The Dragon’s Diaspora: A Global Saga of Chinese Immigration

From the rugged peaks of "Gum Shan" to the gleaming towers of global financial centers, the saga of Chinese immigration is a sprawling, multifaceted narrative that has profoundly shaped nations and redefined communities across continents. It is a story of ambition, resilience, hardship, and triumph, reflecting not just the individual journeys of millions but also the shifting geopolitical landscapes and economic currents that have propelled one of the world’s largest diasporas.

The roots of significant Chinese emigration can be traced back to the mid-19th century, a period marked by profound upheaval in China. The Opium Wars, internal rebellions like the Taiping Uprising, and devastating famines plunged vast regions into poverty and instability. Simultaneously, the promise of opportunity beckoned from afar. News of California’s mineral riches, particularly the "Gold Mountain" (Gum Shan) in North America, ignited a fervent desire for a better life among the impoverished coastal populations of Guangdong and Fujian provinces.

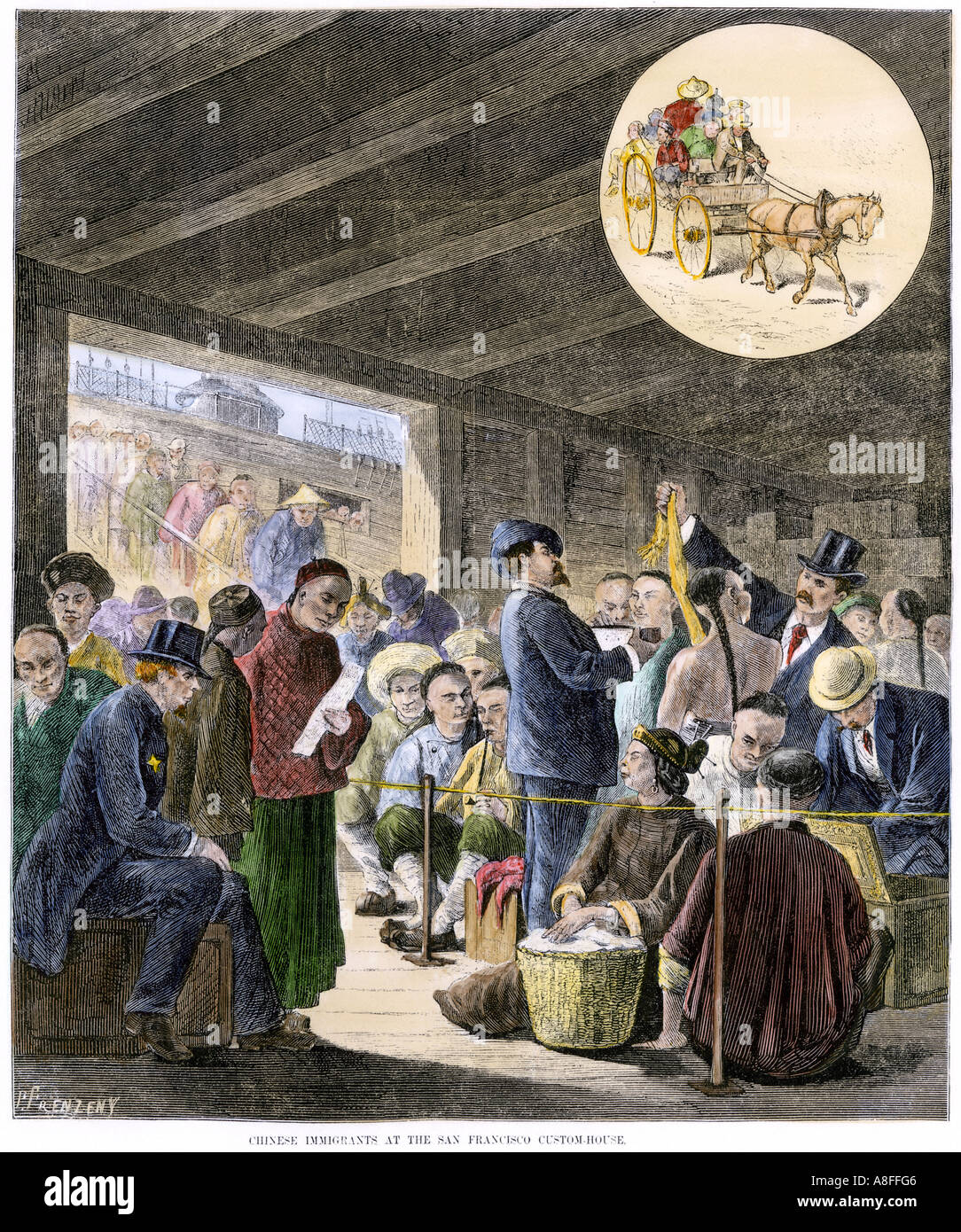

These early pioneers, often young men known as "sojourners," initially intended to return home wealthy after striking it rich. They arrived on the shores of the United States, Canada, Australia, and parts of Southeast Asia, seeking their fortunes. In America, after the initial gold rush waned, Chinese laborers became indispensable to the burgeoning industrial economy. They famously comprised over 90% of the Central Pacific Railroad’s workforce, enduring perilous conditions and back-breaking labor to lay tracks across the treacherous Sierra Nevada mountains. Their contribution was monumental, yet often met with a bitter irony of appreciation mixed with intense prejudice.

