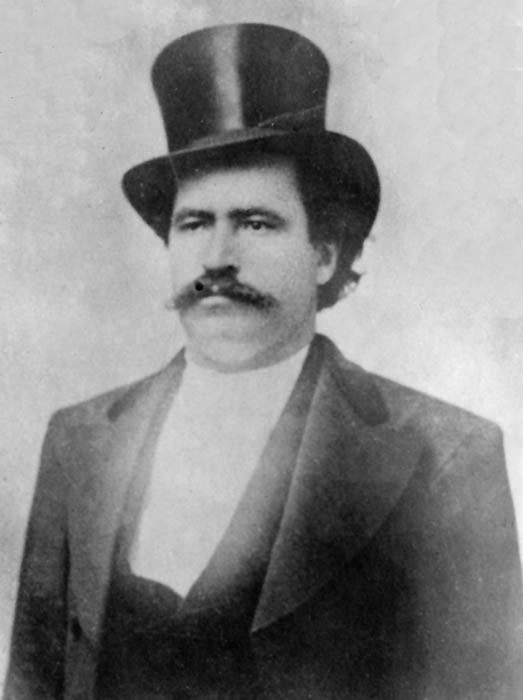

The Ballad of "Rowdy" Joe Lowe: A Gunfighter’s Reckoning in the Untamed West

In the annals of the American Old West, where legends were forged in the crucible of dust, desperation, and gunpowder, few figures embodied the raw, untamed spirit of the frontier quite like Joseph "Rowdy" Joe Lowe. Not a lawman, nor a celebrated outlaw in the vein of Jesse James or Billy the Kid, Lowe was a more complex, volatile character: a gambler, a saloon keeper, a ruthless gunfighter, and a man whose very presence seemed to ignite chaos. His life, a turbulent odyssey across the nascent cattle towns and mining camps, serves as a stark, unromanticized testament to the brutal realities and fleeting justice of a nation still finding its footing.

Born Joseph Lowe around 1845 in Ohio, his early life remains largely obscure, a common trait among those who would later carve out notorious reputations on the fringes of civilization. What is known is that he eventually drifted west, drawn by the siren call of opportunity and the promise of a life unburdened by the conventions of established society. He first surfaced prominently in Kansas, a territory rapidly transforming into the epicentre of the cattle trade. Here, in towns like Newton and Wichita, Lowe would begin to etch his name into the rough-hewn ledger of frontier history, not with deeds of heroism, but with a trail of violence and infamy.

Newton, Kansas, in the early 1870s, was a microcosm of the Old West’s explosive growth and inherent dangers. As the railhead for the Chisholm Trail, it swelled with cowboys fresh off long drives, flush with cash, and eager for the saloons, gambling dens, and dance halls that proliferated along its dusty main street. It was here, in August 1871, that "Rowdy" Joe Lowe played a central role in what historians would dub the "Newton General Massacre," one of the most chaotic and deadly shootouts in cattle town history.

The catalyst for the massacre was not Lowe himself, but a complex web of rivalries, alcohol, and the casual brutality of the era. The night of August 19th saw a dispute between two men, Mike McCluskie and Arthur Pryce, escalate into a fatal shooting. McCluskie, a local gambler and general troublemaker, shot and killed Pryce, a friend of Lowe’s. Pryce had been trying to disarm McCluskie, who was already in a drunken rage. The immediate aftermath was tense, but the full explosion was yet to come.

Hours later, in the early morning of August 20th, a revenge plot unfolded at the back of the Red Front Saloon. Lowe, seeking retribution for his friend’s death, along with several confederates, confronted McCluskie. What followed was an absolute melee. A young, unknown gunman named Billy Bailey, who was allied with Lowe, burst into the saloon and fired a shot at McCluskie. McCluskie returned fire, hitting Bailey. In the ensuing pandemonium, Lowe drew his own weapon, a Colt revolver, and emptied it into McCluskie, reportedly firing five shots.

But the violence didn’t stop there. As McCluskie lay dying, the saloon erupted into a free-for-all. Historians like Robert M. Wright, in his book "Dodge City, The Cowboy Capital," described the scene as utterly anarchic, with men firing indiscriminately in the smoky, crowded room. When the dust settled, five men were dead or mortally wounded, and several others injured. McCluskie was gone, as was Billy Bailey, who succumbed to his wounds. Two innocent bystanders, one a local farmer and another a cowboy, also lay dead, caught in the crossfire of someone else’s vendetta. The Newton General Massacre sent shockwaves through the frontier, a stark reminder of how quickly life could be extinguished in the lawless West. Lowe, despite his central role, managed to avoid immediate arrest, disappearing into the vastness of the plains, his reputation as a man not to be trifled with firmly cemented.

