The Elusive Shadow: Unearthing the ‘McCarty Gang’ and the Genesis of Billy the Kid

In the rugged annals of the American Old West, where legends were forged in the crucible of gunfire and grit, certain names echo with an undeniable resonance. Wyatt Earp, Jesse James, Doc Holliday – their stories are etched into the very fabric of American mythology. Yet, the name "McCarty Gang" might not echo with the same immediate recognition, a ghost in the vast historical landscape. This is because, in the strictest sense, no formally recognized outlaw syndicate bearing that precise moniker ever carved out a notorious existence.

Instead, to speak of the "McCarty Gang" is to delve into the very genesis of one of the West’s most infamous figures: Henry McCarty, the boy who would become William H. Bonney, better known to history as Billy the Kid. It is to explore the formative years, the shifting allegiances, and the early, often transient, associations that shaped a raw youth into a hardened outlaw, a journey from anonymity to legend. The "McCarty Gang," therefore, is less a formal criminal enterprise and more a conceptual lens through which to understand the origins of the Kid’s legend – the loose collection of friends, fellow travelers, and ultimately, fellow combatants who stood alongside him in his earliest, most defining conflicts.

From New York to New Mexico: The Boy Named Henry

Born Henry McCarty around 1859 or 1860 in the tenements of New York City, the future outlaw’s beginnings were far from the dusty plains of his eventual notoriety. His early life was marked by transience and hardship. Following the death of his Irish immigrant father, his mother, Catherine McCarty, sought a fresh start, moving west with Henry and his younger brother, Joseph. Their journey took them through Indiana, Kansas, and eventually, the burgeoning frontier towns of New Mexico Territory.

It was in Wichita, Kansas, that Catherine met and married William Antrim, a quiet, unassuming man who briefly provided a semblance of stability. Henry, for a time, was known as Henry Antrim, shedding the McCarty name, perhaps in an attempt to distance himself from a past he barely knew. But this stability was fleeting. Catherine, the anchor of their small family, succumbed to tuberculosis in Silver City, New Mexico, in 1874. Henry was barely 14.

His mother’s death was the pivotal moment, a fracture that sent Henry spiraling into a life untethered. Without a guardian, and with his stepfather largely absent, Henry was left to fend for himself in the rough-and-tumble world of a frontier mining town. He took odd jobs, drifted into petty theft, and quickly learned the harsh realities of survival. This period saw his first brushes with the law. In 1875, at the age of 15, he was arrested for stealing butter. Soon after, he was involved in stealing clothes from a Chinese laundry, an act that landed him in jail. He escaped, a feat that, while minor, foreshadowed his later, more dramatic breakouts.

This escape marked Henry McCarty’s definitive break with any semblance of a conventional life. He fled New Mexico for Arizona Territory, working as a ranch hand, a cook, and occasionally, a small-time rustler. It was here that he began to acquire a reputation, and the moniker "Kid Antrim" or simply "The Kid" started to stick. He was young, slight of build, but possessed a surprising fearlessness and a quick temper.

