The Bullet and the Badge: The Nabor Pacheco Killing and the Shadow of Bisbee

In the sweltering Arizona summer of 1917, a nation consumed by the Great War found itself increasingly wary of internal dissent. As patriotism surged, so too did the anxieties surrounding labor unrest, particularly in industries vital to the war effort. In the copper-rich boomtown of Bisbee, Arizona, these tensions reached a bloody crescendo, culminating in an event that would forever stain the legacy of its formidable sheriff and cast a long shadow over American labor history: the killing of Nabor Pacheco by Sheriff Harry Wheeler.

This was not merely a local tragedy; it was a microcosm of a nation grappling with its identity, torn between the demands of industry, the rights of workers, and the often-brutal enforcement of "law and order" in times of perceived crisis. The story of Pacheco and Wheeler is one of power, prejudice, and the perilous price of dissent.

Bisbee: A Copper Kingdom on Edge

Bisbee, nestled in the Mule Mountains of Cochise County, was, at the turn of the 20th century, one of the richest mining districts in the world. The Copper Queen Mine, owned by the powerful Phelps Dodge Corporation, dominated the town, employing thousands of miners, many of them immigrants from Mexico and Eastern Europe. Conditions were harsh: long hours, low wages, dangerous environments, and a company that exerted near-total control over every aspect of life, from housing to commerce.

By 1917, simmering discontent had reached a boiling point. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or "Wobblies," a radical labor union advocating for "one big union" and direct action, had gained a foothold among Bisbee’s disillusioned miners. Their demands were straightforward: better wages, an eight-hour workday, safer conditions, and an end to the discriminatory "rustling card" system that blacklisted union sympathizers.

Phelps Dodge, however, was unyielding. Backed by the state and federal governments, which viewed any strike during wartime as unpatriotic and potentially treasonous, the company was determined to crush the IWW. Leading the charge against the union was Cochise County Sheriff Harry Wheeler.

Sheriff Harry Wheeler: The Iron Hand of the Law

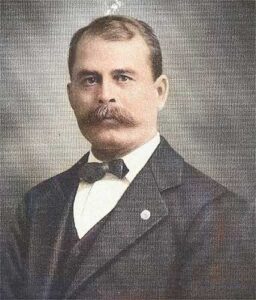

Harry Wheeler was a figure cut from the mold of the Old West – a veteran of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, a former captain in the Arizona Rangers, and a man known for his unwavering resolve and physical courage. To his supporters, he was a hero, a staunch defender of property rights and the American way of life against what they saw as anarchistic unionism. To his detractors, he was an authoritarian, a company man, and a symbol of state-sanctioned repression.

Wheeler had a deep-seated contempt for the IWW, viewing them as a threat to societal order and a front for German espionage. He famously declared, "When I see a man with an I.W.W. card, I see a man who is not for my country." This sentiment, echoed by many Bisbee residents and business owners, created a volatile atmosphere where suspicion of "outsiders" and union organizers ran rampant.

As the strike escalated in late June 1917, Bisbee became a tinderbox. Strikebreakers, often Mexican nationals, were brought in by Phelps Dodge, further inflaming tensions with the striking miners. The town was polarized, divided into those who supported the company and those who sought better conditions through the union.

The Fatal Encounter: Nabor Pacheco and the Shot Heard ‘Round Bisbee

On July 1, 1917, the simmering conflict exploded into violence. Nabor Pacheco, a young Mexican immigrant, was working as a strikebreaker for Phelps Dodge. Accounts of what transpired that day differ sharply, forming the crux of the later legal battle.

According to Sheriff Wheeler’s testimony, he and a posse of deputies were investigating a report of a man with a gun near a mine shaft. They encountered Pacheco, who Wheeler claimed was acting suspiciously and appeared to be reaching for something in his waistband. Wheeler stated that he commanded Pacheco to halt and drop what he was reaching for. When Pacheco allegedly made a sudden movement, Wheeler, fearing for his life and the lives of his deputies, fired a single shot from his revolver. The bullet struck Pacheco, killing him instantly. Wheeler maintained it was an act of self-defense, a necessary measure to neutralize a perceived threat in a highly volatile environment.

However, other witnesses, particularly those sympathetic to the miners, painted a different picture. They testified that Pacheco was unarmed, perhaps carrying a lunch pail or merely adjusting his clothing, and that he was attempting to comply with Wheeler’s orders or was even turning to flee when he was shot. Some claimed Pacheco was shot in the back. To them, the killing was an act of cold-blooded murder, an egregious abuse of power by a sheriff intent on intimidating the striking workforce.

