The Dust and Dreams: Forging American Legends on the Abilene Trail

America is a land woven from narratives, a tapestry rich with the exploits of pioneers, the wisdom of indigenous peoples, the grit of frontiersmen, and the daring of outlaws. These are the legends, not always strictly historical fact, but enduring tales that capture the spirit of a nation constantly reinventing itself. From the misty forests of the Appalachians to the sun-baked deserts of the Southwest, every corner of this vast continent holds its own mythos. Yet, few eras have imprinted themselves on the American psyche with the vividness and romantic allure of the Wild West, and fewer arteries of that West pulsed with more life, danger, and legend than the Abilene Trail.

The period immediately following the American Civil War was one of profound transformation. The nation, scarred but reunited, looked westward, driven by Manifest Destiny, economic opportunity, and the sheer human urge for exploration. This was the era of the cowboy, the cattle drive, the boomtown, and the gunslinger – a crucible in which the raw elements of frontier life were forged into an enduring national mythology. At the heart of this unfolding drama, for a crucial few years, lay the Abilene Trail, a lifeline that connected the vast, beef-rich plains of Texas with the hungry markets of the East, forever etching its mark on the landscape of American legend.

The Birth of a Cattle Kingdom: Joseph G. McCoy’s Vision

Before the Abilene Trail, getting Texas cattle to market was a monumental challenge. Millions of longhorns roamed the Texas plains, a valuable resource, but the journey to distant railheads was fraught with peril, often ending in meager profits for the drovers. The problem was a logistical nightmare: how to bridge the gap between supply and demand across hundreds of miles of unsettled, often hostile, territory.

Enter Joseph G. McCoy. A shrewd, visionary Illinois cattle dealer, McCoy arrived in Kansas in 1867 with a audacious plan. He saw the potential of the Kansas Pacific Railway and recognized that a strategically located railhead could unlock the wealth of Texas beef. He chose a small, sleepy whistle-stop called Abilene, a town with little more than a dozen log huts and a few hundred acres of prairie. What Abilene lacked in infrastructure, it made up for in location: it was far enough west to avoid the settled farmlands of eastern Kansas, where farmers feared – often with good reason – the spread of "Texas fever" from the longhorns.

McCoy invested heavily, building corrals, a hotel, a bank, and even a large stockyard capable of holding 3,000 cattle. He then launched an aggressive marketing campaign, sending agents into Texas to spread the word: Abilene was open for business. He promised good prices, safe passage, and reliable rail transport. His gamble paid off spectacularly. "He built a town where none had been, and a market where none had existed," wrote historian Wayne Gard. "His vision, his tireless promotion, and his shrewd understanding of the economics of the cattle industry created a revolution."

The Long Drive: An Epic Journey of Grit and Peril

The cowboys of Texas answered McCoy’s call. What followed was one of the most iconic and arduous journeys in American history: the cattle drive. From 1867 to 1872, an estimated three to five million longhorns thundered north along what became known as the Abilene Trail, a loose network of paths stretching over 800 miles from South Texas to the Kansas railhead.

The long drive was not for the faint of heart. A typical drive involved 2,500 to 3,000 cattle and a crew of about a dozen cowboys, led by a trail boss. Their days began before dawn and ended long after sunset, punctuated by the rhythmic creak of the chuck wagon, the lowing of the cattle, and the constant vigilance against danger. The work was monotonous and exhausting, but punctuated by moments of extreme peril.

Stampedes were the cowboy’s greatest fear, often triggered by a sudden noise, a lightning strike, or even a frightened jackrabbit. "A thousand longhorns, running wild in the dark, could flatten a man and horse in seconds," recounted one old drover. River crossings were equally treacherous, with strong currents, quicksand, and the risk of cattle drowning or scattering. Rustlers, often former soldiers or desperate men, preyed on the herds, while conflicts with Native American tribes, whose lands were being encroached upon, were also a constant threat, though less common along the Abilene Trail’s main routes than other trails. Weather was an unforgiving master: scorching sun, torrential rains, hailstorms, and sudden blizzards could turn a drive into a fight for survival.

The cowboy himself became a legend. Often young, hardy, and skilled horsemen, they were a diverse lot, including a significant number of Black and Mexican cowboys – a fact often overlooked in popular mythology. They developed a unique culture, a code of conduct, and a set of skills perfectly adapted to the open range. Their attire – the wide-brimmed hat, bandana, chaps, and boots – became an iconic symbol of the American West. They were, as one historian put it, "the last true American nomads, living a life of absolute freedom and constant danger."

