The Bitter Dawn on Powder River: A Faltering First Blow in the Great Sioux War

Montana Territory, March 17, 1876. The biting wind of the northern plains, a relentless sculptor of snow and ice, howled its ancient song across a land poised on the brink of cataclysm. In the pre-dawn darkness, a column of U.S. cavalrymen, their breath pluming like smoke signals in the frigid air, prepared to strike. Their target: a sleeping village of Northern Cheyenne and Oglala Lakota Sioux, nestled along the banks of the Powder River. This was to be the opening salvo of the Great Sioux War, a conflict born of broken treaties, manifest destiny, and the insatiable American hunger for gold and land. Yet, what unfolded that bitter dawn was not the decisive victory the U.S. command craved, but a complex, controversial, and ultimately disheartening episode that foreshadowed the brutal campaign to come.

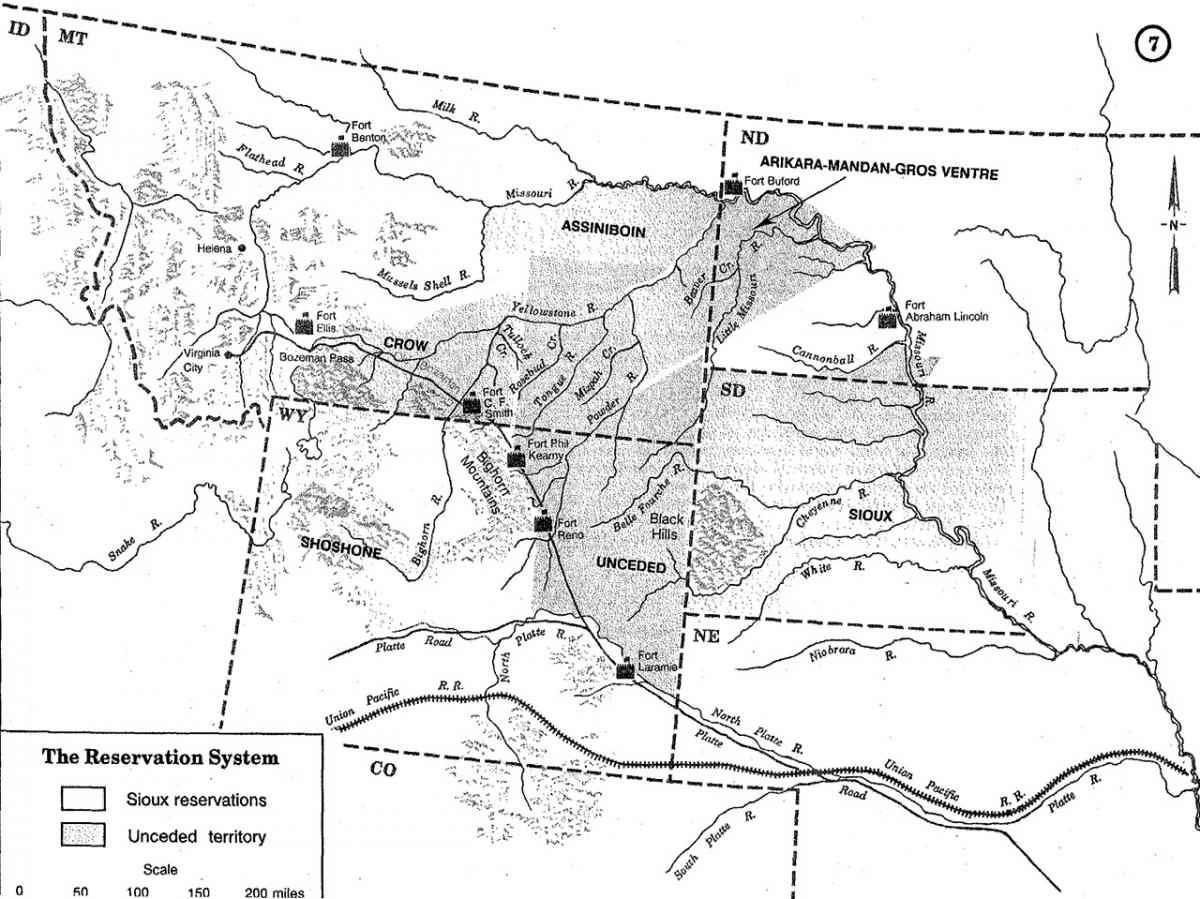

The seeds of the Great Sioux War were sown long before the first shot was fired at Powder River. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie had ostensibly guaranteed the Lakota and their allies a vast reservation, including the sacred Black Hills, "for as long as the grass shall grow." But the discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, confirmed by George A. Custer’s expedition, shattered this fragile peace. The U.S. government, under immense public pressure, quickly moved to acquire the Black Hills, ignoring the treaty’s stipulations. When the Lakota, led by spiritual leaders like Sitting Bull and war chiefs like Crazy Horse, refused to sell, the government issued an ultimatum in December 1875: return to their designated agencies by January 31, 1876, or be deemed "hostile." It was an impossible demand in the dead of winter, effectively a declaration of war.

