The Enduring Enigma of Roanoke: America’s First Lost Colony

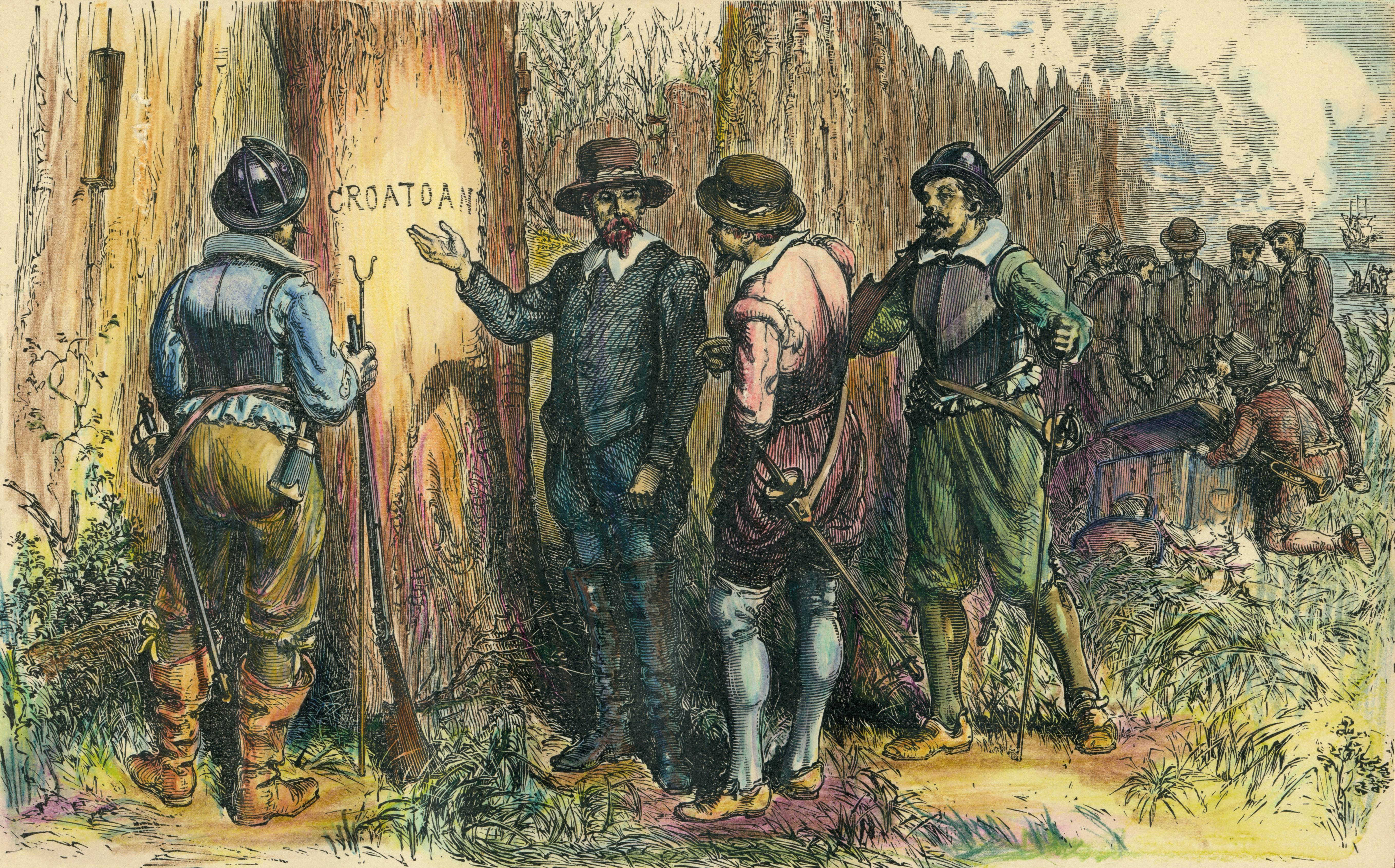

Roanoke Island, North Carolina, 1590. The air hung heavy with the scent of salt and pine, but an unnatural silence permeated the small English settlement. Three years had passed since Governor John White had reluctantly departed for England, leaving behind his daughter, granddaughter Virginia Dare – the first English child born in the Americas – and 115 other hopeful colonists. He returned to find not a bustling community, but a ghostly tableau of abandonment. The houses were gone, dismantled. The palisade, erected for defense, was likewise absent. The only clues were two cryptic carvings: "CROATOAN" etched neatly into a gatepost, and the letters "CRO" crudely carved into a nearby tree. There was no cross, the prearranged signal for distress. The colonists had vanished.

