The Canyon of Conflict: Malakoff Diggins and the Birth of Environmental Law

In the quiet embrace of California’s Sierra Nevada foothills, where pine trees cast long shadows and the Yuba River whispers through ancient canyons, lies a landscape that tells a colossal story. It is a tale etched not by nature’s patient hand, but by the relentless ambition of humanity: the North Bloomfield Malakoff Diggins. What appears today as a breathtakingly vast, multi-colored canyon, a striking monument to geological forces, is in fact a man-made chasm, the largest hydraulic mining operation in the world, and the epicenter of a landmark legal battle that fundamentally reshaped American environmental law.

To understand Malakoff Diggins, one must first rewind to the mid-19th century, to the feverish chaos of the California Gold Rush. The initial easy pickings of placer gold – flakes and nuggets found in riverbeds – quickly dwindled. Miners, ever ingenious and desperate for the next big strike, turned their attention to ancient river channels buried under tons of gravel and dirt on hillsides. This gave birth to hydraulic mining, a technological marvel that promised unimaginable wealth but delivered unprecedented environmental destruction.

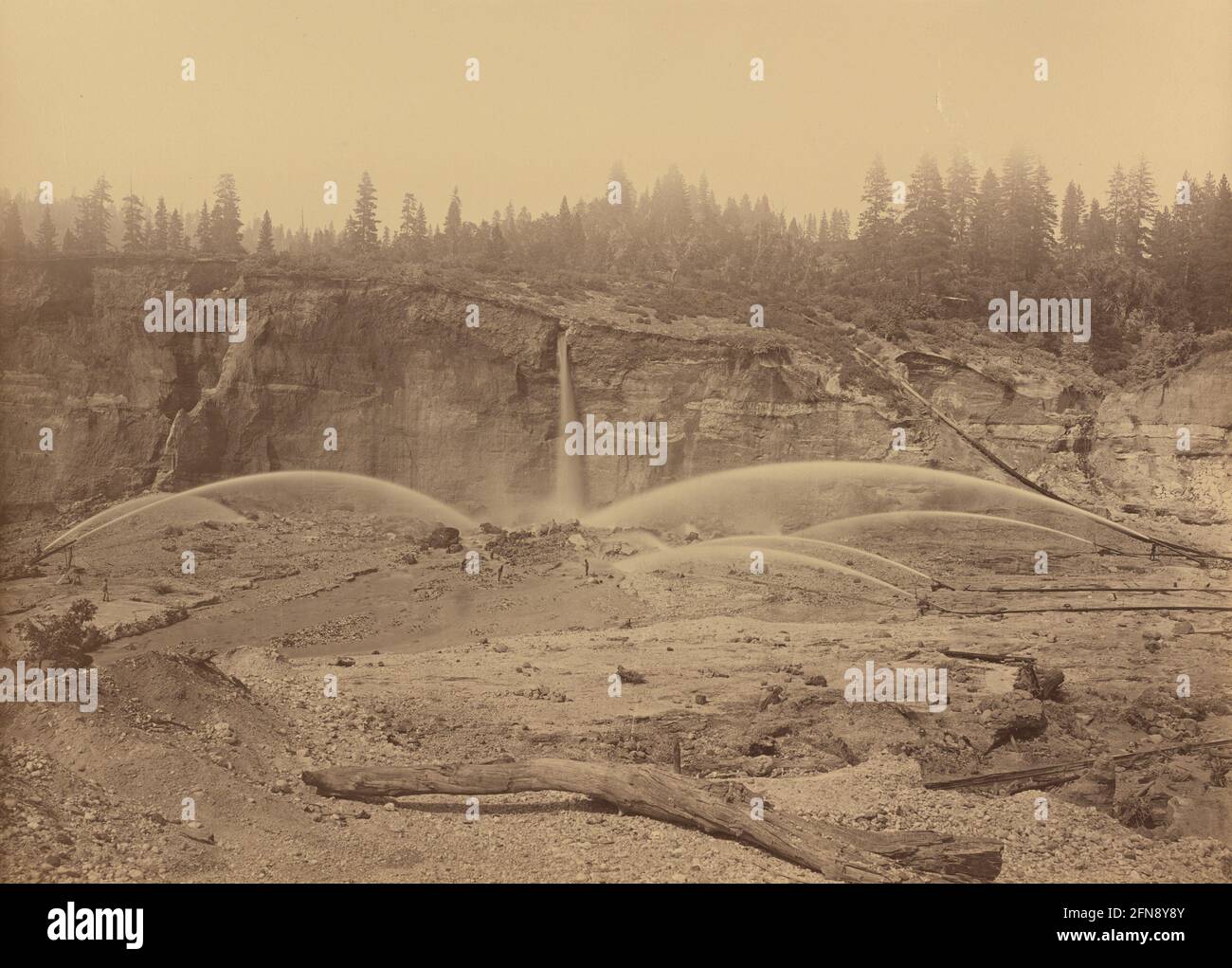

The concept was deceptively simple: harness the immense power of water. Engineers constructed elaborate systems of reservoirs, flumes, and pressurized pipes to deliver torrents of water through specialized nozzles known as "monitors" or "giants." These powerful jets, capable of tearing apart rock and soil with the force of a cannon, were directed at gold-bearing hillsides. The earth, liquefied into a muddy slurry, would then flow through sluice boxes where the heavier gold would settle, leaving behind a mountainous tide of waste.