Abilene: The Wild Heart of the Cattle Kingdom

Upon reaching Abilene, the dusty, weary cowboys and their charges entered a different kind of wildness. The town, transformed from a sleepy village into a booming cattle entrepôt, became a microcosm of the frontier’s raw energy. Saloons, gambling halls, and dance houses sprang up overnight to cater to the needs and desires of thousands of cowboys, who, after months of hardship on the trail, were eager to spend their wages.

This influx of men, money, and liquor inevitably led to violence. Abilene earned a reputation as one of the wildest towns in the West. To bring order to the chaos, town fathers often hired legendary lawmen. The most famous was James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok, who served as Abilene’s marshal in 1871. Hickok, a figure already shrouded in myth from his exploits as a scout and gunfighter, was known for his unerring aim and his willingness to use it. His tenure in Abilene was marked by famous confrontations, including the shooting of gambler Phil Coe, further cementing his status as an archetypal frontier hero. "Wild Bill was a figure of fear and respect," wrote one contemporary. "His very presence was often enough to quell a disturbance, but when it wasn’t, his six-shooters spoke with finality."

The cattle towns like Abilene, Dodge City, and Ellsworth became the dramatic stages where the legends of the Wild West were truly born. Here, the lines between lawman and outlaw blurred, where quick draws decided fates, and where reputations were forged in the crucible of lead and liquor.

The End of an Era, The Birth of Enduring Myth

By 1872, the Abilene Trail’s dominance began to wane. Settlers pushed further west, their fences and farms encroaching on the open range. Other railheads emerged in Kansas, like Dodge City, and the Chisholm Trail eventually surpassed the Abilene Trail in volume. But the brief, explosive era of Abilene as the cattle capital had already etched itself into the American consciousness.