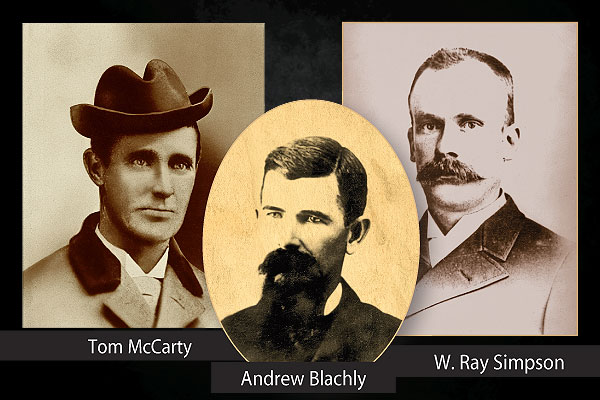

The Formation of the "Gang": Early Affiliations and the Lincoln County War

The true emergence of anything that could be construed as a "McCarty Gang" began upon Henry’s return to New Mexico in 1877. He gravitated towards the Pecos Valley, a lawless region ripe for cattle rustling and petty crime. He fell in with various groups of cowboys and drifters, men like Jesse Evans, Frank Baker, and Tom O’Keefe, who engaged in horse theft and cattle rustling. These were not highly organized criminal enterprises, but rather shifting alliances of convenience, a loose network of outlaws operating on the fringes of society. It was during this period that Henry Antrim killed his first man, Frank "Windy" Cahill, in an Arizona saloon after an argument. The killing cemented his reputation as a dangerous young man, capable of lethal violence.

However, the most significant "gang" affiliation for Billy the Kid, and the one that truly defined his legend, was not a criminal enterprise in the traditional sense, but a paramilitary faction born of conflict: The Regulators of the Lincoln County War. This brutal conflict, fought between 1878 and 1879, pitted two powerful economic and political factions against each other in a struggle for control over Lincoln County.

On one side was "The House," a powerful mercantile and ranching empire controlled by Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan, who held sway over local politics, law enforcement, and commerce. On the other side was John Tunstall, a young English rancher and businessman, who, along with his partner Alexander McSween, sought to challenge The House’s monopoly. Tunstall employed a number of young cowboys, among them Henry McCarty, who quickly became one of his most trusted hands. Tunstall, a fair and educated man, treated his employees well, and McCarty developed a genuine affection for him.

The Spark of War: Tunstall’s Murder and the Regulators’ Oath

The spark that ignited the Lincoln County War was the assassination of John Tunstall on February 18, 1878. Tunstall was ambushed and murdered by a posse led by deputies loyal to The House. His death was a betrayal of justice and a profound shock to McCarty and his fellow cowboys. "I liked Tunstall," Billy the Kid is famously quoted as saying, "and he was the only man that ever treated me like a human being."

Incensed by the murder and the apparent inability or unwillingness of the law to bring Tunstall’s killers to justice, McCarty and a group of his fellow cowboys formed "The Regulators." This was the true "McCarty Gang" in spirit, if not in name – a group bound by loyalty, a thirst for vengeance, and a commitment to what they perceived as justice. The core of this group included men like Dick Brewer, Frank Coe, George Coe, Doc Scurlock, and Charlie Bowdre – individuals who would become integral to the Kid’s story.

Their oath was clear: to avenge Tunstall’s death and bring his killers to justice, even if it meant taking the law into their own hands. The Regulators were deputized, albeit controversially, by Justice of the Peace John Wilson, who was aligned with McSween. This gave them a veneer of legality, but their actions quickly descended into vigilantism.

The Lincoln County War: Billy’s Ascent

The war escalated rapidly. On March 9, 1878, the Regulators captured and executed two of Tunstall’s killers. Then, on April 1, 1878, in a brazen act that cemented Billy’s reputation for ruthlessness and daring, the Regulators ambushed and killed Sheriff William Brady and his deputy, George Hindman, on the streets of Lincoln. Brady had been complicit in Tunstall’s murder and was a staunch ally of The House. Billy the Kid was a central figure in this ambush, reportedly taking Brady’s rifle after the shooting.

The next few months were a blur of skirmishes, ambushes, and escalating violence. The Regulators pursued members of The House faction relentlessly. Billy the Kid, despite his youth, emerged as a natural leader, admired for his courage under fire, his cool demeanor, and his deadly accuracy with a pistol. He was reportedly ambidextrous, quick to draw, and rarely missed. His youthful appearance, often described as charming and polite, belied a chilling capacity for violence.

