The Dene Tapestry: Tracing the Vast and Resilient Athabascan Family Across North America

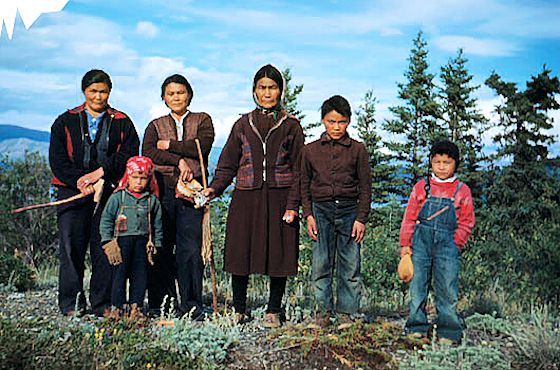

Across the frigid tundra of Alaska, down through the boreal forests of Canada, and into the sun-baked deserts of the American Southwest, an ancient and enduring story unfolds. It is the narrative of the Athabascan family, a linguistic and cultural grouping so vast, so diverse, and so deeply interwoven with the very fabric of North America that its full scope often goes unrecognized. More accurately known by many of their own peoples as the Dene (pronounced "Deh-nay"), meaning "the people," this family represents a testament to human adaptability, resilience, and the profound connection between language, land, and identity.

To speak of "Athabascan" is to encompass a staggering array of distinct nations, each with its unique history, traditions, and dialects, yet all bound by a common linguistic ancestor. This family is the second-largest Indigenous language family in North America, trailing only Algonquian in terms of the number of languages spoken. Its geographic spread is nothing short of immense, creating a cultural bridge that spans continents and climates.

A Continent-Spanning Legacy

The Athabascan homeland stretches from the interior of Alaska, through the Yukon and Northwest Territories, across British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, reaching into parts of Ontario and Quebec. But the story doesn’t end there. A dramatic and ancient migration carried a significant branch of the Athabascan family thousands of miles south, giving rise to the Apache and Navajo (Diné) peoples of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado. Further west, smaller, distinct Athabascan communities are found along the Pacific Coast in Oregon and California, including the Hupa, Tolowa, and Mattole.

This incredible distribution means that Athabascan peoples have adapted to virtually every major North American ecosystem. The Gwich’in of the Arctic interior are caribou hunters, their lives intricately tied to the migration patterns of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. The Tłı̨chǫ (Dogrib) of the Northwest Territories are known for their sophisticated knowledge of the subarctic landscape, adept at hunting moose and fishing. In contrast, the Diné (Navajo) of the Southwest developed complex agricultural practices alongside sheep herding, their hogans dotting a landscape of red rock and mesas. The Carrier people of British Columbia navigated dense forests and salmon-rich rivers, while the Apache became legendary for their horsemanship and martial prowess in arid environments.

This ecological diversity fostered a rich tapestry of distinct cultures, each with its own spiritual beliefs, governance structures, artistic expressions, and oral traditions. Yet, underlying this diversity is a shared worldview often characterized by a deep respect for the land, a strong sense of community, and an emphasis on reciprocity.

The Linguistic Heartbeat: Complexity and Connection

At the core of the Athabascan identity is its language family. Athabascan languages are renowned among linguists for their complexity, particularly their highly intricate verb structures. They are polysynthetic, meaning that many morphemes (meaningful units) can be strung together to form a single, long word, often conveying what would require an entire sentence in English. They are also tonal, meaning the pitch of a word can change its meaning, a feature more commonly associated with East Asian languages.

The precision and descriptive power of these languages are profound. For example, a single verb conjugation in a language like Koyukon (spoken in interior Alaska) can specify not just what is happening, but who is doing it, to whom, how they are doing it, what kind of object is involved, and even the shape or state of that object. This linguistic depth reflects a worldview that pays meticulous attention to detail and relationships within the environment.

Linguist Edward Sapir, a pioneer in Indigenous language studies, first proposed the broader "Na-Dene" phylum, linking Athabascan languages with Tlingit and Eyak. More controversially, some linguists have suggested a distant genetic relationship between Na-Dene and Yeniseian languages of Siberia (like Ket), which could imply a very early migration route across the Bering Strait, distinct from the ancestors of other Indigenous North Americans. While this "Dene-Yeniseian" hypothesis remains a subject of active debate, it highlights the deep historical roots and potential global connections of the Athabascan family.