General George Crook’s Winter Offensive

Among the military leaders tasked with enforcing this decree was Brigadier General George Crook, a seasoned veteran of the Civil War and the Indian Wars. Crook, known for his pragmatic approach and often for his respect for his Native American adversaries, believed that a winter campaign offered the best chance for success. He reasoned that the deep snows and extreme cold would immobilize the nomadic tribes, making them vulnerable to attack. Supplies would be scarce, horses weak, and the element of surprise easier to achieve. His plan was ambitious: three converging columns – one from Fort Abraham Lincoln under General Alfred Terry, one from Fort Fetterman under Colonel John Gibbon, and his own from Fort Fetterman, heading north.

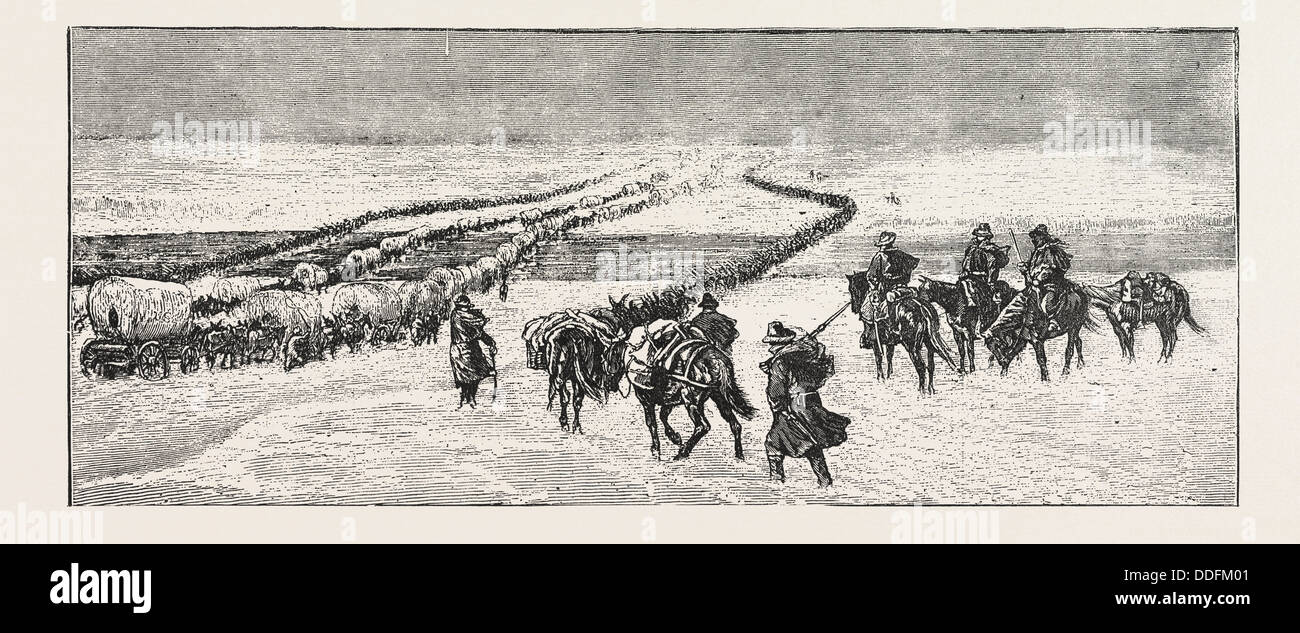

Crook’s column, designated the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, departed Fort Fetterman, Wyoming Territory, on March 1, 1876. It comprised ten companies of the 2nd and 3rd U.S. Cavalry, two companies of the 4th U.S. Infantry, and a detachment of civilian packers and guides, numbering over 1,000 men. Among them was Colonel Joseph J. Reynolds, a veteran officer who would play a pivotal and controversial role in the coming battle.

The march was grueling. Deep snowdrifts, temperatures plummeting to -20°F, and relentless winds tested the limits of men and beasts. Frostbite was common, and the horses suffered terribly. On March 16, a detachment of Crow and Shoshone scouts, led by the experienced Frank Grouard, reported a large Indian village on the Powder River. It was the encampment of Northern Cheyenne under Chief Old Bear, along with some Oglala Lakota. They were precisely the "hostiles" Crook sought, but not the immense combined force of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse that would later gather.

The Attack: Chaos in the Cold

Crook, keen to maintain the element of surprise, ordered Colonel Reynolds to take six companies of cavalry – approximately 370 men – and launch a dawn attack. Crook himself, along with the infantry and supply train, would follow at a slower pace. Reynolds’s orders were clear: capture the village, secure the pony herd, and destroy any supplies or lodges that could not be carried away. The goal was not necessarily to kill as many warriors as possible, but to cripple the tribe’s ability to resist by taking their horses and destroying their winter provisions, forcing them to surrender.

