armies went into winter quarters, exhausted but largely intact.

The Bristoe Campaign, while not featuring the monumental scale of Gettysburg or the prolonged sieges of Vicksburg, holds significant lessons. For Lee, it marked the end of his capacity to launch grand, sweeping offensives in Virginia with the aim of destroying the Army of the Potomac. His army, though still capable of fierce defense, was steadily losing its offensive punch. The numerical disparity was growing, and the strategic landscape was shifting irrevocably against the Confederacy. Lee’s audacious gamble failed not due to a lack of tactical skill on his part, but due to Meade’s improved generalship, the resilience of the Union army, and the inherent difficulties of coordinating complex maneuvers against a wary and well-led opponent.

For Meade, the campaign was a quiet triumph. He had successfully defended Washington, avoided Lee’s traps, and inflicted a tactical defeat at Bristoe Station. His cautious, methodical approach, often criticized as lacking aggressiveness, proved strategically sound. He demonstrated a clear understanding of the need to preserve his army and choose his battles wisely, foreshadowing the attrition warfare that would come to define the final year of the conflict. The Army of the Potomac emerged from the campaign with increased confidence, having shown its ability to both retreat effectively and fight tenaciously.

In the grand narrative of the Civil War, the Bristoe Campaign often fades into the background, overshadowed by the titanic struggles that preceded and followed it. Yet, it was a pivotal moment – Lee’s last major offensive effort in Virginia for 1863, a testament to his enduring will to fight, and a quiet validation of Meade’s growing competence. It demonstrated that even in autumn, when the leaves fell, the fight for the Union was as intense and as strategically complex as ever, a campaign of movement and skirmish that spoke volumes about the shifting tides of the conflict.