The Chains That Bound a Nation: America’s Fugitive Slave Laws and the Unraveling Union

BOSTON, MA – The chill of a May morning in 1854 did little to quell the simmering rage in Boston. Across the city, abolitionists, free blacks, and ordinary citizens watched in horror as federal marshals, backed by U.S. Marines and artillery, paraded Anthony Burns, a young man accused of being a runaway slave, through the streets. Thousands lined the route, hissing and booing, some shouting "Kidnappers!" The air crackled with defiance, but the procession continued, delivering Burns to a ship that would carry him back to the clutches of slavery in Virginia.

This was not an isolated incident. Anthony Burns was but one victim, and Boston but one battleground, in the brutal enforcement of America’s Fugitive Slave Laws – legislation that ripped at the very fabric of the nation, exposing the deep moral chasm between North and South and hurtling the country towards civil war. Far from being mere legal instruments, these laws were a federal endorsement of human bondage, transforming ordinary citizens into unwilling participants in the institution of slavery and igniting a firestorm of resistance.

The First Shackles: The 1793 Act

The concept of returning runaway slaves was woven into the very blueprint of the United States. Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, often referred to as the "Fugitive Slave Clause," mandated that "No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due."

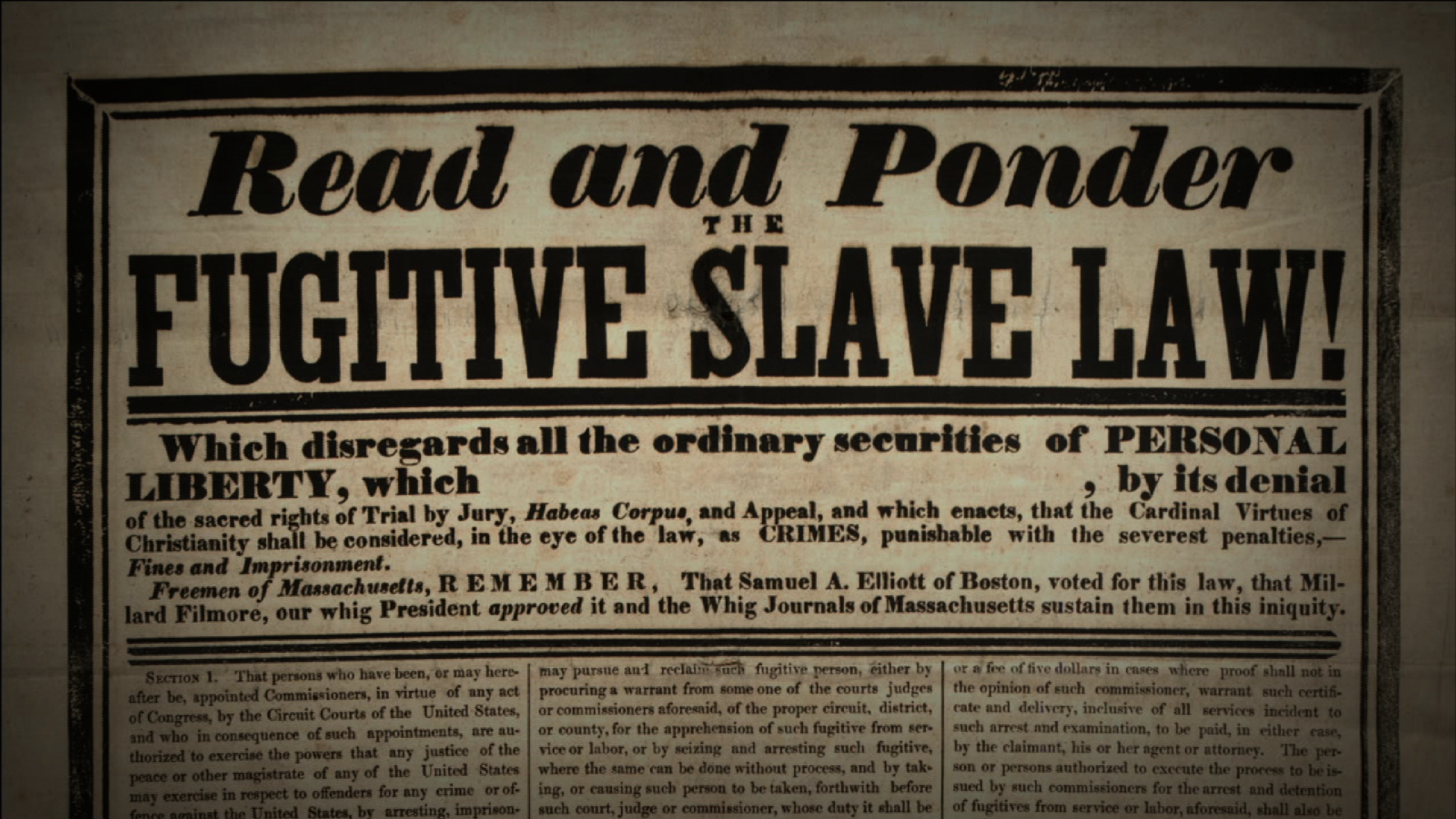

