The Cross and the Crown: Unveiling the Complex Lives of Spanish Missionaries

From the windswept plains of the American Southwest to the dense jungles of the Amazon, from the sun-baked deserts of Baja California to the distant islands of the Philippines, the silhouette of a Spanish mission church stands as a stark, often haunting, reminder of an audacious historical enterprise. These stone and adobe structures, with their bell towers reaching towards an unfamiliar sky, were not merely places of worship; they were the outposts of an empire, the frontier of faith, and the crucible where two worlds – European and indigenous – collided with profound and often devastating consequences.

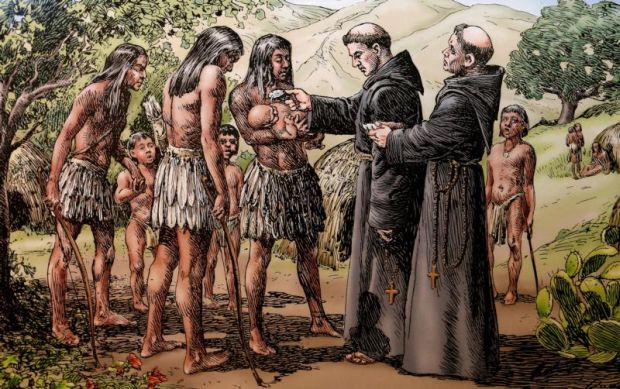

The Spanish missionary, typically a Franciscan, Dominican, or Jesuit friar, was a figure of immense paradox. Armed with a crucifix, a breviary, and an unshakeable conviction, he embarked on journeys of unfathomable peril, driven by a dual mandate: the salvation of indigenous souls and the expansion of the Spanish Crown’s dominion. This was the era of the Reconquista extended across oceans, a spiritual conquest inextricably linked to political and economic aspirations.

The Divine Mandate and Earthly Ambition

At the heart of the missionary impulse lay a fervent, often uncompromising, Catholic faith. For many friars, the New World was a vast harvest of unbaptized souls, living in what they perceived as spiritual darkness. Their primary mission, as they saw it, was to bring these people into the light of Christianity, offering them eternal salvation. This was not a passive endeavor but an active, aggressive evangelization, often characterized by the destruction of indigenous idols and the suppression of traditional spiritual practices, deemed by the missionaries as demonic.

Yet, this spiritual zeal was inextricably interwoven with the ambitions of the Spanish Crown. The Patronato Real (Royal Patronage) granted by the Pope gave the Spanish monarchs unprecedented control over the Church in the Americas. In return, the Crown funded missions, protected friars with soldiers, and viewed the spread of Christianity as a vital tool for consolidating imperial power. A converted, pacified population was easier to govern, to integrate into the colonial economy, and to defend against rival European powers. As historian Charles Gibson aptly summarized, "The Spanish conquest was not simply an economic or political phenomenon; it was also a spiritual one."

A Life of Austerity and Peril

The daily life of a Spanish missionary was one of profound austerity, relentless labor, and constant peril. Far removed from the comforts of Europe, these men often lived in rudimentary conditions, their initial "churches" sometimes little more than thatched huts. Their days were rigidly structured around prayer, mass, and the arduous tasks of building and maintaining the mission complex.

They were pioneers, agriculturalists, architects, and teachers all rolled into one. They introduced European crops like wheat, grapes, and olives, along with livestock such as cattle, sheep, and horses, fundamentally altering the landscape and economy of the regions they settled. They taught indigenous people new trades – carpentry, masonry, weaving, and blacksmithing – skills essential for the mission’s self-sufficiency. Each mission, in essence, was designed to be a miniature, self-sustaining European village, a testament to the friars’ incredible resilience and ingenuity.

But this was not a life for the faint of heart. Disease, especially smallpox, measles, and influenza, ravaged both indigenous populations and the missionaries themselves, often proving a greater killer than any weapon. The wilderness itself presented formidable challenges: harsh climates, venomous creatures, and vast, isolating distances. Communication with colonial centers or fellow friars could take months, leaving them utterly alone in their endeavors.

