The Brief Candle of Tippecanoe: The Enduring Saga of William Henry Harrison

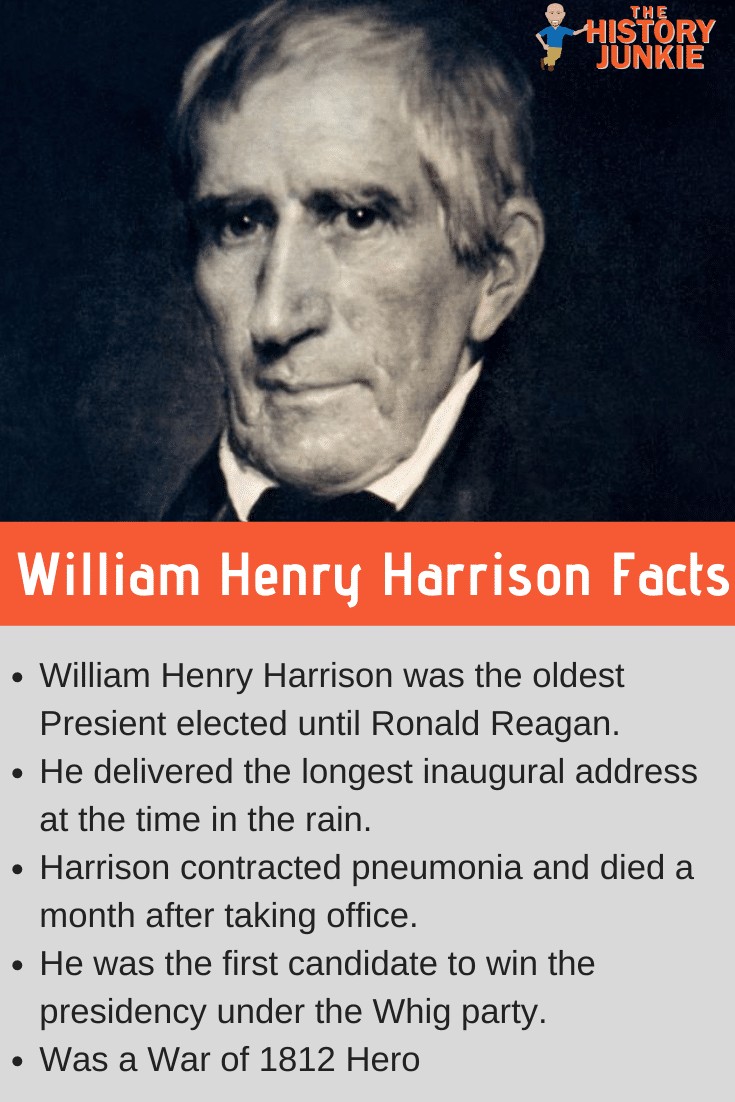

Thirty-one days. That’s all William Henry Harrison got. A presidency briefer than a spring shower, yet one that carved an indelible mark on American history, not for what he achieved in office, but for the dramatic circumstances of his swift departure. He was a war hero, a seasoned politician, and a man who, at 68, became the oldest president elected at the time. His life was a sprawling tapestry of frontier battles and political maneuvering, culminating in a triumph that was tragically short-lived, setting a constitutional precedent that echoed for generations.

Born into the Virginia aristocracy in 1773, the youngest of Benjamin Harrison V’s seven children, young William Henry was destined for a life far grander than his early ambitions suggested. His father was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a governor of Virginia, placing the family firmly within the nation’s founding elite. Initially, William Henry pursued a medical career, studying under the renowned Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia. However, the lure of the military, perhaps ignited by the nascent nation’s expansionist spirit, proved stronger. After his father’s death, facing financial strain, he dropped out of medical school and, in 1791, accepted a commission as an ensign in the U.S. Army.

His military career swiftly took him to the rugged frontier of the Northwest Territory, a land teeming with both opportunity and conflict. He served under the legendary "Mad Anthony" Wayne, learning the harsh realities of frontier warfare and the delicate dance of diplomacy with Native American tribes. Harrison rose through the ranks, proving himself a capable and courageous officer. In 1798, he resigned his commission to embark on a political path, quickly being appointed Secretary of the Northwest Territory and then, in 1799, its first delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives.

His true ascendancy began in 1800 when President John Adams appointed him governor of the newly formed Indiana Territory. For the next twelve years, Harrison presided over a vast domain, navigating complex land treaties and increasingly tense relations with Native American confederacies. His aggressive pursuit of land cessions for white settlement often put him at odds with indigenous leaders, particularly the Shawnee brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, known as The Prophet. They sought to unite tribes to resist American encroachment, advocating for a pan-Indian identity and a return to traditional ways.

The simmering conflict boiled over in November 1811 at the Battle of Tippecanoe. While Tecumseh was away seeking allies, Harrison led a force of approximately 1,000 men against The Prophet’s village of Prophetstown on the Tippecanoe River. In a pre-dawn surprise attack, Native American warriors struck Harrison’s encampment. The ensuing battle was fierce and indecisive in the moment, but Harrison’s forces ultimately repelled the attack and burned Prophetstown. Though casualties were heavy on both sides, the battle was hailed as a decisive victory for Harrison, earning him the enduring nickname "Old Tippecanoe" and cementing his image as a valiant Indian fighter. It also significantly damaged the Native American confederacy and drove many to align with the British in the impending War of 1812.