In 1793, Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Act to give this clause legal teeth. While less draconian than its successor, it nonetheless allowed slaveholders or their agents to reclaim escaped slaves simply by appearing before a federal judge or local magistrate and providing oral or written proof of ownership. The accused had no right to a jury trial or to testify on their own behalf. This initial law, however, was often weakly enforced, particularly in Northern states where anti-slavery sentiment was growing. Many states passed "personal liberty laws," designed to protect free blacks from being kidnapped under the guise of this federal statute, often by requiring jury trials for alleged fugitives or prohibiting state officials from aiding in their rendition. This patchwork of laws and varying degrees of enforcement created a simmering resentment in the South, where slaveholders felt their "property rights" were being undermined.

The "Bloodhound Bill": The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

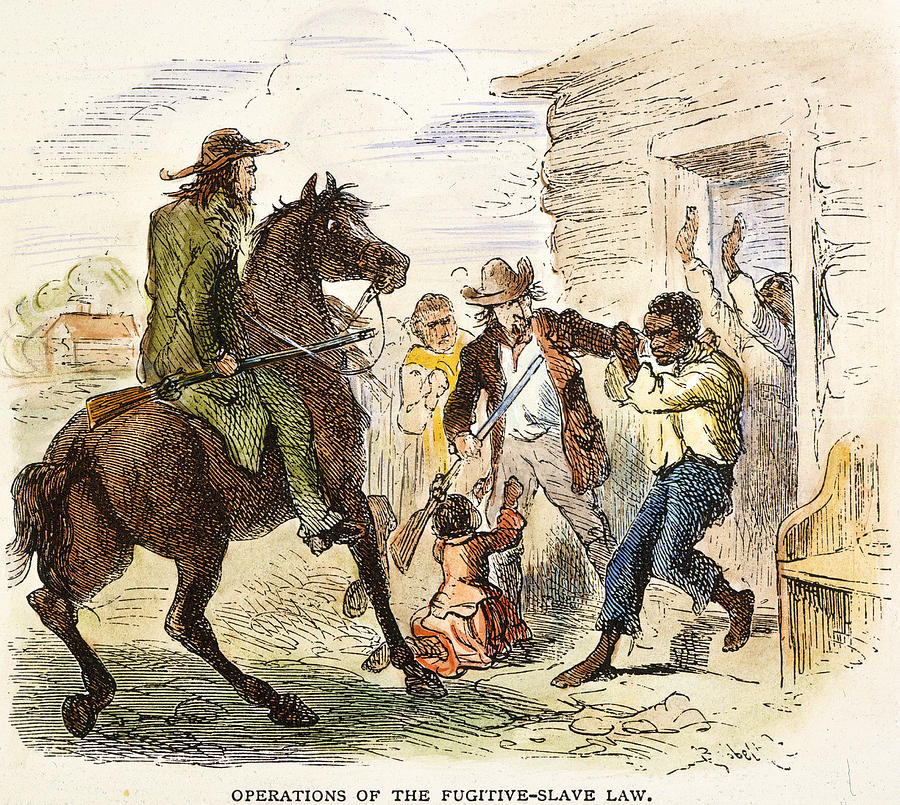

The fragile peace between North and South began to shatter in the mid-19th century, fueled by westward expansion and the question of slavery in new territories. As part of the Compromise of 1850 – a desperate attempt to avert disunion – a new, far more stringent Fugitive Slave Act was enacted. This law, often dubbed the "Bloodhound Bill" by its critics, was designed to placate the South, but it instead ignited a moral inferno in the North.

Its provisions were chillingly explicit:

- Federal Commissioners: The act established a system of federal commissioners who were empowered to hear fugitive slave cases. These commissioners were not judges and operated outside the traditional court system.

