The Enduring Legend of the Oregon Trail: A Journey Through Danger and Hardship that Forged a Nation

America is a nation woven from legends, tales of courage, exploration, and the relentless pursuit of a dream. Few narratives resonate as deeply within the national consciousness as that of the Oregon Trail. It’s a legend of epic proportions, painted with the broad strokes of Manifest Destiny and the pioneering spirit. Yet, beneath the romanticized veneer lies a stark reality: a brutal, unforgiving odyssey through a vast wilderness, where danger was omnipresent, hardship was the daily bread, and the cost in human lives was staggering. The Oregon Trail was not merely a path; it was a crucible that forged the character of a nation, one agonizing mile at a time.

From the early 1840s to the late 1860s, an estimated 400,000 brave, desperate, or simply hopeful souls embarked on this monumental westward migration. Their journey began in bustling frontier towns like Independence or St. Joseph, Missouri, a "jumping off" point where the familiar world ended and the great unknown began. Here, families from diverse backgrounds—farmers, merchants, adventurers—converged, their wagons laden with supplies, their hearts brimming with optimism and a healthy dose of apprehension. They sought fertile lands in the Willamette Valley, the promise of gold in California, or simply a fresh start, far from the economic downturns and crowded cities of the East.

The initial days on the trail, often following the Platte River, might have offered a deceptive sense of adventure. The vast, rolling prairies, dotted with wildflowers and herds of buffalo, could inspire awe. But this nascent optimism soon gave way to the relentless grind of reality. The journey, typically spanning four to six months and covering roughly 2,000 miles, was an exercise in sheer endurance. Wagons, often smaller "prairie schooners" rather than the romanticized Conestogas, lumbered along at a snail’s pace, pulled by oxen, mules, or sometimes horses. The rhythmic creak of axles, the shouts of teamsters, and the constant murmur of human voices formed the soundtrack of this arduous migration.

The Silent Killer: Disease and Despair

While the popular imagination often conjures images of fierce encounters with Native Americans or dramatic river crossings, the most insidious and prolific killer on the Oregon Trail was disease. Cholera, dysentery, smallpox, and typhoid fever swept through the wagon trains with terrifying speed, exacerbated by poor sanitation, contaminated water, and close living quarters. Cholera, in particular, was a swift and merciless executioner. A healthy person could be struck down and dead within hours, their body wracked by dehydration and fever.

"The road is lined with graves," wrote one weary pioneer in their diary, a sentiment echoed by countless others. It’s estimated that between 20,000 and 40,000 pioneers perished along the Oregon Trail, a grim tally that means a fresh grave could be found every 80 yards for much of the journey. Children were particularly vulnerable, their small bodies succumbing quickly to illness. Parents often had to bury their offspring in shallow, unmarked graves along the trail, a heartbreaking duty that left indelible emotional scars. The sheer volume of death, the constant presence of grief, and the need to push forward despite personal tragedy tested the limits of human resilience.

Nature’s Gauntlet: From Plains to Peaks

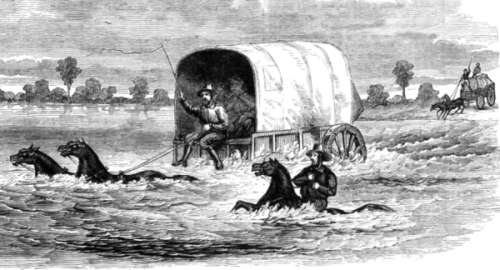

Beyond disease, the natural world itself presented an array of formidable dangers and hardships. The journey began with the relatively flat, but often muddy or dusty, Great Plains. Rain turned the earth into a sticky, impassable quagmire, while prolonged dry spells created choking clouds of dust that coated everything and everyone, irritating lungs and eyes. Rivers, from the meandering Platte to the treacherous Snake and Columbia, posed their own threats. Swollen by spring thaws or sudden rains, they became raging torrents, capable of overturning wagons, drowning livestock, and sweeping away entire families. Many pioneers learned to swim or fashioned makeshift ferries, but the river crossings remained one of the most feared segments of the journey.

