The Crucible of Indian Territory: Oklahoma’s Unsung Civil War

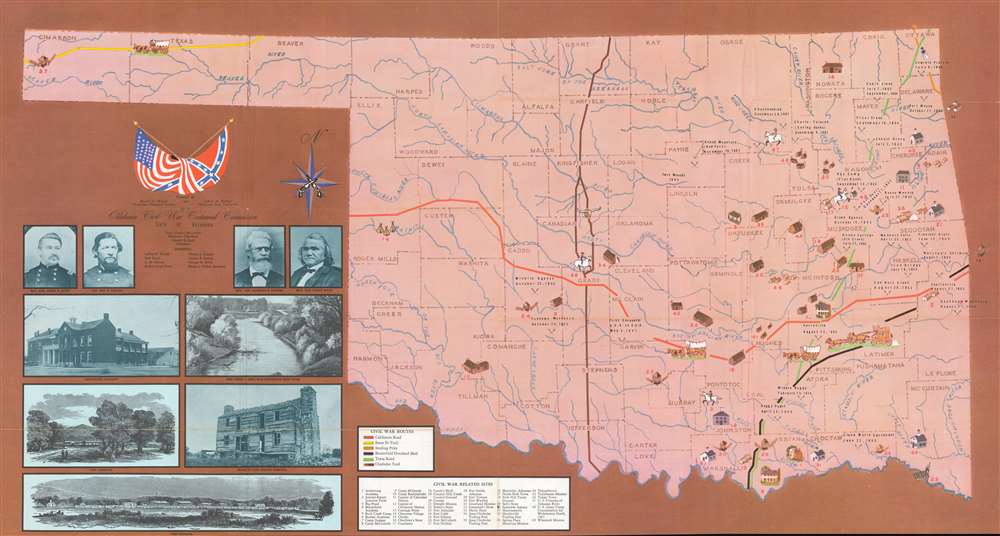

While the American Civil War raged across battlefields like Gettysburg and Vicksburg, a different, equally brutal conflict unfolded in the vast, untamed lands of what was then known as Indian Territory – present-day Oklahoma. Far from the grand armies of the East, this was a war of desperate choices, fractured loyalties, and profound devastation, fought by Native American nations caught in the maelstrom of a white man’s war. Often overlooked in the broader narrative of the conflict, the struggle in Indian Territory was unique, devastating, and fundamentally reshaped the destiny of its indigenous inhabitants.

At the war’s outset in 1861, Indian Territory was not a state, but a collection of sovereign nations – primarily the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, collectively known as the "Five Civilized Tribes." These nations had been forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States during the infamous Trail of Tears, resettled in this new domain with solemn promises of perpetual sovereignty from the U.S. government. However, these promises proved as fragile as the treaties themselves when the Union fractured.

The tribes were not monolithic entities; they were complex societies with internal divisions, economic interests, and historical grievances. Many had adopted aspects of Southern culture, including large-scale farming and, crucially, chattel slavery. This economic and cultural affinity with the South, coupled with lingering resentment over the U.S. government’s broken treaties and the trauma of removal, made the Confederacy an attractive, if not inevitable, ally for some.

The Southern Embrace and Fractured Loyalties

The Confederate government, quick to recognize the strategic importance of Indian Territory – a buffer between Kansas and Texas, and a potential source of troops and resources – dispatched Arkansas Commissioner Albert Pike to negotiate treaties. Pike promised the tribes not only protection but also recognition of their sovereignty, financial annuities, and even seats in the Confederate Congress. These were powerful inducements, especially compared to the distant and often neglectful U.S. government.

The Choctaw and Chickasaw nations, with their strong ties to Southern culture and significant slaveholding populations, were among the first to side with the Confederacy, signing treaties in the summer of 1861. Their principal chiefs, like Douglas H. Cooper of the Choctaw and Winchester Colbert of the Chickasaw, enthusiastically embraced the Southern cause.

The Cherokee Nation, the largest and most politically sophisticated, faced a deeper internal schism. Principal Chief John Ross, a shrewd politician who had initially advocated for neutrality, found his position increasingly untenable. The nation had long been divided between his traditionalist faction and the Treaty Party, led by Elias Boudinot and Stand Watie, who had supported removal and now leaned heavily towards the Confederacy. Watie, a brilliant military strategist, quickly raised a regiment of Cherokee Mounted Rifles for the South. Under immense pressure, and with Confederate troops occupying parts of the territory, Ross ultimately signed a treaty with the Confederacy in October 1861.

However, not all Cherokees, nor all members of the other tribes, accepted this alliance. Many full-bloods, traditionalists, and those who remembered the Trail of Tears as a betrayal by white Americans, remained fiercely loyal to the Union. Among the Creek, this sentiment coalesced around the venerable Chief Opothleyahola.

Opothleyahola’s Odyssey and the Refugee Crisis

Opothleyahola, an elder Creek chief and a staunch Unionist, refused to acknowledge the Confederate treaties. He gathered thousands of Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and even some enslaved African Americans who sought freedom, forming a large exodus of loyalists. Their goal was Kansas, where they hoped to find refuge and Union protection.

