The Dust-Laden Echoes: Tracing the Legacy of the Jones-Plummer Trail

In the annals of the American West, where legends are etched in sun-baked earth and the wind whispers tales of bygone eras, few narratives are as evocative and economically vital as that of the great cattle trails. Among them, connecting the sprawling ranches of West Texas to the burgeoning railheads of Dodge City, Kansas, lies a less celebrated, yet profoundly significant artery: the Jones-Plummer Trail. This isn’t just a line on an old map; it’s a testament to human grit, a conduit of commerce, and a ghost road that shaped the destiny of countless cattle and cowboys, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape and the very spirit of the High Plains.

The story of the Jones-Plummer Trail is inextricably linked to the post-Civil War cattle boom, a period of explosive growth fueled by an insatiable demand for beef in the rapidly industrializing East. Texas, with its vast herds of longhorn cattle, found itself in an economic paradox: an abundance of a valuable commodity, but no efficient way to get it to market. The solution lay in the arduous, often perilous, journey northward. While the Chisholm Trail captured much of the popular imagination, connecting South Texas to Kansas, the Jones-Plummer emerged as a crucial alternative for the burgeoning ranches of the Texas Panhandle and points west, particularly after the mid-1870s.

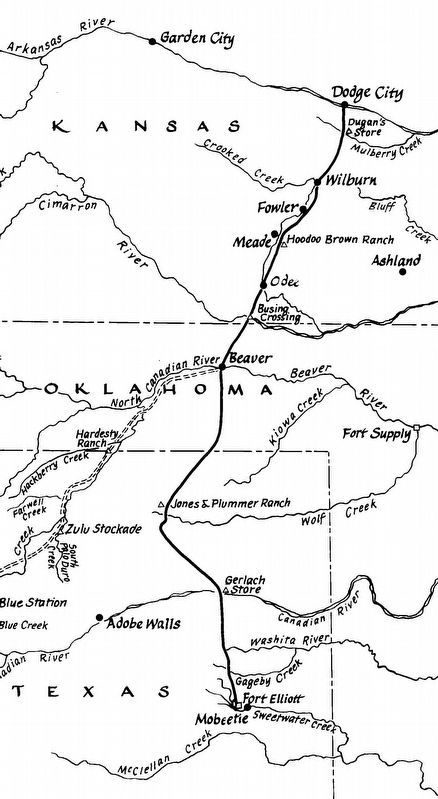

Its genesis lies in the practical needs of specific ranchers. The trail primarily served outfits like the legendary XIT Ranch, the LS Ranch, and other large operations in the Tascosa area—then a wild and woolly cowboy town on the Canadian River, often dubbed the "Cowboy Capital of the Panhandle." These ranches needed a direct, reliable route to the markets of Dodge City, Kansas, which by the late 1870s had cemented its reputation as the "Queen of the Cowtowns," a bustling hub where cattle met the railroad.

The trail takes its name from two pivotal figures: William B. "Bat" Jones and Joseph "Joe" Plummer. Bat Jones was a seasoned frontiersman, a rancher, and a trail boss who had a deep understanding of the vast, untamed territories. Plummer, equally adept, was a scout and guide, renowned for his knowledge of the High Plains, its water sources, and its challenges. Together, their expertise helped forge and refine the path that would become indispensable. They weren’t just charting a course; they were laying down the very lifeline of an industry.

"The Jones-Plummer wasn’t as famous as the Chisholm, but for the ranches of the western Panhandle, it was everything," explains historian Dr. Eleanor Vance, specializing in Western economic history. "It was their direct line to prosperity, their annual gamble against nature and human folly. Without it, the scale of ranching operations in that region would have been drastically different."

The journey itself was a monumental undertaking, stretching approximately 250 to 300 miles from Tascosa north to Dodge City. A typical drive involved herds ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 head of cattle, accompanied by a crew of 10 to 15 cowboys, a trail boss, a cook, and a wrangling crew for the remuda (the extra horses). The pace was painstakingly slow, usually 10 to 15 miles a day, allowing the cattle to graze and gain weight along the way. "You didn’t push ’em too hard," an old cowboy adage went, "or they’d lose more than they gained."

