The Bay Under Siege: How the War of 1812 Ravaged the Chesapeake

The placid, shimmering waters of the Chesapeake Bay, a vital artery of commerce and a picturesque natural wonder, belie a tumultuous past. For nearly two years during the War of 1812, this vast estuary, stretching across Maryland and Virginia, transformed into a brutal theatre of conflict, a battleground where the might of the British Royal Navy met the resilience of American defenders and the desperation of civilians caught in the crossfire. The Chesapeake Bay Blockade was not merely a military strategy; it was a campaign of psychological warfare, economic strangulation, and targeted destruction that left an indelible mark on the American psyche and landscape.

When the United States declared war on Great Britain in June 1812, the conflict initially focused on the Canadian frontier and the high seas. However, by early 1813, the British, seeking to exert pressure on the young American republic and disrupt its economy, shifted their gaze to its vulnerable coastline. The Chesapeake Bay, with its deep channels leading directly to the capital city of Washington D.C., and its numerous rivers providing access to bustling port towns and fertile farmlands, presented an irresistible target. It was, in essence, the soft underbelly of the nation.

The Scourge of the Chesapeake Arrives

The arrival of the British fleet in February 1813 marked the beginning of what many Americans would come to call "the Scourge of the Chesapeake." Under the command of Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, a man known for his aggressive tactics and a particular disdain for American defiance, the British adopted a strategy of relentless raids and economic paralysis. Their objectives were clear: destroy American shipping, disrupt trade, confiscate supplies, and instill a pervasive sense of fear and insecurity among the populace.

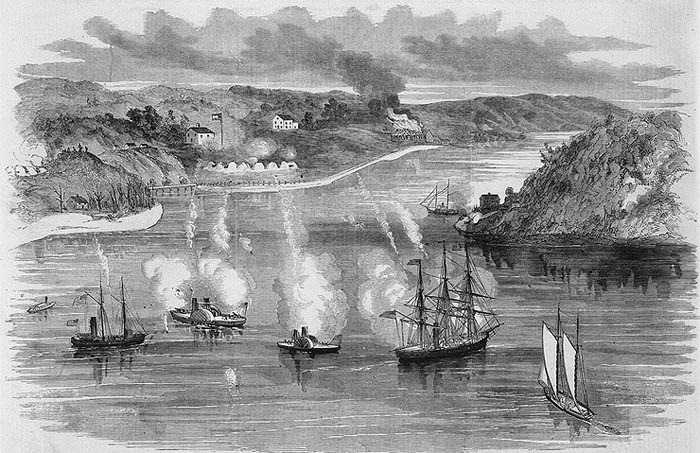

Cockburn’s flotilla, consisting of frigates, sloops, and smaller gunboats, quickly established dominance. They set up a formidable blockade at the mouth of the Bay, effectively choking off maritime trade to vital ports like Baltimore, Annapolis, and Alexandria. American merchant vessels found themselves trapped or risked capture, leading to a precipitous decline in economic activity. The region, heavily reliant on waterborne commerce for its agricultural products and manufactured goods, began to suffocate.

The raids soon followed. Cockburn’s men, often landing under cover of darkness, would sweep through waterfront towns and plantations. Havre de Grace, a small but strategically located town at the head of the Bay, was among the first to suffer. In May 1813, Cockburn personally led a landing party that burned most of the town, destroying homes, warehouses, and the cannon battery that had attempted to resist them. Accounts from the time describe scenes of utter devastation, with residents fleeing in terror as their livelihoods went up in smoke. "The wanton destruction of property, the barbarous treatment of the inhabitants, and the indiscriminate plunder," reported one American newspaper, "excited a universal indignation."

Similar assaults followed in quick succession. Fredericktown and Georgetown on the Sassafras River, Frenchtown on the Elk River – town after town fell victim to the British torch and plunder. Farms were stripped of livestock and crops, and enslaved people were often encouraged to defect, promising them freedom and a chance to join the British forces.

Barney’s Mosquito Fleet: A Glimmer of Resistance

Facing an overwhelming naval power, the American response was initially piecemeal and largely ineffective. State militias were poorly trained and equipped, and the nascent U.S. Navy was stretched thin. However, a remarkable figure emerged to offer a glimmer of resistance: Commodore Joshua Barney. A privateer hero of the Revolutionary War, Barney was granted command of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, an audacious project comprising a fleet of shallow-draft gunboats, barges, and small schooners.

Barney’s "mosquito fleet," as it was affectionately known, was designed not to challenge the British in pitched naval battles, but to harass, impede, and frustrate them. His strategy was one of guerrilla warfare on the water. With their light draft, Barney’s vessels could navigate the Bay’s shallow creeks and rivers where the larger British ships dared not venture, launching surprise attacks and then retreating to safety. "These boats," Barney wrote, "will be enabled to give them a great deal of trouble."

