The Crucible of Corinth: A Desperate Gamble for the Western Theater

In the autumn of 1862, as the American Civil War raged with escalating ferocity, a vital railroad junction in northeastern Mississippi became the focal point of a desperate Confederate gamble to reclaim the initiative in the Western Theater. The Iuka-Corinth Campaign, a series of sharp engagements culminating in the brutal Second Battle of Corinth, was a bloody and pivotal struggle for control of the Confederacy’s economic lifelines, a contest that would ultimately shape the strategic landscape for the remainder of the war. It was a campaign marked by bold Confederate ambition, Union resilience, tactical blunders, and immense human cost, a true crucible for the commanders and the fighting men involved.

The Strategic Prize: Corinth

Corinth, Mississippi, was more than just a town; it was a strategic lynchpin. Here, the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, running north-south, intersected with the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, a crucial east-west artery connecting the Mississippi River to the Atlantic seaboard. Control of Corinth meant control over vital supply lines, troop movements, and the economic backbone of the Deep South. After the costly Union victory at Shiloh in April 1862, Federal forces under Major General Henry W. Halleck had painstakingly advanced on and captured Corinth, forcing a Confederate evacuation. This had been a significant blow to the Confederacy, and regaining it became an imperative.

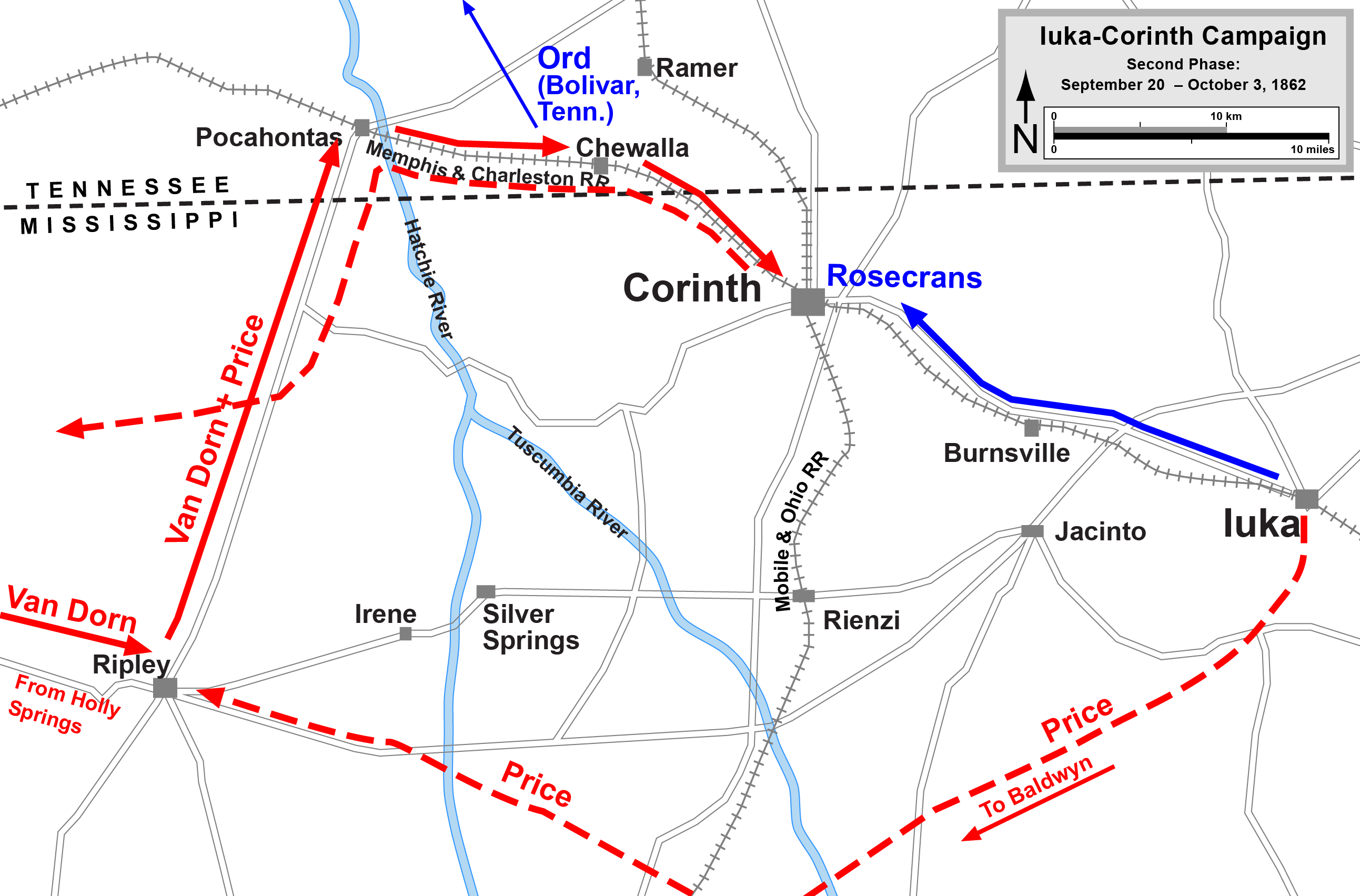

By late summer, the Union command in the region was fragmented. Major General Ulysses S. Grant commanded the District of West Tennessee, headquartered at Jackson, while Major General William S. Rosecrans led the Army of the Mississippi, holding Corinth itself. The Confederates, meanwhile, under the flamboyant and often reckless Major General Earl Van Dorn, commanding the Army of West Tennessee, envisioned a grand offensive. His plan was audacious: unite with Major General Sterling Price’s veteran "Army of the West" from northeastern Mississippi, then strike north to recapture Corinth, and potentially even advance into Middle Tennessee, severing Union supply lines and relieving pressure on other Confederate fronts.

Iuka: A Prelude of Missed Opportunities

The first act of this drama unfolded around the small town of Iuka, east of Corinth. Price, a former Missouri governor and Mexican-American War veteran, moved his 14,000-strong force towards Iuka in early September, aiming to capture Union supplies and disrupt Rosecrans’s communications. Grant, anticipating Price’s movements, dispatched Rosecrans with approximately 9,000 men to approach Iuka from the southwest, while Major General Edward O.C. Ord, with another 8,000, was to strike from the northwest, trapping Price.