Leaving Tascosa, the trail struck north, generally following the breaks of the Canadian River, then crossing the wide, often dry, plains of the Texas Panhandle and the Oklahoma Territory (then unassigned lands). Key crossings included the Cimarron River, a notoriously temperamental waterway that could be a trickle one day and a raging torrent the next, and finally, the Arkansas River, just south of Dodge City. Each river crossing was a high-stakes operation, fraught with the risk of stampedes, drownings, and lost cattle.

Life on the trail was an unending cycle of monotony, discomfort, and sudden, heart-stopping danger. Days were long, often beginning before dawn and ending well after sunset. Cowboys, astride their sturdy horses, spent hours in the saddle, pushing the herd forward, flanking the edges, or riding the "drag" – the dusty, smelly rear of the herd where the weakest animals and the thickest dust resided. The chuck wagon, driven by the indispensable cook, was the mobile heart of the operation, providing meager but vital meals of beans, biscuits, and coffee. Nights were spent under the vast, star-dusted sky, with cowboys taking turns on guard duty, their voices often raised in mournful songs to soothe the restless cattle.

The challenges were manifold. The weather was a constant adversary: scorching summer heat that could lead to dehydration and mirages; sudden, violent thunderstorms that brought lightning, hail, and the terrifying prospect of a stampede; and unexpected blizzards in the shoulder seasons that could decimate a herd. Water, or the lack thereof, was a perennial concern, dictating the trail’s exact path and the daily rhythm. "You lived for the next water hole," one historical account from a trail boss recalls, "and prayed it wasn’t dry."

Beyond nature’s wrath, there were human threats. While the era of widespread Native American resistance was waning by the time the Jones-Plummer Trail reached its peak usage, isolated encounters and the ever-present danger of rustlers kept cowboys vigilant. A stampede, however, remained perhaps the most feared event. Triggered by a sudden noise, a lightning strike, or even a frightened rabbit, a herd of thousands of panicked longhorns could thunder across the plains, flattening anything in their path, including horses and riders. Cowboys, in acts of incredible bravery, would risk their lives to "turn the lead" of a stampede, slowly circling the runaway cattle until the herd tired and calmed.

"The Jones-Plummer Trail, like all the great cattle trails, wasn’t just about moving cows; it was about forging a distinct American identity," says Vance. "The cowboy, with his skills, his stoicism, and his unique code, was born on these trails. It was a crucible of character."

The peak years of the Jones-Plummer Trail were relatively brief, primarily spanning from the mid-1870s to the mid-1880s. Its decline, like that of the other great trails, was a consequence of progress. The relentless westward expansion of railroads into Texas and the proliferation of barbed wire fences, segmenting the open range, made long-distance cattle drives increasingly impractical and eventually obsolete. By the late 1880s, the era of the great drives was largely over, and the dust-laden paths began to fade, slowly reclaimed by the prairie grasses.

Yet, the legacy of the Jones-Plummer Trail endures. It’s etched in the landscape in subtle ways—faint ruts still visible in some remote areas, markers placed by historical societies, and the names of towns and ranches along its approximate route. More profoundly, its legacy lives on in the cultural fabric of the American West. It’s a story of audacious enterprise, of the raw courage of cowboys, and of the immense economic forces that shaped a young nation.

Today, those who venture into the vast, open spaces of the Texas Panhandle and Western Oklahoma can still feel the echoes of that time. Standing on a windswept bluff, gazing across the seemingly endless plains, it’s not hard to imagine the rumble of thousands of hooves, the lowing of cattle, the shouts of cowboys, and the creak of a chuck wagon. The Jones-Plummer Trail, though less famous than its counterparts, was no less vital. It was a testament to the pioneering spirit, a gritty artery of commerce, and a powerful reminder that even the most fleeting chapters of history can leave an eternal mark on the land and the soul. The dust may have settled, but the legend of the Jones-Plummer Trail continues to ride, an enduring symbol of the untamed American West.