When the War of 1812 erupted, Harrison was commissioned as a brigadier general and given command of the Army of the Northwest. His military prowess reached its zenith in October 1813 at the Battle of the Thames in Upper Canada. Leading a combined force of U.S. regulars and Kentucky militia, including the renowned frontiersman Richard Mentor Johnson, Harrison decisively defeated the British and their Native American allies. Crucially, the battle resulted in the death of Tecumseh, effectively shattering the Native American confederacy and ending the major threat to the American frontier from that direction. Harrison emerged from the war a bona fide national hero, his name synonymous with courage and triumph.

After the war, Harrison’s career transitioned fully into politics. He served terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1816-1819), the Ohio State Senate (1819-1821), and the U.S. Senate (1825-1828). His brief appointment as Minister Plenipotentiary to Gran Colombia in 1828 by President John Quincy Adams proved less successful, and he was recalled by the incoming Jackson administration. For a period, he seemed to fade from the national spotlight, living a quieter life on his farm in North Bend, Ohio.

However, the political landscape of the 1830s, dominated by the polarizing figure of Andrew Jackson and the rise of the Whig Party, offered Harrison a second act. The Whigs, a coalition united primarily by their opposition to Jacksonian democracy, desperately needed a candidate who could appeal to a broad electorate. In 1836, Harrison was one of several regional Whig candidates, losing to Jackson’s hand-picked successor, Martin Van Buren.

But it was the election of 1840 that immortalized Harrison in American political lore. The Whigs, having learned from their previous defeat, shrewdly nominated Harrison as their sole candidate. They eschewed a traditional platform, opting instead for a populist campaign that played heavily on Harrison’s military heroism and his image as a common man of the frontier, a stark contrast to Van Buren, whom they painted as an effete aristocrat living in luxury.

The famous "Log Cabin and Hard Cider" campaign was a masterstroke of political branding. When a Democratic newspaper dismissively suggested that Harrison was too old for the presidency and would be content with a log cabin and a barrel of hard cider, the Whigs seized upon it. They built miniature log cabins, distributed hard cider, and held massive rallies where supporters chanted the iconic slogan: "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!" (referring to his running mate, John Tyler of Virginia). This was the first modern campaign, characterized by rallies, parades, and a concerted effort to connect with voters on an emotional level rather than through policy debates.

The strategy worked brilliantly. In November 1840, William Henry Harrison swept to victory in a landslide, defeating Van Buren with 234 electoral votes to 60. He had achieved his lifelong ambition, becoming the ninth President of the United States.

Inauguration Day, March 4, 1841, dawned cold and blustery in Washington D.C. Defying the inclement weather and advice to wear a coat and hat, the elderly Harrison delivered the longest inaugural address in U.S. history, clocking in at nearly two hours and over 8,000 words. He spoke without a coat, hat, or gloves, exposed to the chilling winds and intermittent rain. It was an ambitious speech, outlining his vision for a limited presidency and a strong Congress, echoing Whig principles.

The rigors of the campaign and the inaugural ceremonies, coupled with the immense pressure of office seekers besieging the White House, took a toll on the 68-year-old president. Washington at the time was also known for its unsanitary conditions. Just three weeks after his inauguration, Harrison fell ill with what was initially diagnosed as pneumonia. His symptoms included a severe cold, chills, and fever. Modern historians and medical experts have debated the exact cause, with some suggesting typhoid fever contracted from the White House water supply, given the prevalent sanitation issues of the era.

Despite the efforts of his physicians, Harrison’s condition rapidly deteriorated. On April 4, 1841, exactly one month after taking the oath of office, William Henry Harrison died. His last recorded words, possibly delirious, were directed at his doctor but seemed to be for Vice President Tyler: "Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of the government. I wish them carried out. I ask nothing more."

His death sent shockwaves across the nation. He was the first American president to die in office, plunging the country into a constitutional crisis. The Constitution was vague on the issue of presidential succession, stating only that in case of the president’s "Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President." Vice President John Tyler, upon learning of Harrison’s death, firmly asserted his right to the full powers and title of the presidency, not merely to act as president. He took the oath of office, setting a vital precedent that would later be codified by the 25th Amendment. Tyler’s decisive action, though controversial at the time, ensured a smooth transition of power and avoided a potentially destabilizing vacuum in leadership.

William Henry Harrison’s legacy is, paradoxically, defined by its brevity. He had no time to implement policies, shape a political agenda, or leave a legislative mark. His presidency remains a historical footnote, a "brief candle" that burned out almost as soon as it was lit. Yet, his story is crucial. It underscores the fragility of life and the immense demands of the nation’s highest office. His death set a precedent for presidential succession, demonstrating the resilience of the American system even in unforeseen circumstances.

Moreover, his 1840 campaign revolutionized American politics, laying the groundwork for modern populist appeals and mass mobilization. He was also the grandfather of Benjamin Harrison, who would become the 23rd U.S. President in 1889, making them the only grandfather-grandson pair to hold the office.

From a Virginia aristocrat to a frontier general, a territorial governor, and finally, a president whose term was cut tragically short, William Henry Harrison’s life was a testament to ambition, courage, and the unpredictable currents of history. He may not have governed, but his death reshaped the presidency, ensuring that even in his final moments, "Old Tippecanoe" continued to influence the very fabric of the American republic.