The Enduring Echoes of Pecos Pueblo: A Story of Trade, Resilience, and Legacy

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

The wind whispers through the towering ponderosa pines that crown the mesas of northern New Mexico, carrying with it the dust of centuries. Beneath the vast, cerulean sky, the crumbling adobe walls of Pecos Pueblo stand as a silent testament to a civilization that once thrived, a vibrant crossroads of cultures and commerce. Today, the Pecos National Historical Park preserves these evocative ruins, inviting visitors to walk among the ghosts of a people whose story is one of remarkable resilience, devastating decline, and an enduring legacy that challenges our understanding of extinction.

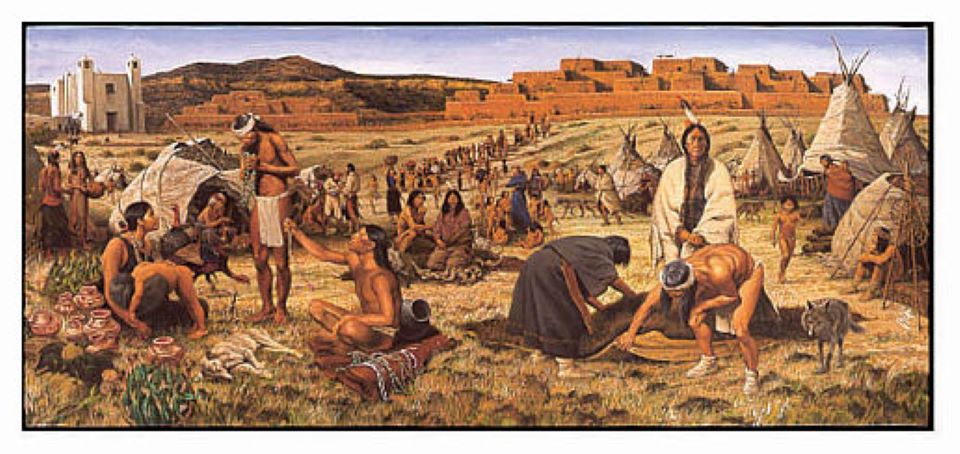

Pecos Pueblo, known to its people as Cicuye, was not merely a village; it was a bustling metropolis, a strategic fortress, and a vital economic hub in the pre-Columbian Southwest. Situated at the easternmost edge of the Pueblo world, guarding the vital Glorieta Pass, Pecos was ideally positioned to serve as the primary intermediary between the agricultural Pueblo peoples of the Rio Grande Valley and the nomadic Plains tribes – the Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa.

The Golden Age: A Crossroads of Cultures

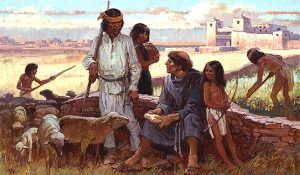

For centuries before the arrival of Europeans, Pecos was a dynamic center of trade. Its multi-story adobe and stone dwellings, some reaching five stories high, housed a population estimated to be between 2,000 and 3,000 at its peak in the 15th and early 16th centuries. "Pecos was arguably the largest and most powerful of the Eastern Pueblos," notes a National Park Service historian. "Its location made it indispensable for both the Pueblo people and the Plains tribes."

The Pecos people, skilled farmers, cultivated corn, beans, and squash in the fertile valley of the Pecos River. They also produced distinctive pottery, cotton blankets, and turquoise jewelry. These goods were traded for the bounty of the Plains: bison hides, dried meat (jerky), salt, and even slaves. The legendary cibola trade, the exchange of buffalo products, flourished here, enriching Pecos and forging complex social and economic ties across vast distances.

Life in Pecos was structured around communal living and deep spiritual beliefs. Kivas, circular subterranean ceremonial chambers, dotted the plazas, serving as sacred spaces for rituals, gatherings, and the perpetuation of ancient traditions. The Pecos people were known for their adaptability and their formidable defensive capabilities, often repelling raids from various tribes seeking to control the lucrative trade routes. Their strategic location and military prowess allowed them to maintain a degree of autonomy and prosperity unmatched by many of their neighbors.

The Spanish Shadow: Disease and Domination

The arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century marked the beginning of Pecos’s long and tragic decline. Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s expedition first encountered Pecos in 1540, marveling at its size and complexity. His chroniclers described it as a "very large pueblo, strong, and well fortified." Initially, the relationship was tentative, but with the establishment of the Spanish colony of New Mexico in 1598, Pecos, like all Pueblos, fell under the dominion of the Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church.

A Franciscan mission, Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Porciúncula de Pecos, was established in the early 17th century, its massive adobe church towering over the ancient pueblo. While the friars brought new technologies and crops, they also brought disease, forced labor, and an aggressive suppression of indigenous spiritual practices. The Pecos people were compelled to build the mission church, work in Spanish fields, and abandon their traditional ceremonies. This cultural clash bred deep resentment, simmering beneath the surface.

