The Crucible of Freedom: Abolitionists and the Bleeding Kansas Struggle

In the vast, untamed heartland of America, a fierce and bloody ideological war erupted in the mid-19th century, transforming the nascent territory of Kansas into a crucible of the nation’s deepest moral and political divides. This was "Bleeding Kansas," a period of intense conflict from 1854 to 1859, where the very soul of the republic – whether it would be free or slave – was contested with ballots, legislation, and, ultimately, bloodshed. At the heart of this struggle stood the abolitionists, a diverse group of men and women driven by a fervent belief in human liberty, who risked everything to ensure that Kansas would enter the Union as a free state.

The stage for this conflict was set by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. This seemingly innocuous piece of legislation aimed to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opening them for westward expansion and a transcontinental railroad. However, its fatal flaw, and its revolutionary impact, lay in its embrace of "popular sovereignty." This doctrine stipulated that the residents of each territory, rather than Congress, would decide whether to permit slavery within their borders. It effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, thus throwing open vast new territories to the institution of slavery and igniting a firestorm across the nation.

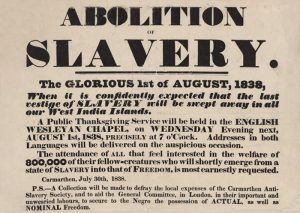

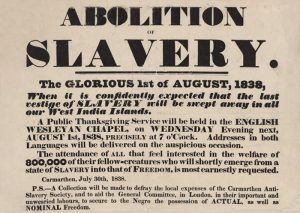

For abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was an outrage, a betrayal of long-standing agreements, and a direct threat to the moral fabric of the nation. They saw it as a desperate attempt by the "Slave Power" – a perceived conspiracy of Southern slaveholders – to expand their dominion. In response, a powerful and organized movement emerged to ensure that Kansas would vote for freedom.

One of the most instrumental forces in this early phase was the New England Emigrant Aid Company, founded by Eli Thayer. This organization was not merely a humanitarian effort; it was a calculated and strategic venture to populate Kansas with anti-slavery settlers. The company provided financial assistance, discounted travel, and even pre-fabricated housing kits to thousands of New Englanders willing to stake their claim and their vote for freedom in the distant territory. Their mission was clear: to outnumber pro-slavery settlers and secure Kansas for the free-state cause through democratic means.

These emigrants, often dubbed "Free-Staters," were a diverse lot. Some were ardent abolitionists, driven by a deep moral conviction that slavery was a sin. Others were "free-soilers," more concerned with economic opportunity and preventing the competition of slave labor, believing that slavery degraded white labor. Regardless of their specific motivations, they shared a common goal: to prevent slavery from taking root in Kansas. They established towns like Lawrence, named after Amos A. Lawrence, a prominent benefactor of the Emigrant Aid Company, which quickly became a bastion of anti-slavery sentiment and a symbol of Free-State resistance.

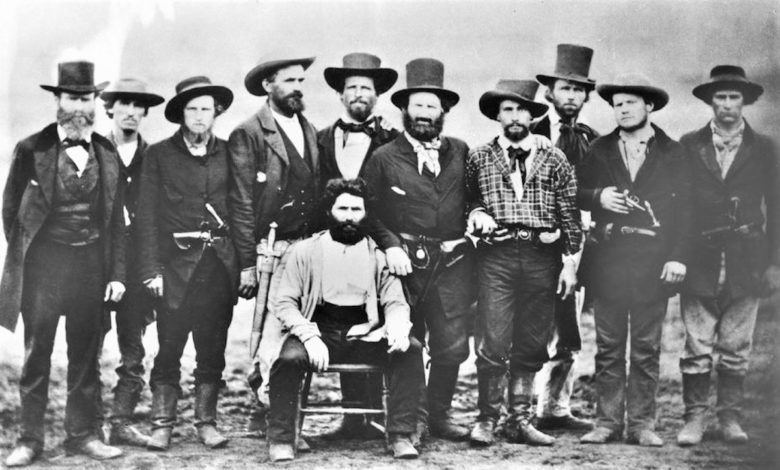

However, the pro-slavery forces were equally determined. Across the border in Missouri, fiercely pro-slavery settlers, known as "Border Ruffians," led by figures like Senator David Rice Atchison, viewed the New England influx with alarm and hostility. They saw Kansas as a natural extension of Missouri and essential for the security of their slave property. Atchison famously declared, "We are going to extend the institutions of Missouri over the territory, at the point of the bowie knife and revolver." They crossed into Kansas, often armed, to vote illegally in territorial elections, intimidate Free-State settlers, and enforce their will through violence.

