The Earl Who Tried to Own Paradise: Dunraven’s Unfinished Dream in Estes Park

Estes Park, Colorado, today stands as a vibrant gateway to Rocky Mountain National Park, a bustling hub of tourism where visitors from across the globe flock to witness the majestic grandeur of the Rocky Mountains. Its main street teems with shops, restaurants, and the cheerful chatter of vacationers, all framed by the towering peaks that have captivated imaginations for centuries. Yet, beneath the veneer of modern-day commercialism lies a fascinating, often turbulent history, one significantly shaped by the audacious vision of an Anglo-Irish aristocrat who, for a fleeting period, sought to transform this wild American Eden into his private hunting preserve and an exclusive resort for the global elite: Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin, the 4th Earl of Dunraven.

Dunraven’s story in Estes Park is a compelling narrative of ambition clashing with the untamed frontier spirit, a tale of aristocratic dreams meeting the rugged individualism of the American West. It is a testament to the enduring allure of the Rockies and the complex forces that forged the identity of one of Colorado’s most iconic destinations.

An Aristocrat’s Allure to the Wild West

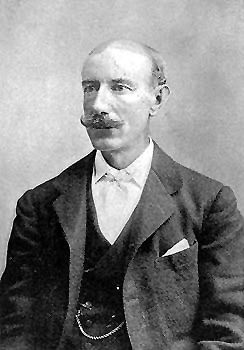

Born in 1841 into immense wealth and privilege, Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin was a quintessential figure of Victorian aristocracy. Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he inherited the Earldom of Dunraven and Mount-Earl in 1871, along with vast estates in Ireland. But the Earl was no mere drawing-room dandy; he possessed an insatiable thirst for adventure, a passion for hunting, and a keen, if sometimes romanticized, interest in the wild corners of the world. He was a seasoned traveler, a skilled yachtsman who twice challenged for the America’s Cup, a prominent politician in the House of Lords, and a prolific writer whose "Reminiscences" offer invaluable insights into his varied life.

It was this adventurous spirit that drew him to the American West in the early 1870s. The tales of boundless plains, majestic mountains, and unparalleled hunting opportunities for elk, bear, and bighorn sheep captivated the European imagination. Dunraven, accompanied by his friend and physician, Dr. George Kingsley, arrived in Colorado in 1872, seeking a cure for Kingsley’s ailing health and, perhaps more importantly, an escape into a hunter’s paradise.

Their journey led them deep into the heart of the Rocky Mountains, guided by the legendary frontiersman and scout, "Texas" Jack Omohundro. What Dunraven discovered upon entering the verdant, mountain-ringed valley known as Estes Park left an indelible mark on his soul. "It was like nothing I had ever seen," he would later write in his "Reminiscences," "a veritable paradise for the hunter, a glorious hunting ground." The valley, cradled by the snow-capped peaks of Longs Peak and Mount Meeker, with its crystal-clear streams and abundant wildlife, was, in his eyes, an unspoiled Eden.

The Grand Vision: An Exclusive Hunting Preserve

From the moment he laid eyes on Estes Park, Dunraven’s fertile imagination began to conjure a grand scheme. He envisioned not just a personal hunting retreat, but an exclusive, private game preserve and luxury resort that would cater to the world’s wealthy elite – a place where European nobility and American magnates could indulge in the thrill of the hunt amidst breathtaking scenery, far from the madding crowds of industrializing cities.

This vision was both ambitious and, as time would prove, culturally tone-deaf to the burgeoning spirit of American individualism and the frontier ethos. In England, the concept of vast, privately owned estates and exclusive hunting rights was deeply ingrained. In the American West, however, the land was largely perceived as open, free for the taking, and ripe for settlement by anyone with the grit to claim it.

Undeterred, Dunraven set about acquiring land with characteristic aristocratic determination. He established the Estes Park Company in 1874, an ambitious venture backed by significant capital. He employed agents, most notably a clever but controversial Englishman named William Hallett, to purchase vast tracts of land. These acquisitions were often made through pre-emption and homestead claims, sometimes involving questionable tactics where settlers were allegedly paid to "squat" on desirable parcels, only to transfer the deeds to Dunraven’s company. At its peak, the Earl’s holdings were said to encompass as much as 15,000 acres, effectively controlling much of the valley.

To realize his resort dream, Dunraven invested heavily in infrastructure. He built the elegant Imperial Hotel, a substantial log and stone structure that stood as a symbol of his ambition. It featured comfortable accommodations, fine dining, and boasted a well-stocked bar. He also acquired and expanded the modest Longs Peak Inn, initially built by the pioneering homesteader and guide, Enos Mills’s mentor, Griff Evans. These establishments were intended to serve as the nucleus of his exclusive empire, offering a taste of European luxury in the heart of the Rockies.

