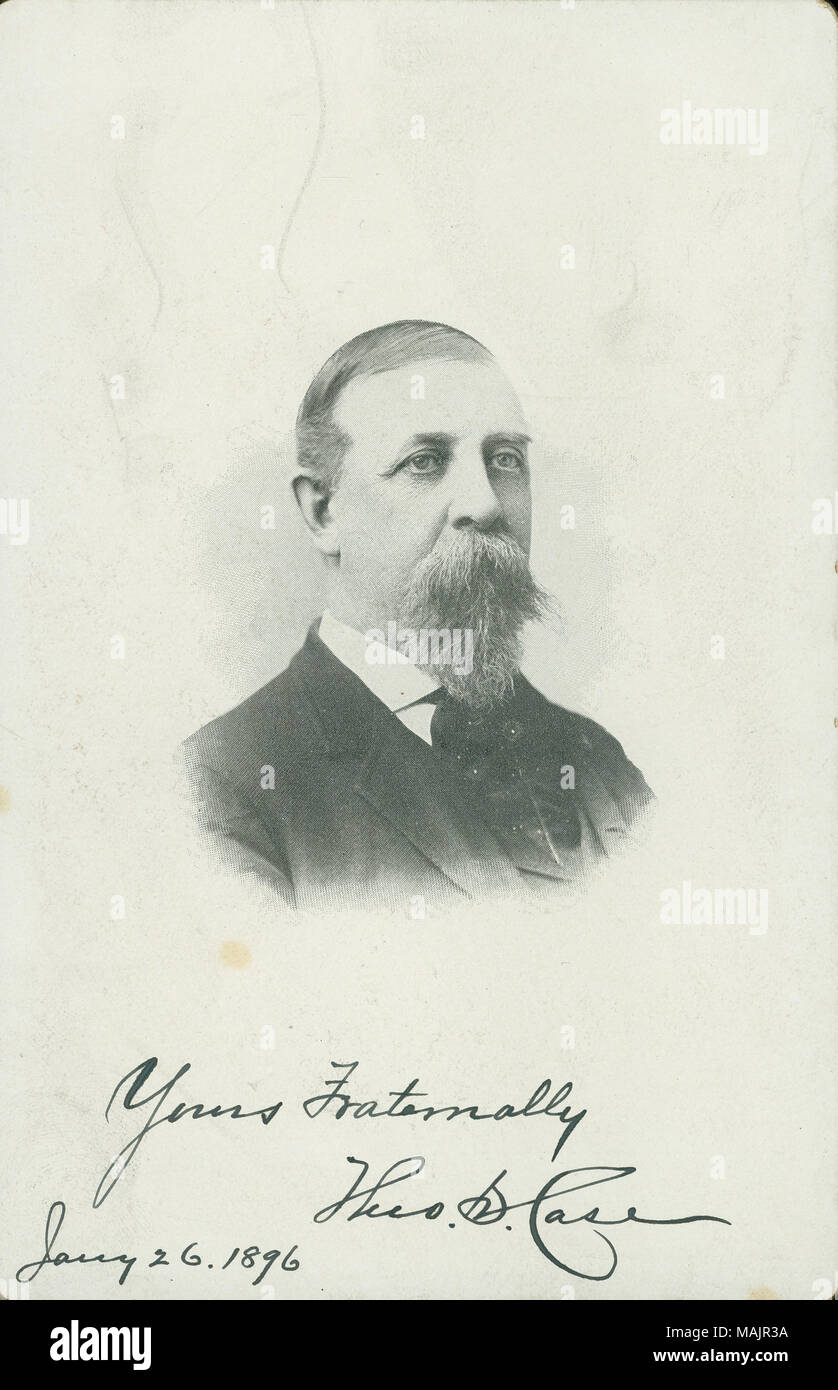

The Brilliant Eclipse: The Haunting Case of Colonel Theodore Spencer and the Shadows of 20th-Century Psychiatry

In the hallowed halls of mid-20th century American academia, few stars shone with the intellectual brilliance and poetic sensitivity of Colonel Theodore Spencer. A distinguished Harvard professor, a revered literary critic, and a poet of profound depth, Spencer was a quintessential figure of the New Criticism movement, admired by peers like T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden. Yet, beneath the glittering surface of his accomplishments lay a profound and ultimately tragic struggle with mental illness, a battle that would transform him from a vibrant intellectual into a haunting symbol of the era’s limitations in understanding the human mind. His story is not merely a personal tragedy but a poignant case study in the evolving, often brutal, landscape of psychiatric care.

Born in 1902, Theodore Spencer’s early life offered little hint of the shadows that would later consume him. Educated at Princeton, Cambridge, and Harvard, his academic career was meteoric. By 1934, he was teaching English at Harvard, quickly ascending to a full professorship. His critical work, particularly "Shakespeare and the Nature of Man" (1942), cemented his reputation as a scholar of immense insight, capable of synthesizing vast historical and literary knowledge into coherent, compelling arguments. As a poet, his collections like "The World in Your Hand" (1943) and "An Act of Life" (1944) showcased a keen intellect grappling with themes of mortality, faith, and the human condition, often with a wry, understated wit. He was, by all accounts, a man of wit, charm, and formidable intellectual energy, beloved by students and respected by colleagues.

His personal life, too, seemed stable. Married to his devoted wife, Anne, and a father, Spencer maintained a rigorous schedule of teaching, writing, and engaging with the vibrant intellectual circles of Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was a close friend and confidant of T.S. Eliot, whose own intellectual rigor and poetic sensibility mirrored Spencer’s in many ways. Eliot, in particular, held Spencer in high regard, often seeking his critical opinion and valuing his companionship. It was this very intellectual intensity, however, that perhaps masked the nascent signs of a deeper struggle.