The immediate aftermath was chaotic. Pacheco’s body was quickly removed. The incident, rather than quelling the unrest, ignited a fuse, fueling the narrative among the striking miners that the authorities and the company would stop at nothing to break the strike, even resorting to lethal force.

The Road to Deportation: A Pretext for "Order"

The killing of Nabor Pacheco became a significant piece of propaganda for those advocating for drastic measures against the IWW. Wheeler and his allies within the "Citizens’ Protective League," a vigilante organization formed by prominent Bisbee citizens and company officials, used the incident to bolster their claims that the IWW was a dangerous, lawless element that threatened the safety and stability of Bisbee. They argued that extraordinary action was necessary to restore order and protect the vital copper supply.

Less than two weeks after Pacheco’s death, on July 12, 1917, the infamous Bisbee Deportation occurred. Under the direction of Sheriff Wheeler and the Citizens’ Protective League, over 1,200 striking miners and suspected IWW sympathizers were rounded up at gunpoint, forced onto cattle cars, and deported over 200 miles into the New Mexico desert, where they were abandoned without food or water. It was an unprecedented act of mass vigilantism, carried out with the tacit approval of state and federal authorities. The "restoration of order" in Bisbee was complete, achieved through the systematic violation of civil liberties.

The Trial: Justice on Trial

Despite the overwhelming support for Wheeler among the Bisbee establishment, the killing of Nabor Pacheco could not be entirely swept under the rug. In the aftermath of the deportation, and with increasing national scrutiny of events in Bisbee, a grand jury indicted Sheriff Harry Wheeler for the murder of Nabor Pacheco.

The trial, held in Tombstone, the Cochise County seat, was a sensational affair, closely watched by the national press. The prosecution attempted to portray Wheeler as a ruthless enforcer, a man who had used excessive force against an unarmed man. They brought forward witnesses who testified to Pacheco’s compliance or retreat, and to the absence of a weapon on his person.

The defense, led by prominent local attorneys, argued vehemently for Wheeler’s self-defense. They painted Pacheco as a threatening figure, potentially armed, and emphasized the volatile environment of a wartime strike. They leveraged Wheeler’s reputation as a dedicated lawman and a patriot, framing the incident within the broader context of maintaining order against "disloyal" elements. The defense also played heavily on the prevailing anti-IWW sentiment, subtly suggesting that Pacheco, by virtue of being a strikebreaker, was involved in a dangerous situation created by the union, and that Wheeler was merely doing his duty.

The courtroom was often packed with sympathetic locals who viewed Wheeler as a hero. The jury, drawn from a community deeply affected by the strike and the prevailing anti-union sentiment, ultimately sided with the sheriff. On October 19, 1917, after a relatively short deliberation, Harry Wheeler was acquitted of the murder of Nabor Pacheco.

The verdict, while celebrated by Wheeler’s supporters as a vindication of his actions and a triumph of law and order, was met with outrage by labor activists and civil liberties advocates across the country. To them, it was a miscarriage of justice, a clear indication that in wartime Arizona, the lives of striking workers, particularly those of Mexican descent, held little value in the eyes of the law.

Legacy and Lingering Questions

The story of Nabor Pacheco and Harry Wheeler remains a potent symbol of a tumultuous era in American history. It encapsulates the fierce clash between capital and labor, the role of government in industrial disputes, and the erosion of civil liberties under the guise of national security.

Harry Wheeler, despite being acquitted of Pacheco’s murder and later escaping conviction for federal charges related to the Bisbee Deportation (the federal case was dismissed due to a lack of federal jurisdiction), remains a controversial figure. To some, he was a necessary strongman who protected his community and upheld the law in a time of crisis. To others, he was a symbol of unchecked power, a man who prioritized corporate interests over human rights, and whose actions led to the tragic death of an unarmed man and the mass violation of constitutional freedoms.

Nabor Pacheco, largely forgotten in the broader historical narrative, represents the countless nameless victims of America’s labor wars. His death, a single bullet fired on a hot July day, became a stark reminder of the deadly consequences of economic and social conflict, especially when fueled by wartime hysteria and prejudice.

The Bisbee Deportation, inextricably linked to Pacheco’s death, served as a chilling precedent, a stark warning of what could happen when the lines between law enforcement, corporate power, and vigilante justice blurred. The events of 1917 in Bisbee, and the tragic killing that preceded them, continue to provoke debate about justice, authority, and the fundamental rights of individuals in a society often defined by its economic and political struggles. The bullet that killed Nabor Pacheco echoed far beyond the copper hills of Bisbee, a haunting reminder of a nation’s complex past.