Clash of Cultures: The Frontier Fights Back

Despite Dunraven’s considerable resources and aristocratic charm, his grand vision soon encountered formidable obstacles. The first and most significant challenge was the deeply ingrained American concept of open access and the rugged individualism of the frontier. The idea that a wealthy foreign earl could simply buy up an entire valley and declare it off-limits to ordinary citizens was anathema to the settlers and prospectors who had begun to trickle into the area.

Local ranchers, trappers, and homesteaders viewed Dunraven’s land claims with suspicion and resentment. They resented the fences he erected, the restrictions he attempted to impose on hunting, and the general air of exclusivity that surrounded his operations. The "open range" was a deeply held principle, and the notion of an aristocratic "king" trying to control access to prime hunting and grazing lands was met with fierce resistance.

One prominent voice against Dunraven’s ambitions was Isabella Bird, another intrepid British traveler and writer, whose seminal work, A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains (published in 1879), offered a vivid portrayal of Estes Park in the 1870s. Bird, who stayed at Griff Evans’s cabin (later Longs Peak Inn), observed Dunraven’s activities with a critical eye. While acknowledging the Earl’s good intentions and the beauty of his planned preserve, she also highlighted the growing tension. She noted, "His aim is to keep the scenery unspoiled, and the game for legitimate sport, but the settlers, with their cattle and their unscrupulous ways, are driving both him and the game out."

Dunraven himself, in his "Reminiscences," expressed his frustration with the "squatters" and the "unruly element" of the American frontier. He wrote of the challenges of enforcing his private property rights in a land where such concepts were still fluid and often disregarded. "It was impossible to keep out the American," he lamented, "who, with his rifle and his dogs, considered himself entitled to hunt wherever he pleased." He found the American character, while admirable in its independence, to be an insurmountable obstacle to his vision of an orderly, private preserve.

Beyond the cultural clash, practical difficulties mounted. Estes Park was remote, accessible only by a long, arduous stagecoach journey. Building and maintaining luxury hotels in such a wilderness was a logistical nightmare and a significant financial drain. The harsh Colorado winters made year-round operations challenging, and the sheer scale of the land he sought to manage proved overwhelming.

The Unfulfilled Dream and a Shifting Focus

By the late 1870s and early 1880s, Dunraven’s enthusiasm for his Estes Park venture began to wane. The constant legal battles, the financial hemorrhaging, and the sheer difficulty of imposing an aristocratic European model onto the American frontier took their toll. His personal interests also shifted; his political career in the House of Lords demanded more of his time, and his passion for yachting led him to focus on his America’s Cup challenges.

Ultimately, Dunraven recognized the futility of his original plan. In 1884, he began to divest his holdings, selling off the Imperial Hotel and much of his land to various American interests, including the influential Colorado cattle baron, F.O. Stanley, who would later build the iconic Stanley Hotel. The dream of an exclusive, private hunting preserve was abandoned, a victim of the frontier spirit and the immutable forces of the American West.

Dunraven’s Enduring Legacy

While Dunraven failed to realize his grand vision of a private hunting paradise, his impact on Estes Park was undeniably profound and, in a twist of irony, ultimately beneficial for the public.

Firstly, his significant investment and development efforts put Estes Park on the map. He attracted early attention to the area, drawing the notice of other wealthy individuals and pioneering conservationists. His hotels, even if short-lived under his ownership, provided early infrastructure for tourism.

Secondly, much of the land he acquired, particularly the vast tracts surrounding Longs Peak and the high country, eventually found its way into public hands. When Rocky Mountain National Park was established in 1915, a significant portion of the land Dunraven once owned became part of this national treasure, preserving it for the enjoyment of millions rather than the exclusive pleasure of a few. The irony is stark: the man who tried to privatize paradise inadvertently helped lay the groundwork for its ultimate public preservation.

Today, Dunraven’s name echoes through Estes Park, a subtle reminder of his ambitious presence. Dunraven Street, a prominent thoroughfare, bears his moniker. Dunraven Mountain, a peak within the national park, stands as a testament to his connection with the landscape. These names serve as silent memorials to a fascinating chapter in the park’s history, a period when an earl from Ireland sought to carve out an aristocratic domain in the rugged heart of the American West.

The story of Earl Dunraven in Estes Park is more than just a historical footnote; it is a powerful allegory. It speaks to the clash of cultures, the indomitable spirit of the frontier, and the enduring allure of wild places. Dunraven, for all his aristocratic privilege, was ultimately a man captivated by the raw beauty of the Rockies. His dream, though unfulfilled in its original form, inadvertently paved the way for Estes Park to become the beloved public destination it is today, a paradise not for the chosen few, but for all who seek solace and adventure amidst its magnificent peaks. His legacy is not one of ownership, but of an unexpected, enduring contribution to the preservation and appreciation of a truly spectacular corner of the world.