The first subtle cracks in Spencer’s formidable intellect began to appear in the late 1940s. Colleagues and friends noticed increasing signs of anxiety, periods of disengagement, and an unsettling preoccupation with certain ideas that seemed to border on obsession. These were initially dismissed as the eccentricities of a genius, perhaps exacerbated by the pressures of academic life and the lingering anxieties of the post-war world. However, by the early 1950s, these subtle shifts escalated into unmistakable symptoms of severe mental distress.

The turning point came in 1951, culminating in a public breakdown that sent shockwaves through the Harvard community. Spencer began exhibiting overt paranoid delusions, believing he was being spied upon, that his thoughts were being manipulated, and that he was the subject of a grand, malevolent conspiracy. His behavior became increasingly erratic and disturbing, making it impossible for him to continue his teaching duties. The man who had once commanded lecture halls with his eloquent insights was now struggling to maintain a coherent grasp on reality.

The diagnosis, delivered by the psychiatric establishment of the time, was schizophrenia – a catch-all term that often encompassed a wide spectrum of severe mental illnesses, many of which are understood far more nuancedly today. In an era when psychiatric understanding was still rudimentary compared to modern neuroscience, and effective psychopharmacology was decades away, the options for treatment were limited and often drastic. For families like the Spencers, desperate to alleviate their loved one’s suffering, the prevailing medical wisdom was the only recourse.

Colonel Spencer was admitted to the Hartford Retreat, later known as the Institute of Living, a prominent private psychiatric hospital in Connecticut. What followed was a harrowing journey through the most aggressive and controversial treatments of the mid-20th century. The standard repertoire for severe mental illness included insulin coma therapy, a procedure where patients were put into a comatose state by injecting large doses of insulin, often for several hours, with the aim of "resetting" the brain. More commonly, and perhaps more infamously, was electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), then administered without muscle relaxants or anesthesia, leading to violent convulsions and often significant memory loss.

While the exact specifics of Spencer’s treatment regimen varied over the years, he undoubtedly endured repeated courses of these therapies. Records from the period, though often sparse and clinically detached, hint at the immense physical and psychological toll these interventions took. Patients often emerged disoriented, with gaps in their memory, and sometimes with personality changes that were as much a product of the treatment as the illness itself. The ultimate, and most feared, intervention was the lobotomy, a neurosurgical procedure intended to sever connections in the prefrontal cortex, often leaving patients in a docile, emotionally blunted state. While it’s not definitively known if Spencer underwent a full lobotomy, the possibility lingered for patients with his diagnosis, and other less invasive brain surgeries were sometimes performed.

The silence that often shrouded mental illness in the 1950s and 60s meant that Spencer’s long confinement was largely a private ordeal, known only to his closest family and friends. T.S. Eliot, deeply saddened by his friend’s decline, reportedly visited him at the Institute of Living, a testament to their enduring bond. These visits, however, were often painful, as Spencer, lucid at times, would sometimes present his delusions as undeniable facts, challenging Eliot’s own grasp of reality. The profound isolation, the loss of his intellectual life, and the sheer indignity of institutionalization must have been agonizing for a mind that once soared so freely.

Yet, even within the confines of the institution, glimpses of Spencer’s brilliant mind occasionally shone through the fog of illness and medication. He continued to write, albeit sporadically and often in a style marked by the fractured logic of his condition. These writings, later collected and studied, offer a poignant window into his internal world – a world where the boundaries between reality and delusion were constantly shifting, but where the desire for meaning and expression stubbornly persisted. They serve as a powerful reminder that even in severe illness, the individual’s inner life, however distorted, remains vibrant.

The "case" of Colonel Theodore Spencer became, in retrospect, a powerful, if quiet, indictment of the mid-century approach to severe mental illness. His story underscores several critical points:

-

The Limitations of Diagnosis: The broad diagnosis of "schizophrenia" in Spencer’s time likely encompassed a range of conditions that modern psychiatry differentiates more carefully. Would he have been diagnosed differently today? Could it have been a severe mood disorder, a neurological condition, or even a nuanced personality disorder exacerbated by stress? The ambiguity remains.

-

The Brutality of Treatment: The "treatments" of the era – insulin shock, high-dose ECT without modern protocols, and the specter of lobotomy – were often more akin to blunt instruments than precise medical interventions. While some patients did experience temporary relief, the long-term side effects and the sheer invasiveness were devastating. Spencer’s story is a stark reminder of how far psychiatry has, mercifully, come.

-

The Stigma of Mental Illness: The hush surrounding Spencer’s condition reflected the pervasive societal shame associated with mental illness. Unlike physical ailments, mental health issues were often seen as a moral failing or a sign of weakness, leading to isolation for both the patient and their family.

-

The Cost to Genius: Spencer’s trajectory represents the tragic loss of a brilliant mind to an illness that society was ill-equipped to manage. What further literary and critical contributions might he have made had he lived in an era with more effective treatments and greater understanding?

Colonel Theodore Spencer spent the last two decades of his life largely confined, dying in 1968 at the age of 66. His legacy, however, extends beyond his impressive academic and poetic output. His story serves as a haunting historical marker, a testament to the immense suffering caused by severe mental illness and the often misguided attempts to alleviate it.

Today, as conversations around mental health become more open, and as advancements in psychopharmacology and therapeutic approaches offer new hope, Spencer’s case stands as a powerful, if somber, reminder of a darker period. It challenges us to reflect on the ethical dimensions of treatment, the importance of compassionate care, and the continuous need for scientific inquiry to unravel the complex mysteries of the human mind. The brilliant light of Colonel Theodore Spencer’s intellect was tragically eclipsed, but his story continues to illuminate the path forward in our understanding and treatment of mental illness, ensuring that the shadows of the past might never again fall so heavily on those who suffer.