Throughout 1813 and into 1814, Barney’s Flotilla engaged the British in a series of skirmishes. While never achieving a decisive victory, they proved to be a constant thorn in Cockburn’s side. At the Battle of St. Jerome Creek in June 1814, Barney’s gunboats bravely faced a superior British force, inflicting damage and delaying their movements. His presence alone offered a much-needed morale boost to the beleaguered American population and forced the British to expend considerable resources simply to track and contain his nimble fleet.

The Desperate Choice: Enslaved People and the British Promise

One of the most complex and poignant aspects of the Chesapeake Bay Blockade was the role of enslaved people. For those held in bondage on the plantations lining the Bay, the arrival of the British offered a desperate, if uncertain, path to freedom. The British, keen to disrupt the American economy and manpower, actively encouraged enslaved people to defect.

Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation during the Revolutionary War had set a precedent, and now, British officers reiterated the promise of freedom to any enslaved person who reached their lines and offered their services. Thousands made the perilous journey, risking recapture, brutal punishment, and the dangers of the open water to reach the British ships. They served as guides, laborers, and even soldiers, forming the "Corps of Colonial Marines," a unit that would later fight alongside the British against their former masters.

This exodus had a profound impact on the region. Plantation owners faced economic ruin as their labor force dwindled, and the social fabric of the slaveholding South was further strained. For the enslaved, it was a moment of agonizing choice, a gamble for liberty in the midst of war, often exchanging one form of servitude for another under the British flag, but with the hope of a better future.

The War’s Climax: Washington in Ashes, Baltimore Holds

By the summer of 1814, the British, having defeated Napoleon in Europe, were able to commit more resources to the American front. The Chesapeake Bay Blockade entered its most destructive phase. Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, commanding a larger fleet, joined Cockburn, and their combined forces aimed for a decisive strike. The target: Washington D.C., the young nation’s capital.

On August 19, 1814, a British force of some 4,500 troops landed at Benedict, Maryland, on the Patuxent River. Commodore Barney, realizing his small flotilla could not possibly stop such an invasion, made the agonizing decision to scuttle his ships in the Patuxent to prevent their capture, then joined the land defense with his sailors.

The ensuing Battle of Bladensburg on August 24 was a humiliating defeat for the Americans, often derided as the "Bladensburg Races" due to the chaotic retreat of the militia. The road to Washington was open. President James Madison and his wife Dolley fled the city, with Dolley famously saving the portrait of George Washington from the Executive Mansion.

That evening, the British marched into Washington D.C. and, under Cockburn’s direct supervision, systematically burned the White House, the Capitol Building, the Treasury, and other public structures. It was an act of retribution for American destruction in Canada, and a profound psychological blow. The capital of the United States lay in ashes, a stark testament to the vulnerability of the nation.

Flushed with their success, the British next turned their attention to Baltimore, a bustling port city known for its privateers and strong anti-British sentiment. However, Baltimore was better prepared. Its defenses included Fort McHenry, strategically positioned to guard the harbor entrance. On September 13, 1814, the British launched a massive bombardment of the fort. For 25 hours, rockets and cannonballs rained down, but the fort’s defenders, under Major George Armistead, held firm.

Simultaneously, a British land force attempted to advance on the city but was repulsed by entrenched American militia and regular troops. The death of Major General Robert Ross, the commander of the land forces, dealt a significant blow to British morale. By the morning of September 14, seeing that Fort McHenry had withstood the onslaught, the British withdrew. It was during this bombardment that Francis Scott Key, observing from a truce ship, penned the verses that would become "The Star-Spangled Banner," a powerful symbol of American resilience.

Legacy and Lessons Learned

The Chesapeake Bay Blockade officially ended with the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814, though its effects lingered for months as British ships slowly departed. The blockade was a brutal and costly episode in American history. Economically, the region was devastated, its trade crippled, and its agricultural output disrupted. The human cost was immense, not only in lives lost but in the widespread fear, displacement, and destruction of property.

However, the blockade also forged a stronger sense of national identity. The burning of Washington, while humiliating, galvanized American resolve. The successful defense of Baltimore, particularly the stand at Fort McHenry, became a powerful symbol of American tenacity and patriotism. The war on the Chesapeake underscored the critical need for a robust naval defense and improved coastal fortifications.

Today, as one cruises the tranquil waters of the Chesapeake Bay, the scars of the War of 1812 are largely hidden. Yet, the history remains etched in the stories of the towns that burned, the resilience of communities that rebuilt, and the desperate choices made by those seeking freedom. The Chesapeake Bay Blockade stands as a vivid reminder of a time when the heart of the young American republic was under direct siege, and its very survival hung in the balance on the shores of its most vital waterway.