This chilling discovery marked the birth of America’s oldest and most persistent unsolved mystery: the Lost Colony of Roanoke. For over four centuries, historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts have grappled with the fate of these intrepid pioneers, sifting through scant evidence, folklore, and countless theories. Their disappearance remains a potent symbol of the perils of early colonial ambition, a haunting whisper across the Outer Banks, and a testament to the enduring power of the unknown.

A Dream of Empire: Raleigh’s Vision

The story of the Lost Colony begins not on Roanoke Island, but in the grand courts of Elizabethan England. Queen Elizabeth I, the "Virgin Queen," harbored ambitions of establishing an English foothold in the New World, challenging Spain’s dominance and securing valuable resources. Sir Walter Raleigh, a dashing courtier and adventurer, was granted a patent in 1584 to explore and colonize lands in North America, which he named "Virginia" in honor of his queen.

Raleigh’s initial expeditions were exploratory, scouting the coastlines and establishing contact with local Native American tribes. An early attempt at a military colony in 1585, led by Ralph Lane, proved disastrous. Plagued by poor planning, dwindling supplies, and escalating conflicts with the Roanoke Indians, the colonists abandoned the settlement in 1586, hitching a ride back to England with Sir Francis Drake. This initial failure, however, did not deter Raleigh. He envisioned a more permanent, agrarian settlement – one that included families – to truly lay claim to the vast new territory.

The Ill-Fated Voyage of 1587

In the spring of 1587, a new expedition set sail, comprised of approximately 117 men, women, and children. Unlike the previous military venture, this was a civilian colony, intended to be self-sufficient and establish a thriving English presence. John White, an artist and cartographer who had been part of the 1585 expedition and had meticulously documented the land and its inhabitants, was appointed governor. His detailed watercolor paintings offer invaluable glimpses into the lives of the Algonquian people and the natural landscape of the region.

The colonists’ original destination was the Chesapeake Bay, a more favorable location further north. However, their pilot, Simon Fernandez, a contentious figure, allegedly refused to sail further, forcing the weary settlers to disembark on Roanoke Island – the site of the previous failed colony. This change of plans immediately put the new colony at a disadvantage, placing them in an area where relations with local tribes were already strained due to past conflicts.

Despite these initial setbacks, the colonists set about building their homes and fort. On August 18, 1587, a momentous event occurred: Virginia Dare was born to Eleanor White Dare, Governor White’s daughter, and Ananias Dare. She was the first English child born in North America, a symbol of hope and the future for the nascent colony.

Within weeks, however, the precariousness of their situation became apparent. Supplies were running low, and the hostility of some local tribes made foraging dangerous. The colonists implored Governor White to return to England for provisions and reinforcements. Reluctantly, and with a heavy heart, White agreed, leaving his family and the entire colony behind. Before his departure, a crucial agreement was made: if the colonists were forced to move, they would carve the name of their new destination into a tree or post. If they were in distress, they would add a cross above the carving.

The Long Silence: White’s Delayed Return

John White’s journey back to England was fraught with difficulty, but his return proved even more challenging. He arrived in a nation consumed by a looming threat: the Spanish Armada. England was mobilizing all its ships and resources to defend against the mighty Spanish fleet. White’s desperate pleas for a relief mission were repeatedly denied; no ships could be spared for a distant colony when the very survival of England was at stake.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 was a monumental victory for England, but it meant further delays for White. It wasn’t until August 1590 – three agonizing years after his departure – that White finally secured passage on a privateering expedition bound for the West Indies, which agreed to make a detour to Roanoke.

His arrival on Roanoke Island on August 18, 1590, Virginia Dare’s third birthday, delivered the crushing blow. The settlement was deserted. The only clues were the word "CROATOAN" on the gatepost and "CRO" on the tree. There was no cross, which, according to their agreement, indicated that the colonists had not been in distress. Croatoan was the name of a nearby island (modern-day Hatteras Island) inhabited by a friendly Native American tribe led by Chief Manteo, who had been baptized an English lord. White desperately wanted to sail to Croatoan, but a violent storm, coupled with the reluctance of the ship’s captain, thwarted his efforts. He never saw his family or the other colonists again.

Theories and Speculations: Unraveling the Threads

The immediate aftermath of White’s discovery spawned a flurry of theories, none of which could be definitively proven. Over the centuries, these theories have evolved, informed by new archaeological findings, historical documents, and scientific analysis.