The conflict culminated in the infamous "Five-Day Battle" in Lincoln in July 1878. The Regulators, led by McSween and Billy the Kid, found themselves besieged in McSween’s house by a large force of The House loyalists, including the newly appointed Sheriff George Peppin and a detachment of U.S. Army soldiers. The battle was a bloody siege, with both sides suffering casualties. McSween’s house was eventually set ablaze, forcing the Regulators to make a desperate dash for freedom. McSween himself was killed, along with several other Regulators. Billy the Kid, however, managed to escape the burning building, blazing his way through enemy lines.

After the War: The Outlaw Life

The Lincoln County War officially ended with the intervention of federal troops and a new governor, Lew Wallace, who offered amnesty to those involved. Billy the Kid, however, was explicitly excluded from this pardon due to his involvement in Sheriff Brady’s murder. This exclusion sealed his fate. With his perceived protectors dead or disgraced, and no path to legal absolution, Billy embraced the life of an outlaw.

He continued to ride with a shifting group of associates, engaging in cattle rustling, horse theft, and occasional skirmishes. These were his post-Regulator "gangs" – smaller, more fluid groups of criminals rather than avengers. Men like Tom O’Folliard, Charlie Bowdre (who remained fiercely loyal), and Dave Rudabaugh rode with him. They were a tight-knit unit, bound by shared danger and a distrust of authority. Their exploits became the stuff of local legend, with tales of daring raids and narrow escapes spreading across the territory.

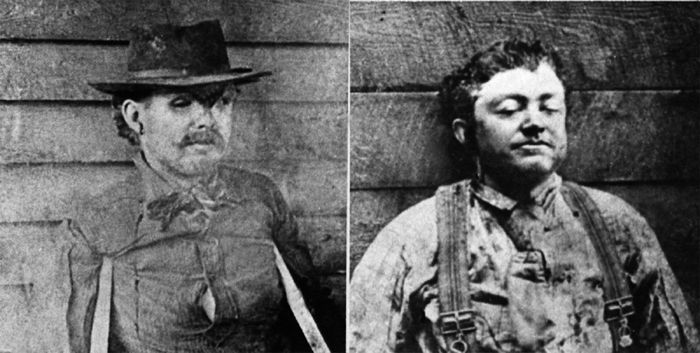

It was during this period that Pat Garrett, a former buffalo hunter and saloon owner who had once known Billy, was elected Sheriff of Lincoln County, specifically tasked with bringing in the Kid. Garrett, a formidable figure in his own right, pursued Billy relentlessly. The chase became legendary, culminating in Billy’s capture in December 1880, after a shootout at Stinking Springs that killed several of his companions, including Tom O’Folliard and Charlie Bowdre.

Billy was tried and convicted for the murder of Sheriff Brady and sentenced to hang. But true to his nature, he executed his most famous escape in April 1881, killing two deputies, James Bell and Robert Olinger, at the Lincoln County courthouse. This audacious escape cemented his reputation as an almost mythical figure, a daring individual who defied the odds.

The End of the Trail and the Enduring Legend

Pat Garrett, humiliated by the escape, renewed his hunt. The pursuit ended in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, on July 14, 1881. Garrett, acting on a tip, ambushed Billy in the darkened bedroom of Pete Maxwell. Billy, asking "Quién es?" (Who is it?), was shot twice by Garrett and died instantly. He was barely 21 years old.

The "McCarty Gang," as a literal entity, faded with the death of Henry McCarty. But the legacy of his early associations, particularly the Regulators, and his later small bands of loyalists, laid the groundwork for the enduring legend of Billy the Kid. He became a symbol of the untamed West, a complex figure who was both a cold-blooded killer in the eyes of the law and a folk hero to many, particularly the downtrodden Hispanic population of New Mexico, who saw him as a champion against corrupt authority.

His story, embellished and romanticized over time, speaks to the allure of the outlaw, the defiance of a young man against a world that offered him little. The "McCarty Gang," then, is not a footnote, but the very prologue to one of the most compelling narratives of the American frontier – the journey of a forgotten boy named Henry McCarty who, through a series of desperate alliances and a life lived on the run, became an indelible part of history, forever known as Billy the Kid.