This desperate trek, beginning in late 1861, became known as the "Loyalist Flight." Pursued by Confederate forces led by Colonel Douglas H. Cooper and Stand Watie, Opothleyahola’s followers fought a series of desperate skirmishes – Round Mountain, Chusto-Talasah, and Chustenahlah – often referred to as the "Trail of Blood on the Ice." Ill-equipped, starving, and battling the harsh winter elements, thousands perished from disease, exposure, and combat. Those who reached Kansas arrived as destitute refugees, their suffering a stark testament to the brutality of the conflict and the U.S. government’s initial failure to protect its loyal Native allies. The federal government’s slow response to their plight deepened the sense of betrayal felt by many.

The War Itself: Guerrilla Warfare and Major Engagements

The conflict in Indian Territory was largely a war of attrition, characterized by relentless guerrilla warfare, bushwhacking, and raids rather than large-scale pitched battles. Supply lines were long, and the vast, sparsely populated terrain made conventional warfare difficult. Bands of raiders, often composed of mixed-blood and white outlaws, roamed the territory, plundering, burning, and killing with impunity. "Brother fought brother, and neighbor fought neighbor," as the saying goes, but here it was literal, with tribal members often facing their own kin across the battlefield.

Despite the prevalence of guerrilla tactics, two significant conventional battles stand out:

-

The Battle of Honey Springs (July 17, 1863): Often called the "Gettysburg of the West," this was the largest and most decisive battle fought in Indian Territory. Union forces, composed of white, African American (including the famed 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, one of the first black regiments to see combat), and Native American troops (including the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Indian Home Guard Regiments, composed of Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee loyalists), under the command of Major General James G. Blunt, decisively defeated Confederate forces led by Douglas H. Cooper. The Union victory secured control of much of Indian Territory north of the Arkansas River, disrupted Confederate supply lines, and boosted Union morale among the Native Americans. It also demonstrated the combat effectiveness of African American and Native American soldiers.

-

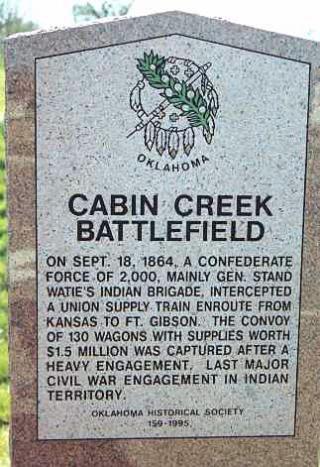

The Second Battle of Cabin Creek (September 19, 1864): This battle showcased the tactical brilliance of Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie. Leading a combined force of Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Choctaw troops, Watie ambushed a large Union supply train at Cabin Creek. The Confederates captured hundreds of wagons, thousands of horses and mules, and a vast amount of supplies, dealing a significant blow to Union operations and demonstrating the continued Confederate threat in the region, even as the war wound down elsewhere. This was one of the last major Confederate victories in the Trans-Mississippi theater.

Stand Watie, the only Native American to achieve the rank of brigadier general in the Confederate army, became a legendary figure. His Cherokee Mounted Rifles were highly effective and tenacious fighters, renowned for their daring raids and adaptability. Watie was also the last Confederate general to formally surrender, doing so on June 23, 1865, more than two months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. "I have done the best I could," he is famously quoted as saying upon his surrender, a testament to his unwavering commitment to the Confederate cause and his people.

Devastation and a Bitter Legacy

The impact of the Civil War on Indian Territory was catastrophic. The land was ravaged, farms and homes were burned, and livestock was slaughtered or stolen. The social fabric of the tribes was torn apart by internal divisions, economic ruin, and the loss of life. An estimated one-third of the Cherokee population perished during the war, and other tribes suffered similarly heavy losses. Many survivors faced destitution and displacement.

The war also served as a convenient pretext for the U.S. government to further erode tribal sovereignty. Despite the fact that many tribal members had remained loyal to the Union, the federal government deemed all the Five Civilized Tribes "rebellious" for their initial Confederate alliances. The Reconstruction Treaties of 1866 imposed harsh penalties, including significant land cessions (which paved the way for white settlement), the abolition of slavery within the tribes, and the requirement to grant freedpeople tribal citizenship. These treaties further diminished tribal lands and autonomy, setting the stage for the eventual dissolution of tribal governments and the forced allotment of lands in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in Oklahoma statehood in 1907.

The Civil War in Indian Territory was not merely a side-show to the main conflict; it was a central, defining event for the Native American nations involved. It highlighted the precarious position of indigenous sovereignty in the face of expansionist pressures, the devastating consequences of being caught between warring white factions, and the enduring resilience of people fighting for their homes, cultures, and futures. It remains a stark reminder that the American Civil War was far more complex and far-reaching than is often remembered, a truly national conflict that spared no corner of the divided republic, and left an indelible mark on the land and peoples of what would become Oklahoma.