North Bloomfield Malakoff Diggins was the undisputed king of these operations. Named, perhaps ironically, after a heavily fortified Russian tower in the Crimean War – a testament to its perceived impregnability and formidable power – Malakoff was a monstrous maw chewing through the earth. Starting in 1866, the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company, along with several smaller operations, systematically carved out a canyon that would eventually stretch over 7,000 feet long, 3,000 feet wide, and nearly 600 feet deep. To achieve this, an astonishing 1.5 billion cubic yards of earth were washed away, a volume so immense it’s difficult to conceptualize.

The engineering required was staggering. Miles of flumes, some supported by towering trestles, snaked across the landscape, diverting water from distant rivers and streams. Reservoirs held back millions of gallons, creating the necessary head pressure. Inside the Diggins, tunnels bored deep into the bedrock allowed the watery debris to exit the pit and cascade downstream. It was a testament to human ingenuity and a breathtaking display of brute force, attracting thousands of miners and transforming the remote Sierra foothills into a bustling, if temporary, industrial hub.

However, the "golden rain" that fell into the sluice boxes at Malakoff was soon matched by a "dirty rain" that fell upon the fertile agricultural lands of the Sacramento Valley, hundreds of miles downstream. The pulverized earth, clay, and gravel – collectively known as "slickens" or mining debris – did not simply disappear. It flowed into the Yuba River, then the Feather River, and finally into the mighty Sacramento River, systematically silting up riverbeds, choking navigation, and causing catastrophic floods.

Farmers, who had invested their lives and livelihoods in cultivating the rich valley soil, watched in horror as their fields were buried under feet of sterile sand and gravel. Their irrigation ditches became clogged, their homes were swamped, and their very existence was threatened. Contemporary accounts paint a grim picture: "The Sacramento River, once a clear stream, became a muddy torrent," wrote one observer, "and its tributaries, especially the Yuba, were choked with the debris of hydraulic mining to such an extent that the riverbeds were raised many feet." Navigational channels that once accommodated steamboats became impassable. Fishing grounds were destroyed as sediment smothered spawning beds.

The conflict between the powerful mining companies and the beleaguered farmers escalated into one of the most significant environmental and legal battles in American history. Initially, farmers attempted to build levees and debris dams, but these proved futile against the sheer volume of material being washed down. Their only recourse was the law.

Led by determined individuals like James H. Gooch and the newly formed Farmers’ Protective Union, a lawsuit was filed against the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company. The case, Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company, began in 1882 and quickly became a national sensation. It was a David-and-Goliath struggle, pitting the immense financial and political power of the mining industry against the collective desperation of thousands of farmers.

The trial itself was epic, lasting over two years. Witnesses testified to the devastation, engineers presented complex data on water flow and sediment transport, and lawyers passionately argued for their respective clients. The miners argued that their operations were essential for the state’s economy, representing vested property rights and contributing significantly to the national gold supply. They claimed that stopping hydraulic mining would cause economic ruin and was an infringement on their right to pursue their industry. The farmers, on the other hand, argued for the protection of their property, their livelihoods, and the public good. They asserted that the mining debris constituted a public and private nuisance that the courts had a duty to abate.

The case landed on the desk of U.S. Circuit Court Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, a man of profound legal acumen and courage. On January 7, 1884, Judge Sawyer delivered his historic verdict. He ruled in favor of the farmers, issuing a permanent injunction against the North Bloomfield Mining and Gravel Company, prohibiting the discharge of mining debris into the rivers.

Sawyer’s decision was a watershed moment, not just for California, but for the entire nation. It affirmed that private property rights, even those tied to a lucrative industry, did not supersede the rights of others to their own property, nor the public’s right to clean waterways and a functional environment. It was, in essence, the first major judicial recognition of environmental protection over industrial profit in the United States. "The rights of the farmers to cultivate their lands and to enjoy them free from this nuisance," Sawyer declared, "are as sacred as the rights of the miners to extract gold from the earth."

The impact was immediate and profound. Large-scale hydraulic mining in California, particularly in the Yuba River watershed, ground to a halt. While smaller operations continued for a time and subsequent legislation (like the Caminetti Act of 1893) attempted to regulate debris, the golden age of hydraulic mining was over. Mining towns like North Bloomfield, once bustling with thousands, rapidly declined, many becoming ghost towns.

Today, Malakoff Diggins is preserved as a California State Historic Park, a stark, beautiful, and profoundly instructive landscape. Visitors can gaze into the vast, multi-colored canyon, a geological layer cake exposed by human endeavor. They can walk through the eerie darkness of the old mining tunnels, explore the reconstructed mining town, and see the remnants of the powerful monitors. The sheer scale of the operation is still breathtaking, a testament to both human ingenuity and folly.

The park serves as a powerful reminder of the delicate balance between economic development and environmental stewardship. It illustrates how unchecked industrial practices can lead to devastating and long-lasting ecological consequences. More importantly, it stands as a monument to the power of collective action and the rule of law in addressing such challenges. The farmers who fought Woodruff v. North Bloomfield laid the groundwork for future environmental movements and established a critical precedent that continues to influence environmental legislation and jurisprudence today.

The scars on the landscape at Malakoff Diggins remain, a vibrant, silent testament to a violent past. Yet, nature is slowly reclaiming its own, with trees and shrubs softening the harsh edges of the man-made canyon. The Yuba River, though forever altered, flows clearer now. Malakoff Diggins is more than just a historical site; it is a living classroom, a dramatic tableau of conflict and resolution, a place where the echoes of giant water cannons still resonate with the quiet triumph of environmental justice. It is a powerful reminder that while the pursuit of wealth can reshape the earth, the fight for a healthy planet can, and must, prevail.