Ancient Journeys: The Southward Migration

One of the most compelling narratives within the Athabascan story is the southward migration. Sometime between 1,000 and 600 years ago, a group of Athabascan-speaking peoples began a monumental journey from the subarctic, moving south through the interior of the continent. This epic trek eventually led them to the American Southwest, where they encountered and interacted with established Pueblo cultures. Over centuries, these migrating groups adapted to their new desert environment, evolving into the distinct Apache and Diné (Navajo) nations we know today.

The Diné, in particular, flourished, becoming the largest federally recognized tribe in the United States. Their language, Diné Bizaad, is the most widely spoken Indigenous language north of Mexico. This remarkable journey underscores the adaptability and resilience inherent in the Athabascan spirit, capable of transforming cultures and lifeways while retaining the core of their linguistic and ancestral heritage.

A Legacy of Challenge and Resilience

The history of Athabascan peoples, like that of many Indigenous groups, is also one marked by immense challenges following European contact. Colonial expansion brought disease, warfare, forced relocation, and the systematic erosion of traditional lifeways. The imposition of residential schools (in Canada) and boarding schools (in the U.S.) aimed to "kill the Indian in the child," forcibly separating generations from their families, languages, and cultures. This trauma continues to impact Athabascan communities today.

Resource extraction, from the gold rushes of the Yukon to the oil and gas developments in the Arctic and Alberta, has often occurred on Athabascan lands without adequate consent or benefit, leading to environmental degradation and disruption of traditional subsistence practices. Land claims and treaty negotiations remain ongoing, as communities strive to assert their sovereignty and protect their ancestral territories.

Yet, despite these profound historical and ongoing challenges, the Athabascan spirit endures. It is a story of profound resilience and revitalization. Across the vast Athabascan homeland, communities are actively engaged in powerful efforts to reclaim and strengthen their languages and cultures.

"Our language is who we are," says Elder Sarah Charlie, a fictional but representative voice from an Athabascan community, reflecting a sentiment widely held. "It carries our stories, our knowledge, our connection to the land and to our ancestors. To lose it is to lose a part of our soul." This understanding fuels language immersion schools, cultural camps, and community-led initiatives designed to pass on the knowledge of elders to younger generations. Apps, online dictionaries, and media in Athabascan languages are becoming increasingly common, leveraging modern technology for ancient wisdom.

Quotes and Enduring Contributions

The Navajo Code Talkers of World War II stand as a powerful symbol of Athabascan resilience and contribution. Their unbreakable code, based on the Diné language, was instrumental in securing victory for the Allies in the Pacific Theater. As Chester Nez, one of the original 29 Code Talkers, famously stated, "The enemy never understood it." This remarkable achievement not only highlighted the complexity and security of the Diné language but also served as a profound testament to the patriotism and ingenuity of Indigenous peoples, often at a time when their own rights were denied at home.

In the North, the Gwich’in Nation’s decades-long fight to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) from oil and gas drilling is another powerful example of enduring commitment. For the Gwich’in, the coastal plain of ANWR is the calving ground of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, their izhik gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit – "the sacred place where life begins." Their struggle is not merely environmental; it is a fight for cultural survival, a testament to the inextricable link between the land, animals, and the spiritual well-being of the people. "Our identity is tied to the caribou," explains Gwich’in activist Bernadette Demientieff. "If the caribou disappear, we disappear."

The Future: A Continuing Journey

The Athabascan family continues to navigate the complexities of the 21st century. Issues of self-determination, economic development, climate change, and the ongoing work of reconciliation remain central. Yet, the deep roots of their cultures, the strength of their languages, and the unwavering connection to their ancestral lands provide a foundation for a vibrant future.

From the quiet dignity of a Gwich’in elder sharing caribou stories in the Yukon to the vibrant arts of the Diné in New Mexico, the Athabascan family embodies a living history of North America. Their collective narrative is one of extraordinary adaptation, profound linguistic depth, and an unyielding spirit in the face of adversity. They are the Dene, "the people," a vast tapestry woven across a continent, whose threads continue to strengthen and intertwine, enriching the cultural landscape of the world. Their story is not just a chapter in the history of Indigenous peoples; it is a fundamental part of the human journey itself.