-

Assimilation with Native Americans (The Most Popular Theory): This is the most widely accepted and enduring theory. Given the "CROATOAN" carving and the absence of a distress signal, many historians believe the colonists, facing dwindling supplies and hostile tribes, sought refuge with the friendly Croatoan people. They may have integrated into the tribe, intermarried, and gradually lost their distinct English identity.

- Supporting Evidence: Oral traditions among the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina speak of European ancestry and connections to the Roanoke colonists. Some Lumbee family names (like Dial, Goins, Sampson) are remarkably similar to those of the Lost Colonists. Archaeological digs on Hatteras Island have uncovered 16th-century English artifacts, including a signet ring, sword hilt, and copper pieces, suggesting a European presence among the Croatoans.

- Quote: Historian Lee Miller, author of "Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony," suggests, "The most likely scenario is that they moved inland and slowly assimilated into Native American culture."

-

Massacre by Hostile Tribes: Another prevalent theory suggests a violent end. The Powhatan Confederacy, a powerful group led by Chief Powhatan (father of Pocahontas), was known for its expansionist tendencies and hostility towards European encroachment. Some accounts from early Jamestown settlers claimed that Powhatan had ordered the killing of the Roanoke colonists.

- Supporting Evidence: Captain John Smith of Jamestown later reported that Powhatan claimed to have slaughtered the Roanoke colonists, though this was likely a boast to intimidate the new English settlers. There are no direct archaeological findings to support a large-scale massacre at Roanoke.

- Quote: John Smith recorded Powhatan’s alleged boast: "He had been at the murder of that Colony and had there found some of their guns."

-

Starvation, Disease, or Environmental Disaster: Early colonial life was incredibly harsh. It’s plausible that the colonists succumbed to disease, starvation, or a combination of factors. Recent research has added weight to the "environmental disaster" aspect.

- Supporting Evidence: Tree-ring data analyzed in the early 2000s revealed that the colonists arrived during the worst drought in 800 years for the region. This would have severely impacted their ability to grow crops, find fresh water, and hunt, making survival incredibly difficult.

- Fact: The Jamestown colony, established just two decades later, also experienced devastating "starving times."

-

Relocation to Another Site: The colonists might have attempted to move further inland, perhaps to the Chesapeake Bay area as originally planned, or to another more fertile location. They could have encountered difficulties during this journey, getting lost or falling victim to the elements or hostile encounters.

- Supporting Evidence: Some maps from the period, including one drawn by White himself, show symbols suggesting an inland fort or settlement. The "Site X" and "Site Y" archaeological digs (later renamed by researchers) further inland in Bertie County, North Carolina, have uncovered 16th-century English and Native American artifacts, hinting at a potential relocation site.

Modern Investigations and Lingering Clues

The allure of the Lost Colony continues to drive modern archaeological and historical research.

- Archaeological Digs: Ongoing excavations at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island continue to uncover remnants of the 1585 military colony, but no definitive evidence of the 1587 civilian settlement or its fate. More promising are digs further inland, like those conducted by the First Colony Foundation. At sites near Salmon Creek in Bertie County, archaeologists have unearthed fragments of English pottery, metal objects, and evidence of interactions between Europeans and Native Americans from the late 16th century, potentially hinting at a group of colonists who moved inland.

- Genetic Research: DNA analysis of descendants of local Native American tribes and early European settlers could one day provide genetic links to the Lost Colonists, though tracing such ancient lineages is incredibly complex.

- The Dare Stones: A series of engraved stones discovered in the 1930s, purportedly written by Eleanor Dare, claiming the colonists had moved inland and were later massacred. While initially hailed as a breakthrough, the majority of these stones were later exposed as hoaxes, though the first stone’s authenticity remains debated by a few.

- The "Lost Colony" Play: Since 1937, "The Lost Colony," an outdoor symphonic drama, has been performed annually on Roanoke Island, keeping the story alive for millions of visitors and cementing its place in American folklore.

The Enduring Power of the Unexplained

The Lost Colony of Roanoke remains an open wound in the fabric of American history, a riddle wrapped in an enigma. It symbolizes the fragility of human endeavor, the harsh realities of colonial expansion, and the often-overlooked resilience of Native American cultures.

Perhaps there will never be a definitive answer. The evidence is too sparse, the passage of time too vast. Yet, the mystery continues to captivate precisely because it is unsolved. It invites us to imagine, to speculate, to connect with the ghosts of those lost pioneers who embarked on a dream and vanished into the wilderness. Their story reminds us that even in an age of advanced technology, some secrets of the past steadfastly refuse to be unearthed, leaving us with a profound sense of wonder and the enduring enigma of America’s first lost dream. The whispers across the Outer Banks continue, asking the same question that haunted John White over four centuries ago: Where did they go?