The first territorial elections were notoriously fraudulent. In March 1855, thousands of Border Ruffians poured across the Missouri border, cast illegal ballots, and secured a pro-slavery majority in the territorial legislature. This body, meeting in Lecompton, promptly enacted a draconian slave code, including provisions that made it a capital offense to aid an escaped slave and a felony to even speak or write against slavery.

The Free-Staters refused to recognize this "bogus legislature." They formed their own government, drafted the Topeka Constitution (which prohibited slavery), and elected their own governor, Charles Robinson, a shrewd and pragmatic leader from Massachusetts who had been instrumental in organizing the Free-State movement. Kansas now had two rival governments, two constitutions, and two fiercely opposed visions for its future, setting the stage for direct confrontation.

The tension simmered, then boiled over. The first major act of violence was the Sacking of Lawrence on May 21, 1856. A pro-slavery posse, led by Sheriff Samuel J. Jones, rode into Lawrence, ostensibly to execute warrants. Instead, they destroyed the Free-State hotel, ransacked homes, and demolished the printing presses of two anti-slavery newspapers. While no lives were lost, the destruction was a clear message of intimidation and a profound insult to Free-State pride.

Just days later, a far more brutal act of retaliation occurred. John Brown, a fervent abolitionist and deeply religious man who believed he was an instrument of God’s wrath, arrived in Kansas with several of his sons. Haunted by the suffering of enslaved people and enraged by the Sacking of Lawrence, Brown led a small band of men to Pottawatomie Creek on the night of May 24-25, 1856. In a horrific act of vigilante justice, they dragged five pro-slavery settlers from their homes and hacked them to death with broadswords in front of their families. Brown justified his actions as necessary to "strike terror" into the hearts of pro-slavery forces and demonstrate that violence would be met with violence.

The Pottawatomie Massacre sent shockwaves through the territory and across the nation. It marked a terrifying escalation of the conflict, ushering in an era of guerrilla warfare. John Brown became a reviled figure to many, but a martyr and hero to some radical abolitionists. His actions, though deeply controversial, highlighted the desperate and often brutal nature of the struggle for Kansas.

The violence continued throughout 1856. Skirmishes, raids, and retaliatory killings became commonplace. In August, Brown led Free-State forces in the Battle of Osawatomie, defending the town against a larger pro-slavery force. Though outnumbered and eventually forced to retreat, Brown’s fierce resistance earned him the nickname "Osawatomie Brown" and further cemented his legend.

The national spotlight intensified on Kansas. Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune and other Northern newspapers published harrowing accounts of the violence, often painting the Free-Staters as heroic defenders of liberty against tyrannical "ruffians." Conversely, Southern newspapers decried the "abolitionist fanatics" and their murderous tactics. The conflict became a proxy war, drawing in resources and volunteers from both North and South. Henry Ward Beecher, a prominent abolitionist minister and brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, famously raised money to send Sharps rifles to Free-State settlers, jokingly referring to them as "Beecher’s Bibles," implying that rifles were as vital as scripture in the fight against slavery.

Despite the chaos, the Free-Staters continued their political fight. They rejected the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, which, even with a fraudulent vote, narrowly failed to pass Congress due to the impassioned opposition of Douglas himself, who realized it violated the spirit of popular sovereignty. This political battle further fractured the Democratic Party, a crucial precursor to the 1860 election.

It wasn’t until 1859 that a constitution, the Wyandotte Constitution, was finally drafted and approved by the people of Kansas that explicitly prohibited slavery. This constitution, largely the work of Free-State delegates, finally paved the way for Kansas’s admission to the Union as a free state on January 29, 1861, just weeks before the outbreak of the Civil War.

The abolitionists in Kansas, from the organized efforts of the New England Emigrant Aid Company to the radical violence of John Brown, played an indispensable role in shaping the territory’s destiny. Their determination, their willingness to sacrifice, and their unwavering belief in freedom transformed Kansas into a battleground for the future of the nation. "Bleeding Kansas" demonstrated that the issue of slavery could not be contained by political compromise; it would demand a reckoning. The violence in Kansas was a chilling rehearsal for the Civil War, teaching both sides the brutal realities of armed conflict and solidifying the irreconcilable differences that would soon tear the nation apart.

The legacy of the abolitionists in Kansas is complex, marked by both principled courage and unsettling violence. Yet, their struggle ultimately ensured that the Sunflower State would enter the Union under the banner of freedom, a testament to their enduring fight against what they believed was the greatest moral evil of their time. Their actions, though controversial, indelibly etched Kansas into the annals of American history as a crucible where the ideals of liberty and equality were forged in fire and blood.