- Financial Incentive: A deeply controversial provision offered a direct financial incentive for commissioners: they received a fee of $10 if they ruled in favor of the slaveholder and sent the accused back into slavery, but only $5 if they ruled the person was free. This blatant bias effectively bribed officials to condemn.

- No Jury Trial, No Testimony: Echoing the 1793 Act, alleged fugitives were denied the right to a jury trial and could not testify on their own behalf. The only evidence required was the affidavit of the claimant.

- Compulsion of Citizens: Perhaps the most infuriating aspect for many Northerners was the provision that compelled all citizens, regardless of their personal beliefs, to assist federal marshals in capturing alleged runaways. Refusal to cooperate could result in heavy fines or imprisonment.

- Federal Enforcement: The law placed the entire weight of the federal government – its marshals, courts, and even the military – behind the apprehension and return of alleged fugitives, overriding state laws and local opposition.

This law was a direct assault on the moral conscience of the North. It brought the brutality of slavery directly into their homes, forcing them to choose between obedience to an unjust law and adherence to their own moral principles. As the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass famously declared, the law "was a hateful and horrible thing, and ought to be resisted, by every means known to freedom." He further noted, "I have no doubt that that law was one of the most effective agencies in arousing the moral indignation of the North against slavery."

The North’s Defiance: A Moral Uprising

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 backfired spectacularly on its Southern proponents. Instead of pacifying the North, it galvanized the abolitionist movement and awakened many previously indifferent citizens to the horrors of slavery.

- Increased Activity on the Underground Railroad: Harriet Tubman, the legendary "Moses of her people," redoubled her efforts. Despite the increased danger, she made numerous daring trips into the South, guiding hundreds to freedom. She once famously stated, "I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger."

- Personal Liberty Laws Strengthened: Northern states like Wisconsin and Vermont passed even more robust personal liberty laws, effectively nullifying the federal act within their borders. The Wisconsin Supreme Court, in the Ableman v. Booth case (1859), even declared the 1850 Act unconstitutional, though this was later overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

- Vigilance Committees and Rescues: Across the North, "vigilance committees" sprang up, dedicated to protecting free blacks and assisting runaways. These groups often resorted to direct action:

- The Christiana Riot (1851): In Christiana, Pennsylvania, a group of armed free blacks and abolitionists defended four alleged fugitives from a Maryland slave owner and federal marshals, resulting in the slave owner’s death and a landmark treason trial (which ended in acquittal).

- The Jerry Rescue (1851): In Syracuse, New York, a crowd of abolitionists stormed a courthouse to free William "Jerry" Henry, a cooper who had escaped from Missouri. He was spirited away to Canada.

- The Anthony Burns Case (1854): The Boston case of Anthony Burns became a national spectacle. Despite a desperate attempt by abolitionists to storm the courthouse, Burns was ultimately returned to slavery. However, the cost of his rendition was enormous – estimated at $40,000 (equivalent to over $1.4 million today) – requiring federal troops and a massive public outcry. The sight of federal bayonets enforcing slavery in a city synonymous with liberty shocked many moderate Northerners.

The law even prompted powerful literary responses. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s monumental novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was partly inspired by the horrors of the Fugitive Slave Law, particularly its impact on families. The book sold hundreds of thousands of copies and profoundly shaped public opinion.

A Legacy of Division and Disunion

While the Fugitive Slave Laws, particularly the 1850 Act, were intended to preserve the Union by appeasing the South, they had the opposite effect. They did not significantly increase the number of returned slaves (only a few hundred were officially returned out of tens of thousands who escaped), but they irrevocably hardened positions on both sides.

For the South, the inability to consistently enforce the law in the North was seen as further evidence of Northern perfidy and a fundamental disregard for Southern property rights, fueling calls for secession. For the North, the law was a stark reminder of the moral bankruptcy of slavery and the federal government’s complicity in it. It transformed a distant moral issue into a palpable, local threat, directly challenging the principles of liberty and justice that the nation ostensibly stood for.

The Fugitive Slave Laws stand as a dark testament to the compromises made at the nation’s founding, compromises that ultimately proved unsustainable. They laid bare the irreconcilable differences between two distinct visions of America – one built on the brutal foundation of human bondage, the other striving, however imperfectly, towards the ideal of universal freedom. In their aggressive enforcement, these laws didn’t just return individuals to chains; they tightened the chains of division around the entire nation, pushing it inexorably towards the cataclysm of the Civil War. The screams of Anthony Burns, echoing through Boston’s streets, were not just the cries of a man losing his freedom; they were the harbingers of a nation tearing itself apart.