Moreover, relations with indigenous tribes were often fraught. While some embraced the missionaries, seeing potential benefits in their knowledge or protection, others viewed them as invaders, resisting their presence with violence. Many friars met their end at the hands of those they sought to convert, a martyrdom they often embraced as the ultimate testament to their faith. Father Junípero Serra, the Franciscan who founded the first nine missions in California, famously wrote in a letter: "Let us go forward, with the cross as our guide and the Holy Spirit as our companion." His words encapsulate the blend of faith and fortitude required for such a life.

Bridging the Linguistic Divide: A Key Tool for Conversion

One of the most remarkable, and often overlooked, aspects of missionary life was the intense effort dedicated to learning indigenous languages. Recognizing that effective evangelization required direct communication, friars immersed themselves in the complex grammars and vocabularies of Nahuatl, Quechua, Maya, Zuni, and countless other tongues. They compiled dictionaries, wrote grammars, and translated catechisms and prayers, creating the first written records for many of these languages.

This linguistic bridge was crucial for the transmission of Christian doctrine. Yet, it was also a tool of cultural transformation. By teaching indigenous peoples Spanish, and by imposing European concepts of time, morality, and social organization, the missionaries subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, undermined traditional indigenous worldviews.

The Mission System: A Double-Edged Sword

The mission system, particularly in regions like California, Texas, and Paraguay, became the primary instrument of acculturation and control. Indigenous people were encouraged, and often compelled, to live within the mission compounds, where they were educated, Christianized, and put to work. These "reducciones" or "congregaciones" were designed to civilize the "savage" and create productive members of the colonial society.

For the indigenous population, the mission experience was a profoundly ambivalent one. On the one hand, missions sometimes offered protection from hostile tribes or exploitation by Spanish soldiers and settlers. They introduced new technologies and food sources that could improve living standards. Some indigenous individuals genuinely embraced Christianity and found solace in its teachings.

On the other hand, the mission system represented a radical disruption of traditional life. Indigenous people lost their ancestral lands, their spiritual practices were suppressed, and their social structures were dismantled. They were often subjected to strict discipline, forced labor, and corporal punishment for infractions, sometimes for attempting to leave the mission. The death rate within missions was tragically high, largely due to disease, but also due to the psychological and physical stresses of forced assimilation.

Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar and one of the most vocal critics of Spanish colonial abuses, powerfully articulated the suffering of indigenous peoples. While his primary focus was on the encomienda system (a labor grant system), his writings provide a searing indictment of the often brutal realities of conquest and conversion. He wrote in "A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies" that the Spanish acted "like ravening wild beasts, wolves, tigers, and lions that have been starved for many days." While de las Casas was critiquing soldiers and settlers more directly, his words resonated with the broader impact of European presence, including the mission system’s more coercive aspects.

The Enduring Legacy and Modern Re-evaluation

Today, the legacy of Spanish missionary life remains a subject of intense debate and re-evaluation. The missions themselves, with their distinctive architecture and historical significance, are iconic landmarks. They are places of pilgrimage, tourist attractions, and vital archaeological sites that offer glimpses into a complex past. The Catholic Church in many parts of the Americas owes its very foundation to these early friars.

However, the celebratory narrative of heroic missionaries bringing civilization and salvation has been increasingly challenged by indigenous voices and contemporary historians. The focus has shifted to acknowledging the profound suffering, cultural destruction, and loss of life that accompanied the missionization process. Figures like Junípero Serra, canonized as a saint by Pope Francis in 2015, remain deeply controversial, celebrated by some for his unwavering faith and evangelistic fervor, while condemned by others as a symbol of colonial oppression and forced assimilation.

The truth, as always, lies in the nuanced grey areas between these extremes. Spanish missionaries were not monolithic figures; they were individuals with varying degrees of empathy, ambition, and understanding. Some undoubtedly believed they were acting in the best interests of indigenous peoples, even as their actions contributed to immense suffering. Others were more rigid, less compassionate, driven by a zealous conviction that brooked no compromise.

The lives of Spanish missionaries were a testament to human endurance, unwavering faith, and an often-blinding cultural certainty. They built monuments of stone and faith that endure to this day, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape and soul of the Americas. Yet, these structures also stand as silent witnesses to a clash of civilizations that forever altered the destiny of indigenous peoples, forcing us to confront the uncomfortable truths of a history where salvation and subjugation often walked hand in hand. Understanding their lives means grappling with this uncomfortable duality, acknowledging both the cross they carried and the crown they served, and the enduring, complex legacy they bequeathed to the world.