On September 19, 1862, Rosecrans’s forces unexpectedly collided with Price’s Confederates just outside Iuka. The resulting battle was fierce and concentrated. The terrain, densely wooded and broken, made coordinated movements difficult. For nearly four hours, the two sides slugged it out, often at close quarters. Price’s Confederates, particularly his Missourians, fought with their characteristic tenacity, repeatedly attacking the Union lines. Rosecrans’s men, however, held their ground with equal determination.

Crucially, Ord’s column, which was supposed to attack simultaneously, never engaged. Grant, stationed with Ord, famously stated that he could not hear the sounds of Rosecrans’s battle, a claim later disputed by many. Whether due to atmospheric conditions, miscommunication, or Grant’s own caution, the Confederate escape route remained open. Under the cover of darkness, Price skillfully disengaged his forces and slipped away, marching south to link up with Van Dorn. The Battle of Iuka, though a tactical draw, was a strategic failure for the Union, as Price’s escape allowed the Confederate offensive to continue. Casualties were significant, with Union losses around 790 and Confederate losses exceeding 1,500.

The Gathering Storm: Van Dorn’s Grand Design

Price successfully united his forces with Van Dorn’s in the Tupelo area, forming an army of roughly 22,000 men. Van Dorn, known for his dash and aggressive spirit but also his penchant for taking risks, was now ready to execute his ambitious plan. He intended a direct assault on Corinth. His intelligence suggested that Rosecrans’s garrison was smaller than it actually was, and he believed a swift, decisive blow could overwhelm the Union defenses.

Rosecrans, a devout Catholic known for his eccentricities and tactical acumen, was no fool. He correctly deduced Van Dorn’s objective. Realizing his position was exposed, he pulled his forces back into Corinth, strengthening the elaborate defenses that Halleck’s army had constructed months earlier. These included two lines of fortifications: an outer line of earthworks and abatis (felled trees with sharpened branches), and an inner, stronger line closer to the town center, protected by artillery redoubts and rifle pits. Rosecrans deliberately left gaps in the outer line, hoping to lure the Confederates into a killing zone where they would be exposed to converging Union fire.

Corinth: The Bloody Harvest

The Confederate advance began on October 3, 1862. Van Dorn’s plan called for a two-pronged attack, with Price’s corps on the left and Major General Mansfield Lovell’s corps on the right. The day dawned hot and dusty, adding to the exhaustion of the marching Confederates. As they approached Corinth, they immediately encountered the Union’s outer defenses. The fighting began around 10:00 AM.