"They built the railroads, they drained the swamps, they reclaimed the land," remarked historian Erika Lee, highlighting their undeniable contributions. Yet, as economic anxieties mounted and racial prejudices intensified, the welcome mat quickly turned into a barrier. White laborers, feeling threatened by what they perceived as cheap Chinese labor, spearheaded a virulent anti-Chinese movement. This xenophobia manifested in discriminatory laws, violence, and the infamous "Queue Ordinances" that forced Chinese men to cut their traditional braids.

The culmination of this hostility was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first federal law in US history to suspend immigration of a specific ethnic group. This landmark legislation, and subsequent expansions, effectively barred Chinese laborers from entering the country for decades and severely restricted family reunification. It enshrined a legal framework of racial discrimination that would last for over 60 years.

During this period of exclusion, Chinese communities in the West became more insular, creating the first "Chinatowns" – self-sufficient enclaves offering mutual support, cultural familiarity, and protection from external hostility. Yet, even within these communities, life was challenging. Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay, often dubbed the "Ellis Island of the West," became a symbol of this era’s discrimination. Unlike European immigrants who were often processed quickly, Chinese immigrants, even those with legal claims, faced grueling interrogations, prolonged detentions, and the constant threat of deportation.

To circumvent the Exclusion Act, a clandestine system of "paper sons" and "paper daughters" emerged. Chinese immigrants would purchase fraudulent documents claiming familial ties to US citizens or legal residents, allowing them to enter. This created complex, fabricated family trees that would haunt generations during later immigration interviews, where inconsistencies could lead to harsh consequences.

The geopolitical landscape of World War II brought a subtle shift. With China as an ally against Japan, the Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1943. While symbolic, this repeal was largely a gesture of wartime solidarity and did not immediately open the floodgates, initially allowing only a minuscule quota of 105 Chinese immigrants per year.

The true watershed moment, however, arrived with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This landmark legislation abolished the discriminatory national origins quota system, fundamentally reshaping American immigration policy. By prioritizing family reunification and skilled labor, the 1965 Act inadvertently opened the door for a massive influx of Chinese immigrants, many of whom were well-educated professionals, scientists, and entrepreneurs. This marked a significant departure from the earlier waves of largely unskilled laborers.

"The 1965 Act transformed the face of American immigration," notes Mae Ngai, a prominent historian of Asian American history. "It allowed for the formation of vibrant, diverse Chinese American communities that were no longer solely confined to traditional Chinatowns."

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed new, diverse waves of Chinese immigration, driven by a complex interplay of "push" and "pull" factors. Economic liberalization in China, coupled with global opportunities, has spurred a significant outflow of highly skilled professionals, entrepreneurs, and students. Many seek advanced education in Western universities, contributing to a global "brain drain" from China, though an increasing number are also returning, contributing to a "brain gain" for their homeland.

This modern wave is characterized by its diversity. Alongside the skilled professionals, there are increasing numbers of wealthy investors seeking to diversify assets and secure better educational and environmental opportunities for their children. Students form a significant contingent, making Chinese international students the largest foreign student population in many Western countries, particularly the United States. These "new immigrants" often arrive with higher levels of education and capital, integrating into sectors like technology, academia, and finance, and creating new "ethnoburbs" – suburban concentrations of affluent Chinese immigrants.

The impact of Chinese immigrants on their host nations is immeasurable. Economically, they have been engines of growth, from the laundries and restaurants of early Chinatowns to the tech startups and research labs of today. Their entrepreneurial spirit has created countless businesses, jobs, and contributed significantly to local and national economies. Remittances sent back to China have also played a crucial role in supporting families and local economies in their ancestral villages.

Culturally, Chinese immigration has profoundly enriched the global tapestry. Chinatowns, once enclaves of necessity, have evolved into vibrant cultural centers and tourist attractions, introducing dim sum, Chinese New Year celebrations, and martial arts to a wider audience. Chinese cuisine, in particular, has become a staple across the world, adapting and evolving with local tastes while retaining its distinct flavors. The presence of Chinese communities has also spurred a greater understanding and appreciation of Chinese language, philosophy, and art.

Yet, the journey has never been without its formidable challenges. Discrimination, economic exploitation, and periodic outbreaks of anti-Asian sentiment continue to punctuate the narrative. The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, saw a resurgence of xenophobia and hate crimes against people of Asian descent, reminding the diaspora that deeply rooted prejudices can resurface even in modern societies. Navigating cultural differences, language barriers, and the complexities of identity – balancing their heritage with integration into new societies – remains an ongoing process for many.

In an era of increasing geopolitical tension, particularly between the United States and China, the Chinese diaspora sometimes finds itself navigating complex loyalties and facing renewed scrutiny. Concerns about espionage, intellectual property theft, and political influence have led to heightened surveillance and suspicion, particularly towards academics and scientists of Chinese origin. This has created a challenging environment for many who simply wish to contribute to their adopted homes while maintaining ties to their heritage.

Despite these hurdles, the resilience of the Chinese diaspora is a testament to their enduring spirit. Their ability to adapt, innovate, and build strong communities in the face of adversity speaks volumes. The question of identity – whether one is Chinese, American Chinese, Canadian Chinese, or a global citizen with Chinese heritage – remains a fluid and evolving concept, shaped by personal experience, generational shifts, and the ever-changing global landscape.

From the desperate search for "Gold Mountain" to the sophisticated networks of a globalized world, the story of Chinese immigration is a powerful testament to human ambition, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of a better life. It is a narrative that continues to be written, enriching the world with its myriad contributions and reminding us of the enduring power of human mobility and the complex, beautiful tapestry of a globalized society. The dragon’s diaspora, a force shaped by history and shaping the future, continues its journey, weaving its indelible mark across the world.