As the emigrants pressed westward, the landscape grew more challenging. Deserts, like the formidable Sublette Cutoff, tested their resolve with their arid expanse, scorching heat, and scarcity of water and forage. Livestock, weakened by the journey, often collapsed from thirst and exhaustion. Wagons broke down, axles snapped, and wheels splintered on the rough terrain, necessitating arduous repairs or the abandonment of precious belongings.

Then came the mountains – the formidable Rockies and the Cascade Range. Ascending steep passes, often requiring the doubling of teams or the lowering of wagons by ropes down precipitous slopes, was backbreaking work. The weather in the mountains was unpredictable; sudden blizzards could trap wagon trains, leading to frostbite and starvation. The infamous "Blue Mountains" of Oregon, with their dense forests and steep trails, presented one of the final, grueling tests before the journey’s end.

The Human Element: Fear, Conflict, and Community

While exaggerated in popular lore, encounters with Native American tribes were a complex reality. For many tribes, the influx of pioneers represented an invasion of their ancestral lands, a threat to their way of life, and a depletion of vital resources like buffalo. While many interactions were peaceful, involving trade or guidance, tensions inevitably arose. Raids on livestock, skirmishes over water rights, and isolated attacks did occur, fueling the pioneers’ fear and solidifying a narrative of "Indian danger" that often overshadowed the devastating impact of westward expansion on Native American communities. For the emigrants, the wilderness was not empty; it was inhabited by people whose land they were traversing, often without permission.

Beyond external threats, the internal dynamics of the wagon trains themselves presented challenges. Months of close quarters, constant stress, and shared hardship inevitably led to friction. Disputes over leadership, accusations of selfishness, and personality clashes were common. Yet, these communities also demonstrated remarkable resilience and cooperation. When a wagon broke down, neighbors helped with repairs. When illness struck, fellow travelers offered what meager comfort and medical aid they could. The trail fostered a unique blend of individualism and communal dependency, where survival often hinged on the willingness to help one another.

Landmarks and the Promise of the End

Amidst the endless toil and danger, certain landmarks became beacons of hope and progress. Chimney Rock, a distinctive geological formation in present-day Nebraska, served as an unmistakable signpost, indicating that the journey was roughly one-third complete. Independence Rock in Wyoming, often called the "Great Register of the Desert," bore the carved names of thousands of pioneers, a testament to their passage and a collective shout of defiance against the wilderness. These sites offered brief respites, opportunities to rest, repair, and reflect on the distance covered and the challenges still ahead.

The final leg of the journey, particularly through the Columbia River Gorge, was a cruel paradox. The lush, verdant landscape signaled the proximity of Oregon, yet the terrain was some of the most difficult. Pioneers faced the terrifying prospect of floating their wagons down the treacherous Columbia on rafts or attempting the perilous "Barlow Road," a toll road that bypassed the river but involved steep descents and deep mud. For those who had endured months of plains and mountains, these final obstacles were a test of their very last reserves of strength and spirit.

The Legacy: Myth, Memory, and the Making of America

When the weary pioneers finally reached the Willamette Valley, they were met not with instant paradise, but with the arduous task of carving out a new life from the wilderness. Yet, they had done it. They had crossed a continent, faced down death, and forged a new path.

The legend of the Oregon Trail has since been woven into the fabric of American identity. It embodies the "pioneer spirit"—resilience, self-reliance, courage, and an unwavering belief in the future. It’s a story of ordinary people achieving extraordinary feats, driven by a dream.

However, it is crucial to remember that the legend is also a simplified narrative. It often glosses over the immense human cost, the environmental impact of such a massive migration, and the profound, often violent, displacement of Native American populations. The Oregon Trail was not just a route to opportunity; it was a pathway of conquest, forever altering the landscape and its original inhabitants.

Today, fragments of the Oregon Trail still exist – faint wagon ruts etched into the earth, historical markers, and museums that preserve the stories of those who dared to make the journey. These physical remnants serve as powerful reminders of the danger and hardship faced by the pioneers, a tangible connection to a past that shaped the very geography and spirit of the United States. The Oregon Trail remains a foundational American legend, a testament to the human capacity for endurance, sacrifice, and the relentless pursuit of a promised land, forever etched in the collective memory as a journey that, for better or worse, forged a nation.