The Crucible of Progress: Forging Modern America in the Industrial Progressive Era

New York City, 1900. The air hung thick with the acrid scent of coal smoke, mingling with the exhaust of horse-drawn carriages and the faint, metallic tang of new industry. Towering steel skyscrapers, symbols of unprecedented wealth and ambition, clawed at a sky often obscured by the grime of progress. Below, the streets teemed with a kaleidoscope of humanity: fresh-faced immigrants clutching their dreams, factory workers with weary eyes, and the opulent elite in their finery. This was America at the dawn of the 20th century, a nation simultaneously intoxicated by its industrial might and deeply troubled by its profound social inequities. This was the Industrial Progressive Era – a tumultuous, transformative period when the very soul of the nation was forged in the crucible of innovation and reform.

Spanning roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s, this era was a direct consequence of the Second Industrial Revolution. Factories churned out goods at an unimaginable pace, railroads crisscrossed the continent, and new technologies like electricity and the automobile began to reshape daily life. Titans of industry – Andrew Carnegie in steel, John D. Rockefeller in oil, J.P. Morgan in finance – amassed fortunes that dwarfed those of European royalty, creating vast monopolies and trusts that concentrated economic power in the hands of a few. This unfettered capitalism, while propelling America onto the global stage, also birthed a host of profound social ills.

The Shadow of Prosperity: A Nation in Distress

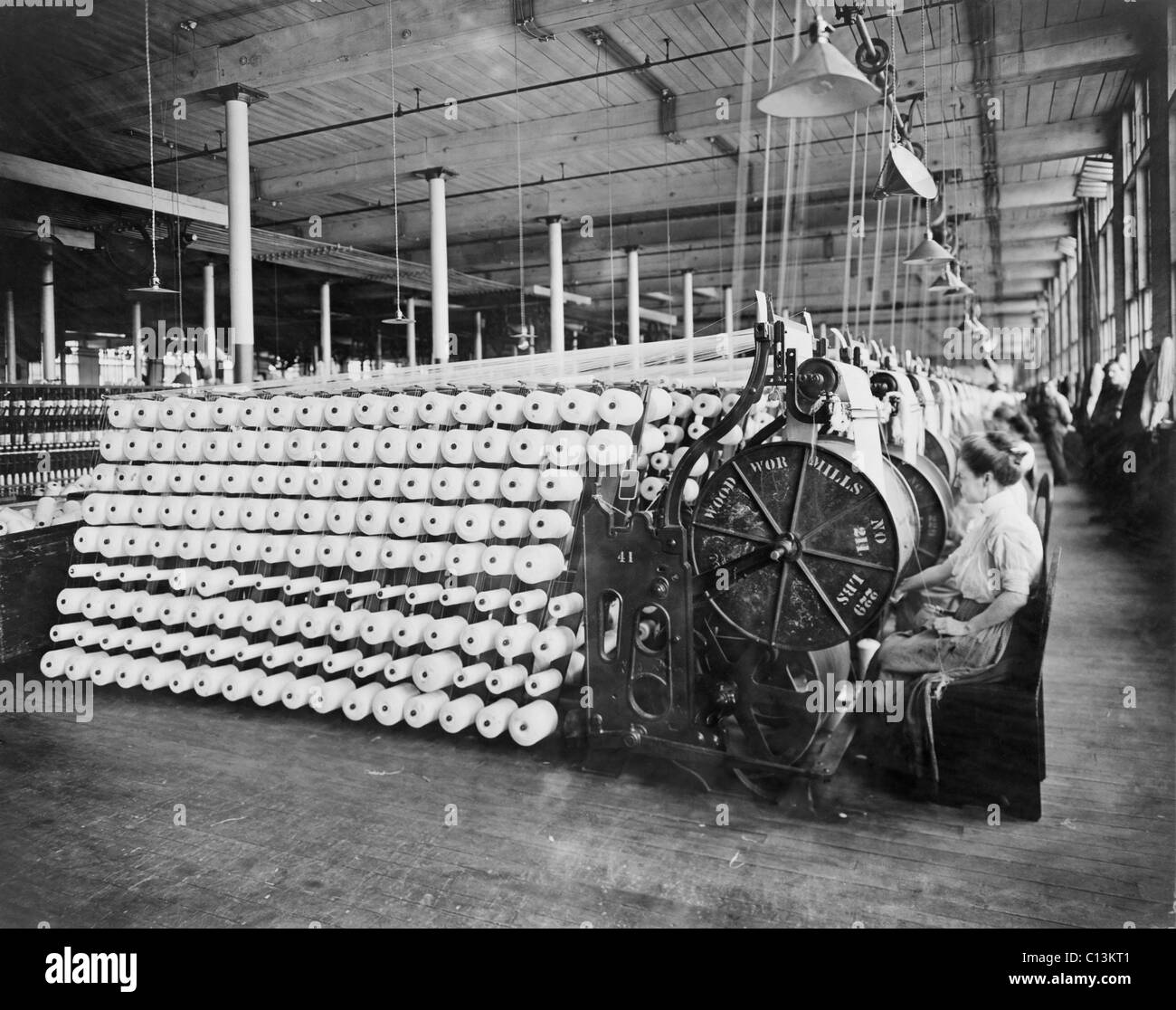

Beneath the glittering façade of industrial success lay a stark and often brutal reality for millions. Cities swelled beyond capacity, transforming into overcrowded, unsanitary tenements where families lived in squalor. Immigrants, arriving in unprecedented numbers from Southern and Eastern Europe, filled the lowest rungs of the economic ladder, working long hours for meager wages in dangerous conditions. Child labor was rampant, with children as young as five toiling in factories, mines, and fields, their childhoods sacrificed at the altar of profit.