His flight from Newton led him to Wichita, another burgeoning cattle town where his name already carried weight. Wichita, much like Newton, struggled to balance its wild, cowboy-driven economy with aspirations of becoming a respectable city. Lowe, with his saloon-keeping and gambling interests, often found himself at odds with the emerging forces of law and order. He continued his pattern of confrontation, his quick temper and even quicker draw making him a feared figure.

"Rowdy" Joe’s movements were dictated by the flow of the cattle trade and the availability of opportunities for gambling and illicit enterprise. From Kansas, he drifted south to Texas, a state even more synonymous with the untamed frontier. In towns like Denison and Fort Worth, Lowe continued to ply his trade, running saloons that often doubled as gambling halls and fronts for various unsavory activities. It was in Denison, in 1873, that he became embroiled in another notorious gunfight, this time with a different, equally volatile figure: Billy Thompson.

Thompson, a cousin of the famous Ben Thompson, was himself a notorious gunfighter and gambler. The conflict between Lowe and Thompson reportedly stemmed from a gambling dispute, a common flashpoint for violence in the era. The details are somewhat murky, but accounts suggest a shootout on the streets of Denison, a chaotic exchange of gunfire that left Thompson wounded and Lowe once again escaping relatively unscathed, his legend growing with each confrontation. "He was a man who seemed to thrive on conflict," noted one contemporary account, "always ready with a gun or a sharp word, never backing down from a challenge."

Lowe’s itinerant life continued, taking him further west as the frontier expanded. He spent time in Colorado, particularly Denver, a booming mining town that attracted its own share of desperate characters, fortune seekers, and professional gamblers. Here, he continued his saloon ventures, often operating on the fringes of legality, always with one eye on his competitors and the other on the local law enforcement, who, like in many frontier towns, often had a strained relationship with the powerful saloon owners.

By the late 1870s and early 1880s, Lowe’s path eventually led him to Arizona Territory, a land even more rugged and less settled than Kansas or Texas. Here, in the raw, untamed landscape of the American Southwest, "Rowdy" Joe Lowe would finally meet his end. The circumstances of his death, like much of his life, were steeped in the casual brutality of the frontier, a stark reminder that even the most feared gunfighter could fall to an unexpected bullet.

In 1880, Lowe was in the remote town of Trinidad, Arizona, engaged in a land dispute, a common source of conflict in a territory where property lines were often vague and claims fiercely contested. His adversaries were a group of squatters, who, unlike the professional gunmen he had faced in the past, likely saw Lowe not as a legendary figure but as a threat to their livelihood. On a fateful day in June 1880, Lowe was ambushed. Accounts vary, but it is generally believed that he was shot from behind, struck by multiple bullets fired by the squatters he had been feuding with. He died instantly, a sudden, inglorious end for a man who had survived countless face-to-face confrontations. There was no grand shootout, no heroic last stand, just a brutal, premeditated act of violence that brought a tumultuous life to an abrupt close.

"Rowdy" Joe Lowe’s legacy is not one of admiration, but rather a chilling testament to the darker side of the Old West. He was not a romanticized outlaw fighting for a cause, nor a valiant lawman upholding justice. Instead, he was a product of his environment, a man whose quick temper and proficiency with a gun made him a force to be reckoned with, but also a figure who contributed to the very lawlessness he exploited. His life highlights the precariousness of existence on the frontier, where personal honor could be a matter of life and death, and where disputes were often settled not in courtrooms, but with lead.

His story is intertwined with that of many other figures of the era – Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, and Doc Holliday, all of whom operated in some of the same towns and circles. Unlike these more famous individuals, who often had a dual nature as lawmen or figures of complex moral ambiguity, Lowe remained largely a force of destruction. He embodied the quintessential "bad man" of the frontier, a man driven by self-interest, prone to violence, and ultimately, a victim of the very system he helped to perpetuate.

The Newton General Massacre remains his most infamous chapter, a stark illustration of how quickly order could disintegrate on the frontier. It was an event that forced communities to confront the cost of their unchecked growth and the need for stronger law enforcement. Lowe’s role in it, as well as his subsequent shootouts and turbulent life, underscore the brutal reality that for every noble cowboy or principled lawman, there were dozens of figures like "Rowdy" Joe, whose lives were a constant dance with death, their stories serving as a somber counterpoint to the more celebrated narratives of the American West.

In the end, Joseph "Rowdy" Joe Lowe faded from memory, his name less celebrated than many of his contemporaries, yet his life story remains a vital, if grim, piece of the Old West mosaic. It’s a story not of heroism, but of survival, violence, and the ultimate reckoning that awaited many who dared to live by the gun in an era where the law was often a distant whisper, and personal power was measured in the cold steel of a revolver. He was a force of nature, untamed and unpredictable, a true reflection of the wild, unforgiving land he roamed until his final, abrupt moment.