The Confederates, brimming with initial confidence, pushed hard. Price’s men, veterans of Iuka, drove back the Union skirmishers and then crashed into the main Union outer line. The fighting was intense and often hand-to-hand. The Union troops, under commanders like Brigadier General David S. Stanley and Brigadier General Charles S. Hamilton, fiercely resisted. Lovell’s corps on the right also met stiff opposition, struggling through the abatis and under heavy artillery fire.

Throughout the afternoon, the battle ebbed and flowed. The Confederates, despite heavy losses, slowly gained ground, pushing the Union forces back from the outer works towards the inner defensive perimeter. By evening, Van Dorn believed he had the advantage. His troops were exhausted but buoyed by their perceived success. However, the Confederates had paid a terrible price for their advances, and Rosecrans’s men were now concentrated in their strongest positions. As night fell, the sounds of battle gave way to the cries of the wounded and the grim preparations for the next day.

October 4 dawned clear and cool, but the air was thick with tension. Van Dorn, convinced that one more desperate push would shatter the Union lines, ordered a full-scale assault on the inner defenses. His plan was simple: a frontal charge directly into the heart of Corinth. It was a gamble of immense proportions.

Around 9:00 AM, the Confederate wave surged forward. Price’s corps, particularly the Missourians and Texans, launched themselves with incredible bravery against the Union center. They faced a murderous fire from Battery Robinett and Battery Powell, artillery redoubts that commanded the approaches to the town square, as well as volleys from infantry sheltered in rifle pits and behind barricades.

In a scene of unbelievable ferocity, some Confederates actually breached the Union lines. They surged past Battery Powell, through the town, and into the very streets of Corinth, even briefly reaching Rosecrans’s headquarters. Eyewitnesses described the sheer chaos: "The Rebels came yelling like devils incarnate," wrote one Union soldier, "but we met them with a storm of lead." Another recalled the ground "strewn with the dead and dying like leaves after an autumn gale."

However, the penetration was fleeting. Rosecrans, exhibiting coolness under fire, quickly organized a counterattack. Union reserves were rushed forward, plugging the gaps and launching ferocious bayonet charges. The Confederates, exhausted, decimated, and disoriented by the unexpected resistance within the town, were met with overwhelming force. They faltered, then broke, retreating in disarray. Lovell’s assault on the right flank also failed to make significant headway against the well-entrenched Union defenders.

The Retreat and Pursuit

The Confederate army, shattered and demoralized, began a desperate retreat southward. Van Dorn’s grand gamble had failed spectacularly. Rosecrans, initially slow to organize a pursuit, eventually sent his cavalry and infantry after the retreating Confederates. The pursuit, however, was not as aggressive as many in the Union high command desired, earning Rosecrans some criticism.

The retreating Confederates faced further hardship. At the Battle of Hatchie’s Bridge (October 5), a Union force under Ord and Major General Stephen A. Hurlbut intercepted Van Dorn’s column. While the Confederates managed to escape, they suffered additional casualties and lost valuable equipment. Van Dorn eventually led his battered army back to Ripley, Mississippi, having lost nearly 4,800 men killed, wounded, or captured in the Corinth campaign. Union losses, though heavy, were significantly less, around 2,500.

Aftermath and Significance

The Iuka-Corinth Campaign was a decisive Union victory. It secured the crucial railroad junction of Corinth for the Federal forces, effectively ending any serious Confederate threat to West Tennessee for the remainder of the war. It shattered Van Dorn’s army and his reputation, and it solidified Union control over a vital part of the Western Theater, paving the way for Grant’s eventual Vicksburg Campaign.

For Rosecrans, the victory was a moment of triumph, though his slow pursuit invited censure. He was soon transferred to command the Army of the Cumberland, where he would continue to play a significant, albeit ultimately tragic, role in the war. For Grant, though criticized for Iuka, the overall success of the campaign under his departmental command further burnished his growing reputation as a tenacious and strategic leader.

The fields around Iuka and Corinth were stained crimson, a testament to the brutal cost of the struggle. The campaign underscored the strategic importance of railroads in the Civil War and highlighted the courage and sacrifice of soldiers on both sides. It was a desperate gamble that failed, but one that left an indelible mark on the landscape of the Western Theater and on the long, bloody road to Union victory. The crucible of Corinth proved too hot for the Confederates, their ambitions melting away under the relentless fire of Union defense.