The Crucible of Statehood: West Virginia’s Civil War Odyssey

In the annals of American history, few stories encapsulate the profound divisions and transformative power of the Civil War quite like the birth of West Virginia. Forged in the crucible of conflict, born from a unique act of "secession from secession," this rugged mountain state stands as a singular testament to the war’s ability to redraw maps, redefine loyalties, and reshape identities. Its struggle was not merely a side act to the grander campaigns but a crucial, often brutal, internal conflict that fundamentally altered the political landscape of the nation.

When the cannons roared at Fort Sumter in April 1861, plunging the United States into civil war, the Commonwealth of Virginia faced an agonizing choice. Predominantly an agricultural state with a significant enslaved population, its eastern counties felt a strong affinity with the burgeoning Confederacy. Yet, the western counties, separated by the formidable Appalachian Mountains, had long harbored distinct grievances. Their economy was based more on small farms and nascent industry, their social structure boasted fewer large slaveholders, and their political interests often diverged sharply from the tidewater aristocracy that dominated Richmond. This geographical and cultural chasm would prove to be the fault line upon which a new state would be built.

As Virginia moved inexorably towards secession, western Unionists saw their chance. On April 17, 1861, the Virginia Secession Convention voted to leave the Union. But the delegates from the western counties, primarily from the region north and west of the Allegheny Mountains, overwhelmingly rejected the measure. They quickly convened their own assemblies, first in Clarksburg and then in Wheeling, to chart a separate course. These "Wheeling Conventions" were revolutionary in their intent, asserting that if the legitimate government of Virginia had betrayed the Union, then the loyal citizens had the right to form a "Restored Government" of Virginia.

Francis H. Pierpont was elected governor of this Restored Government, which immediately sought recognition from Washington D.C. This move was not without its constitutional quandaries. The U.S. Constitution stipulated that a new state could not be formed from an existing one without the consent of the original state’s legislature. Abraham Lincoln, ever the pragmatist, recognized the military and political advantages of supporting the western Virginians. Not only would it weaken the Confederacy by carving away a significant portion of its most populous state, but it would also secure vital transportation routes, most notably the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad, a critical Union supply line.

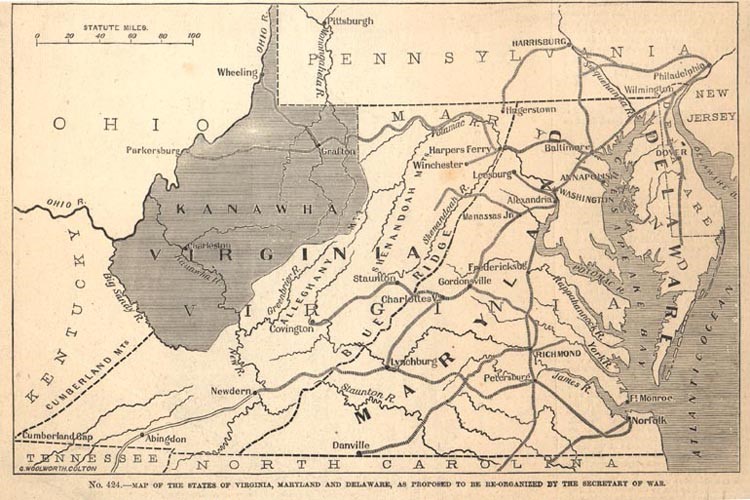

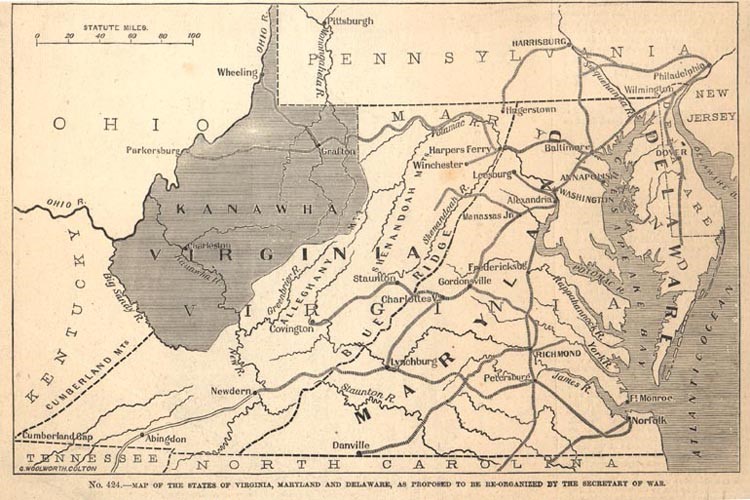

The process was arduous. A constitutional convention met in Wheeling from November 1861 to February 1862, drafting a document for the proposed state of "Kanawha," later renamed West Virginia. The issue of slavery, though less prevalent in the western counties, remained a contentious point. To gain congressional approval, a provision for gradual emancipation was eventually included in the state’s constitution, a compromise that appeased abolitionists and secured Lincoln’s signature. On June 20, 1863, West Virginia officially became the 35th state, a dramatic and unprecedented act of state creation in the midst of civil war.