The devastating impact of European diseases, to which the indigenous population had no immunity, cannot be overstated. Smallpox, measles, and influenza swept through Pecos repeatedly throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, decimating its population. "Epidemics were like waves, each one further eroding the community’s strength," writes archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett, who conducted early excavations at Pecos. "A population of thousands dwindled to hundreds within a few generations."

Pecos played a significant role in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, a unified uprising that temporarily expelled the Spanish from New Mexico. The Pecos warriors fought bravely, contributing to the initial success of the revolt. However, Spanish re-conquest in the 1690s brought renewed subjugation and further hardship.

The Decline: A Multifaceted Collapse

By the 18th century, Pecos faced a perfect storm of challenges. The relentless waves of disease continued to weaken the community. The population, once numbering in the thousands, plummeted to just a few hundred. This demographic collapse left them vulnerable to external threats.

The rise of the Comanche on the Plains in the mid-18th century proved particularly devastating. The Comanches, now powerful and mobile thanks to the horse, disrupted the traditional trade networks that had sustained Pecos for centuries. They began to raid Pecos directly, stealing crops, horses, and taking captives. The very location that had once been Pecos’s greatest asset – its eastern frontier position – became its greatest vulnerability.

"Pecos became a buffer state, constantly under siege," explains a park ranger during a historical tour. "They were caught between the Spanish and the Plains tribes, losing people and resources on all fronts." Agriculture became precarious, and the community struggled to maintain its defenses and cultural integrity. By the early 19th century, the once-mighty pueblo was a shadow of its former self, its great plazas largely empty, its multi-story dwellings crumbling.

The Final Migration: A Journey of Survival

The story of Pecos culminates in a poignant act of survival and cultural absorption. By 1838, after another severe smallpox epidemic, only 17 Pecos survivors remained. Facing insurmountable odds – constant Comanche raids, dwindling resources, and an inability to maintain their community or perpetuate their traditions – they made a momentous decision.

Rather than face complete annihilation, they sought refuge with their linguistic relatives, the Towa-speaking people of Jemez Pueblo, located approximately 80 miles to the west. On a cold winter day in 1838, the last 17 Pecos people embarked on their final journey, leaving behind their ancestral home forever. They carried with them what little they could, but more importantly, their memories, their traditions, and their spiritual beliefs.

The Jemez people welcomed them, offering them land, shelter, and a new beginning. While the Pecos language eventually faded, absorbed by the dominant Towa language of Jemez, the cultural identity and historical memory of Pecos were carefully preserved. "They didn’t just vanish," says a Jemez elder, whose ancestors welcomed the Pecos. "They became part of us. Their stories are our stories now."

One of the most enduring legends associated with the Pecos migration is that of the "Pecos Bull." It is said that the Pecos people kept a living buffalo, or a large bison effigy, in a kiva, symbolizing their deep connection to the Plains and their role in the bison trade. While perhaps embellished over time, this legend speaks to the profound spiritual and economic ties that defined Pecos for centuries.

The Archaeological Legacy: Unearthing the Past

Today, the ruins of Pecos Pueblo are a National Historical Park, meticulously preserved and studied. The site gained prominence in the early 20th century through the pioneering archaeological work of Alfred V. Kidder, who conducted extensive excavations from 1915 to 1929. Kidder’s meticulous methodology, including stratigraphic excavation and detailed record-keeping, revolutionized Southwestern archaeology. His work at Pecos provided an unprecedented understanding of Pueblo prehistory, settlement patterns, and cultural change over more than a millennium.

The archaeological record at Pecos is remarkably rich, offering insights into daily life, trade networks, religious practices, and the devastating impact of colonialism and disease. Visitors can explore the foundations of the ancient pueblo, walk through the ruins of the massive mission church, and reflect on the lives lived within those walls. The site serves as a powerful outdoor museum, a place where history speaks through the stones and the silence.

An Enduring Presence

While Pecos Pueblo as a distinct political and cultural entity ceased to exist in 1838, the story of the Pecos people is far from over. Their descendants live on at Jemez Pueblo, where the memory of Pecos is cherished and honored. Annual pilgrimages are sometimes made to the ancestral site, connecting current generations to their ancient homeland.

The story of Pecos is a profound reminder of the fragility of even the most resilient civilizations in the face of overwhelming external pressures. It is a testament to the devastating power of disease and the complexities of intertribal and intercultural relations. Yet, it is also a story of adaptation, perseverance, and the enduring human spirit.

As the sun sets over the Pecos Valley, casting long shadows across the ancient walls, one can almost hear the echoes of a vibrant past – the chatter of traders, the sounds of ceremonies, the laughter of children. Pecos Pueblo may be gone, but its spirit endures, woven into the fabric of the land and the living traditions of the Jemez people, a powerful narrative of a civilization that, though transformed, refused to be forgotten. The wind still whispers, and in its breath, the story of Pecos lives on.