At first light on March 17, Reynolds’s command swept down upon the unsuspecting village. The sudden crack of rifle fire shattered the dawn’s fragile peace. Women, children, and elders, jolted from their sleep, scrambled from their tipis into the biting cold. Warriors, caught off guard, grabbed their weapons and made a desperate stand, providing cover for their families to flee into the surrounding bluffs and ravines.

The initial charge was successful in overrunning the village. The cavalrymen poured in, encountering stiff but disorganized resistance. The true prize, as Reynolds understood, lay in the herd of ponies, numbering some 700 animals, which represented the lifeblood of the village. Captain Henry E. Noyes, with a detachment, managed to cut off and capture the majority of the herd, driving them into a ravine.

However, the battle quickly devolved into chaos. Instead of systematically securing the village and its contents, Reynolds’s command became fragmented. Some soldiers engaged in skirmishes with the retreating warriors, while others began looting the tipis. Critically, no organized effort was made to pursue the fleeing villagers or to fully secure the captured pony herd. As the Cheyenne and Lakota warriors, many now dismounted but driven by fierce determination, regrouped in the surrounding terrain, they began to return fire, harassing the soldiers.

A Pyrrhic Victory and a Disastrous Retreat

Under pressure from the returning warriors, Reynolds made a series of critical errors. He ordered the lodges to be burned, destroying invaluable winter provisions, robes, and personal belongings. This act, while fulfilling part of his orders, also fueled the tribes’ desperate resistance. The burning of homes and the loss of food in such harsh conditions meant certain death for many if they could not find refuge.

But perhaps Reynolds’s most significant blunder was his decision to retreat prematurely. Despite having captured the village and its pony herd, and with his men still holding the ground, he ordered a withdrawal, leaving behind a mortally wounded soldier and the bodies of several others. His justification was the increasing pressure from the rallied warriors and the need to consolidate his position.

The retreat was a disaster. The captured ponies, many still wild and unaccustomed to being driven by soldiers, proved difficult to manage. As the cavalry struggled to herd them through the snow, the pursuing warriors, now led by figures like Two Moons and Little Wolf, launched a counterattack, cutting off many of the horses. In the confusion and the worsening weather, the soldiers were forced to abandon hundreds of the captured animals. "The Indians got back about half of the ponies we had taken from them," recalled Captain James F. Wade, a troop commander, encapsulating the frustration.

When Reynolds finally reunited with Crook’s main column the next day, the general was incandescent with rage and disappointment. The "victory" had been hollow. While the village was destroyed, the enemy had not been decisively defeated, nor had their ability to wage war been significantly crippled. They had suffered a terrible loss of homes and supplies, but their fighting spirit remained unbroken, and much of their horse herd was recovered. The U.S. forces had lost four killed and six wounded, and critically, had failed to hold onto their primary objective: the enemy’s logistical base.

The Fallout and Lasting Legacy

General Crook’s assessment of the Powder River engagement was damning. He saw it as a "fiasco" and a testament to poor leadership and discipline. Colonel Reynolds, along with several other officers, faced a court-martial. Reynolds was found guilty of dereliction of duty and other charges, though the verdict was later overturned on a technicality, he was forced to resign. The other officers were acquitted.

The Battle of Powder River, though often overshadowed by the later, more famous engagements of the Great Sioux War, holds significant historical weight. For the U.S. Army, it was a harsh lesson in the realities of winter campaigning and the formidable resilience of their Native American adversaries. It exposed tactical and leadership deficiencies that would plague the army throughout the early stages of the war.

For the Northern Cheyenne and Lakota, the battle was a profound trauma. They lost their homes, their winter stores, and many of their horses, forcing them to endure unimaginable hardship in the brutal cold. Yet, it also served as a powerful rallying cry. The unprovoked attack on a non-hostile village, coupled with the wanton destruction, solidified their resolve to resist. "They drove us out of our homes in the winter," recounted Chief Two Moons, "and now we had nothing but the clothes on our backs. We had to fight."

The survivors of Powder River, angered and dispossessed, sought refuge with the larger encampments of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Their stories of hardship and injustice fueled the growing confederation of tribes, swelling the ranks of warriors who would, just a few months later, inflict crushing defeats on General Crook at the Battle of the Rosebud and, most famously, on General George A. Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The bitter dawn on Powder River was not the decisive blow Crook had envisioned. Instead, it was a tactical misstep, a logistical nightmare, and a moral outrage that inadvertently strengthened the resolve of the very people the U.S. Army sought to subjugate. It stands as a stark reminder of the complexities and tragedies of the American frontier wars, a testament to both military blunders and the enduring spirit of resistance in the face of overwhelming odds. The wind still howls across the Powder River, carrying echoes of that frigid morning, a forgotten prelude to the epic struggles that would define the summer of 1876.