While the political maneuvering played out in convention halls, the battlefields of West Virginia were anything but quiet. The region became a crucial theater in the early stages of the war. Union General George B. McClellan, then a rising star, led a successful campaign in the summer of 1861, securing the western counties for the Union. His victories at Philippi (often cited as the first land battle of the war, though more of a skirmish known as "The Philippi Races"), Rich Mountain, and Corrick’s Ford were instrumental in establishing Union control and boosting Northern morale. McClellan famously declared, "The Rebels are demoralized and the feeling of the Union men is that we have wiped out the stain of their secession." These early engagements were critical not only for their strategic value in controlling the B&O Railroad but also for demonstrating the Union’s ability to operate effectively in challenging mountain terrain.

However, the war in West Virginia was far more complex than conventional battles. It was a brutal, localized conflict marked by intense guerrilla warfare, bushwhacking, and deeply personal feuds. Families were often torn asunder, with brothers fighting on opposing sides. "Brother against brother" was not just a metaphor here; it was a daily reality. One contemporary account described the region as "a land where every man was his own law, and every quarrel settled by the rifle." Union and Confederate forces, as well as irregular partisan bands, roamed the rugged landscape, often preying on civilians, burning homes, and seizing property.

Confederate efforts to reclaim the region were persistent but ultimately unsuccessful. Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson (a native of what would become West Virginia, born in Clarksburg) both led campaigns into the mountains, but the terrain, the fierce Unionist sentiment among the populace, and logistical challenges proved insurmountable. Raids by Confederate cavalry leaders like John McCausland and William L. Jackson (Stonewall’s cousin) aimed to disrupt Union supply lines and recruit sympathizers, but they could not fundamentally shift the balance of power. The Jones-Imboden Raid in 1863, for example, saw Confederate forces sweep through the state, destroying infrastructure and capturing supplies, but failed to ignite a widespread uprising against Union control.

The civilian population endured immense suffering. Farms were plundered, livestock stolen, and communities terrorized by both sides. Women and children were left to fend for themselves as men marched off to war or disappeared into the bush. The very act of declaring loyalty could be a death sentence, leading many to feign neutrality or constantly shift their allegiances to survive. The mountains, once a barrier between eastern and western Virginia, now became a labyrinthine stage for ambushes, skirmishes, and acts of individual vengeance.

By the war’s end, West Virginia had contributed approximately 32,000 soldiers to the Union cause, a remarkable number for its relatively small population. While a smaller contingent of perhaps 6,000-9,000 men fought for the Confederacy, the state’s overwhelming commitment to the Union was undeniable. Its formation had been a strategic masterstroke for Lincoln, demonstrating the fragility of the Confederacy’s claim to unified support and providing a powerful symbol of national unity.

The legacy of the Civil War in West Virginia is multifaceted and enduring. It solidified a distinct identity, one born of resistance and self-determination. The war’s end brought the challenge of reconciliation, as communities attempted to mend the deep rifts created by years of bitter conflict. The state’s unique path to statehood profoundly shaped its political culture, fostering a strong sense of independence and often a distrust of external authority. Economically, the war’s demands for resources and the subsequent expansion of railroads laid the groundwork for the state’s later industrial boom, particularly in coal mining and timber.

Today, West Virginia proudly embraces its "born during the Civil War" narrative. Historical markers, battlefields, and museums across the state tell the story of a people who, when faced with an impossible choice, chose to forge their own destiny. The mountainous terrain that once divided them from their eastern counterparts became the very cradle of their new identity, a testament to the fact that even amidst the most destructive of conflicts, new beginnings can emerge, forever altering the fabric of a nation. The story of West Virginia is not just a footnote to the Civil War; it is a vital chapter, illustrating the profound and often surprising ways in which the war reshaped American geography, politics, and the very concept of national belonging.