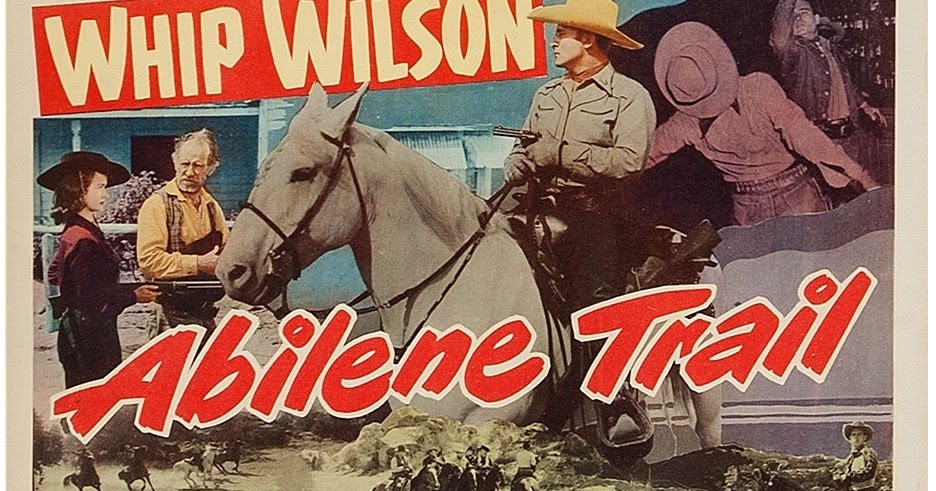

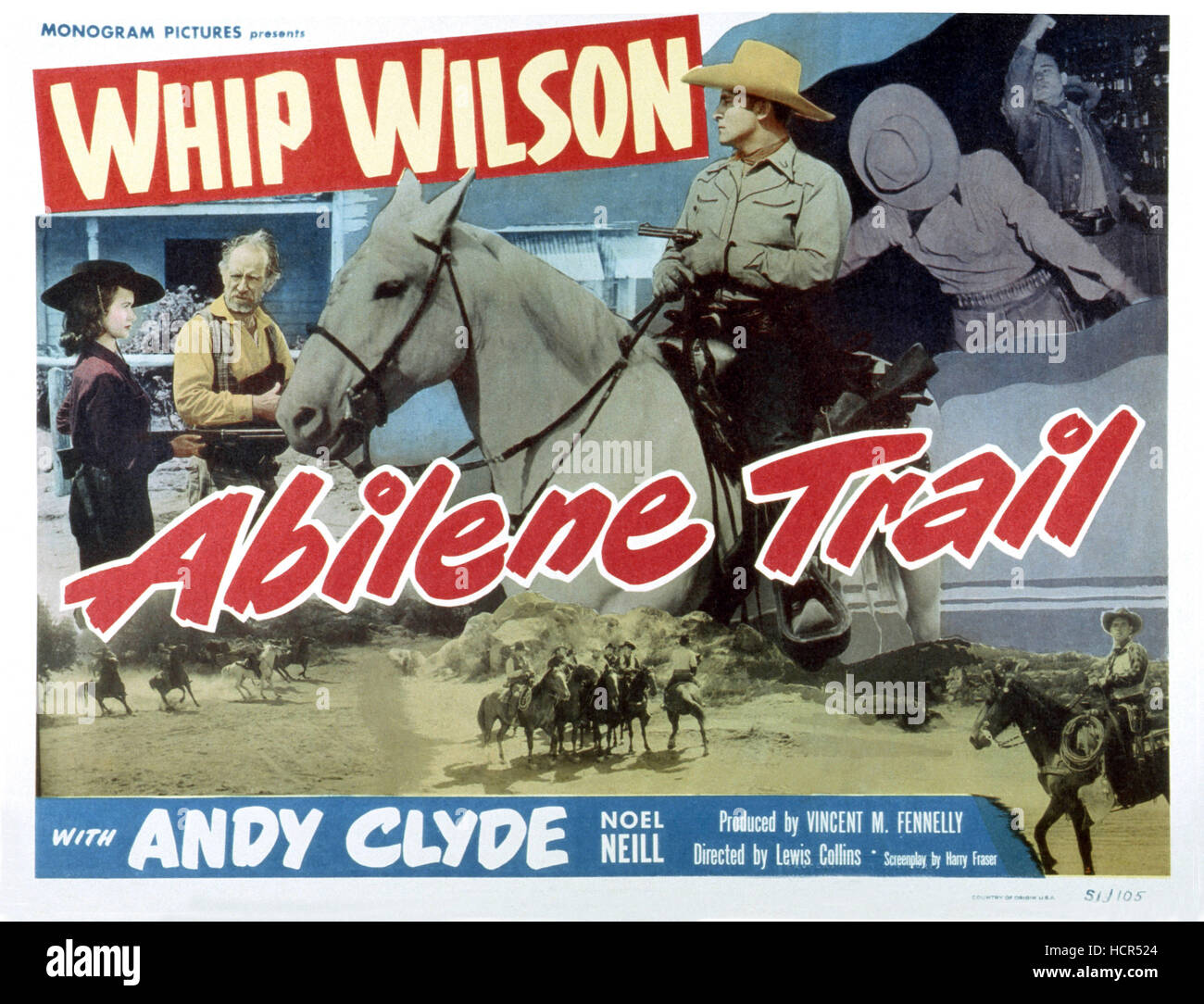

The legends born on the Abilene Trail – of the stoic cowboy, the daring drover, the ruthless outlaw, and the steadfast lawman – did not fade with the closing of the trail. Instead, they were amplified and romanticized. Dime novels, Wild West shows like Buffalo Bill Cody’s, and later, Hollywood films, took these raw stories and polished them into the enduring myths we know today. These narratives, though often exaggerated, served a vital purpose: they helped define American ideals of rugged individualism, courage, perseverance, and freedom.

The cowboy, in particular, became a global icon, representing a uniquely American spirit. He was the embodiment of self-reliance, a man against the elements, shaping his destiny on the vast, untamed frontier. This image, though frequently simplified and whitewashed, continues to resonate, speaking to a primal desire for open spaces and a life lived on one’s own terms.

Beyond the Dust: The Legacy of Legends

The legends of the Abilene Trail are but one chapter in America’s vast anthology of myths. From the native creation stories that speak of sacred lands and animal spirits, to the revolutionary tales of liberty and sacrifice, to the folk heroes like Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed who tamed the wilderness with superhuman might, America has always found its identity in its stories.

Yet, the Wild West, and the Abilene Trail as its vibrant artery, holds a special place. It represents a brief, intense period of transition, a crucible where a new American identity was forged in the heat of challenge and opportunity. The dust of the long drive, the shouts of the drovers, the crack of gunfire in a boomtown saloon – these echoes resonate still, reminding us of a time when the continent was vast, the future uncertain, and the legends were as boundless as the prairie sky. They are more than just tales; they are the dreams, the struggles, and the enduring spirit of America, writ large in the annals of time.