Upton Sinclair, the muckraking journalist whose novel The Jungle (1906) exposed the horrific conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry, famously wrote: "I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach." While his intention was to highlight the plight of the workers, it was the description of rotten meat, diseased animals, and unsanitary processing that truly shocked the nation, leading directly to the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906. This was the power of the Progressive movement: to shine a light on the darkness and demand change.

The dangers were not confined to food production. Factory floors were deathtraps, with inadequate safety measures leading to countless injuries and deaths. The infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City on March 25, 1911, stands as a chilling testament to this negligence. 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women, perished because exit doors were locked to prevent theft and fire escapes were flimsy. This tragedy galvanized public opinion, leading to significant reforms in factory safety standards and workers’ compensation laws.

Beyond the workplace, political corruption was endemic. Powerful "bosses" controlled urban political machines, trading favors and votes for personal gain. Trusts and monopolies exerted undue influence on government, stifling competition and enriching their owners at the expense of consumers and small businesses. This widespread corruption eroded public trust and threatened the very foundations of American democracy.

The Clarion Call of Reform: Muckrakers and Social Workers

In response to these pervasive problems, a diverse and powerful movement for reform began to coalesce: Progressivism. It was not a single, monolithic ideology but a broad coalition of reformers – journalists, academics, social workers, politicians, and ordinary citizens – united by a belief that government could and should be an instrument for social good.

The "muckrakers" were the journalistic vanguard of this movement. Armed with pens and an unwavering commitment to truth, they delved into the darkest corners of American society, exposing corruption and injustice. Ida Tarbell’s meticulously researched The History of the Standard Oil Company (1904) systematically dismantled John D. Rockefeller’s carefully crafted public image, revealing the ruthless tactics he employed to build his oil empire. Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890), with its stark photographs and vivid descriptions, brought the squalor of New York’s tenement slums into the homes of the middle class, forcing them to confront the realities of urban poverty.

Beyond journalism, social reformers like Jane Addams established settlement houses, most famously Hull House in Chicago (1889). These institutions provided vital services to immigrant communities – English classes, childcare, healthcare, and legal aid – while also serving as centers for social research and advocacy. Addams, a pioneer in social work and a future Nobel Peace Prize laureate, articulated the Progressive belief in collective responsibility: "The good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life."

Political Progress: From the Local to the Federal

The Progressive movement’s reach extended deep into the political arena. At the local level, reformers fought for "good government" initiatives, pushing for professional city managers, non-partisan elections, and direct democracy measures like the initiative, referendum, and recall, which allowed citizens to propose and vote on laws directly.

At the state level, governors like Robert "Fighting Bob" La Follette of Wisconsin championed what became known as the "Wisconsin Idea" – using academic expertise to draft progressive legislation on issues ranging from railroad regulation to conservation.

However, it was at the federal level that the Progressive Era truly made its indelible mark, largely through the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson.

The Roosevelts and Wilson: Presidential Champions of Change

Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), an energetic and charismatic leader, embodied the Progressive spirit. He famously declared war on "malefactors of great wealth" and earned the nickname "trust-buster" for his efforts to break up monopolies like J.P. Morgan’s Northern Securities Company. Roosevelt believed in a "Square Deal" for all Americans, advocating for stricter regulation of railroads (Elkins Act, Hepburn Act), consumer protection (Pure Food and Drug Act, Meat Inspection Act), and, notably, environmental conservation. He established five national parks, 51 federal bird reserves, and 150 national forests, fundamentally changing the nation’s approach to its natural resources.

His successor, William Howard Taft (1909-1913), despite a more reserved demeanor, continued Roosevelt’s trust-busting efforts, prosecuting even more trusts than TR. He also supported the establishment of the Children’s Bureau and the passage of the 16th (income tax) and 17th (direct election of senators) Amendments, both key Progressive achievements.

Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921), a former academic and governor of New Jersey, brought his own brand of Progressivism, dubbed the "New Freedom," to the White House. He focused on strengthening government oversight of the economy. His administration created the Federal Reserve System in 1913, establishing a decentralized central bank to manage the nation’s currency and credit. He also signed the Clayton Anti-Trust Act (1914), which strengthened the Sherman Anti-Trust Act by outlawing specific anti-competitive practices, and created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to monitor business practices. Wilson also oversaw the passage of the 19th Amendment (1920), finally granting women the right to vote, a culmination of decades of tireless advocacy by suffragists.

The Enduring Legacy

By the end of World War I, the Progressive Era began to wane, giving way to the exuberance of the Roaring Twenties. Yet, its impact on American society was profound and enduring. The era fundamentally reshaped the relationship between government and industry, establishing the principle that the government had a legitimate role in regulating the economy and protecting the welfare of its citizens.

From the safety standards in our workplaces to the purity of our food and medicine, from the preservation of our national parks to the very mechanisms of our democracy, the Progressive Era left an indelible mark. It taught America that progress, while often driven by industrial might, must also be tempered by a commitment to social justice and a shared responsibility for the common good. The questions it grappled with – the balance between individual liberty and collective welfare, the role of government in a capitalist society, and the pursuit of a more perfect union – remain as relevant today as they were a century ago. The crucible of progress forged not just modern industry, but also the very conscience of modern America.