The Enduring Paradox of Shakerism: A Legacy Forged in Simplicity and Sacrifice

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

In the verdant valleys and rolling hills of 19th-century America, amidst the fervor of religious revival and the burgeoning spirit of utopian experimentation, a peculiar and profoundly influential sect flourished: the Shakers. Officially known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, these were not merely spiritual seekers but radical social reformers whose commitment to communal living, gender and racial equality, pacifism, and ascetic simplicity left an indelible, if often misunderstood, mark on American history, culture, and design.

Today, the Shakers are virtually extinct, their numbers dwindling to a mere handful of adherents at their last active community in Sabbathday Lake, Maine. Yet, their legacy—manifested in their iconic furniture, their architectural purity, and their revolutionary social ideals—endures, prompting us to ponder the paradox of a people whose very principles of celibacy and withdrawal from the world ultimately led to their physical decline, even as their innovations continue to inspire.

The Genesis of a Radical Vision

The story of the Shakers begins in 18th-century England with Ann Lee, a textile worker from Manchester. Born in 1736, "Mother Ann," as she would come to be known, endured a series of personal tragedies, including the loss of all four of her children in infancy. These profound experiences, coupled with a deep spiritual awakening and her involvement with a dissenting Quaker group known for their ecstatic worship, led her to believe that lust was the root of all evil and that celibacy was the only path to salvation. She preached that God possessed both male and female characteristics, and that the "second appearing of Christ" would be in the form of a woman—herself.

Persecuted for her radical beliefs in England, Mother Ann and a small band of followers sailed for America in 1774, seeking religious freedom. They settled in Niskayuna (now Watervliet), New York, establishing their first communal settlement in 1776. Here, their distinctive worship practices—characterized by singing, dancing, and the "shaking" of their bodies to expel sin, which gave them their popular name—began to draw converts.

Foundational Principles: A Society Apart

What set the Shakers apart was not just their unique form of worship but their comprehensive and rigorously applied set of principles that governed every aspect of their lives.

- Celibacy: This was the cornerstone of Shaker belief. As Mother Ann declared, "To enter the Kingdom of Heaven, you must become as a little child; and to be as a little child, you must be pure from the flesh." For a society dependent on recruitment rather than natural increase, this was both their spiritual strength and their eventual demographic weakness.

- Communalism: Shakers lived in self-sufficient communities where all property was held in common. "Hands to work and hearts to God" was their guiding maxim. Every individual contributed their labor for the good of the collective, fostering an ethic of industry and shared prosperity.

- Gender and Racial Equality: Decades before the mainstream women’s suffrage movement, Shaker communities offered women leadership roles and equal status with men. Elders and Eldresses, often in pairs, governed the communities. Similarly, the Shakers welcomed African Americans, treating them with equality in a period marked by slavery and intense racial prejudice. This radical inclusivity made Shaker communities havens for those seeking a more just and equitable society.

- Pacifism: Shakers were staunch pacifists, refusing to participate in war or violence. This stance, particularly during the American Civil War, often put them at odds with the wider society but underscored their commitment to a peaceful, non-coercive existence.

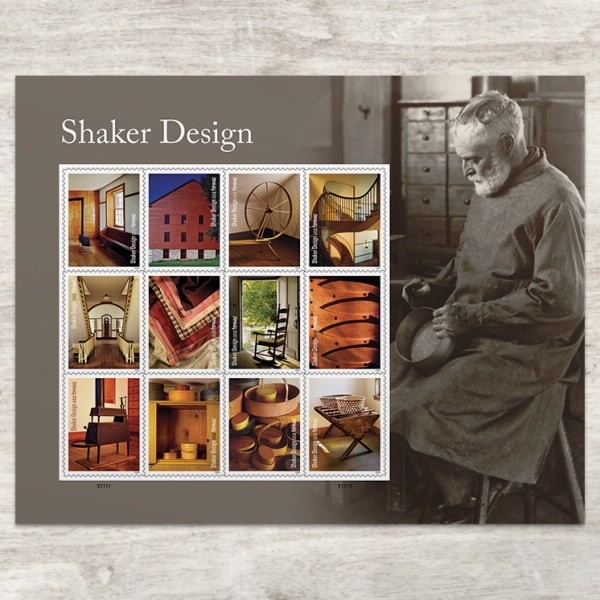

- Simplicity and Utility: Believing that "every force that generates beauty in architecture or in the human spirit is a force to be preserved," the Shakers lived by a philosophy of functional beauty. Their architecture, furniture, and household items were stripped of all unnecessary ornamentation, focusing on clean lines, perfect proportions, and meticulous craftsmanship. This aesthetic, often summarized as "form follows function," was not merely practical but deeply spiritual, reflecting their belief that God’s hand was in all useful work.

The Golden Age: Industry and Innovation

By the mid-19th century, Shakerism reached its zenith, boasting some 6,000 members across 18 major communities stretching from Maine to Kentucky. Their commitment to industry and innovation made them remarkably successful. Shaker villages were models of efficiency and ingenuity. They were among the first to package seeds in envelopes for sale, developed improved farm machinery, invented the clothespin, the circular saw, and many other practical tools. Their herbal medicines were widely renowned.

Their craftsmanship, however, remains their most enduring contribution to American culture. Shaker furniture, characterized by its elegant simplicity, durability, and ingenious design (like the peg rail for hanging chairs), is highly prized today. Each piece was crafted with spiritual devotion, a physical manifestation of their belief in perfection. As one Shaker elder reportedly said, "Do your work as though you had a thousand years to live, and as if you were to die tomorrow." This blend of timeless quality and spiritual intention resonates deeply with modern sensibilities, making Shaker design a precursor to minimalist and modern aesthetics.

The Inevitable Decline

Despite their success and innovative spirit, the seeds of the Shakers’ decline were sown within their core tenets. The most significant factor was, undoubtedly, celibacy. Without natural reproduction, the communities relied entirely on converts and, increasingly, on orphans they raised. As the 19th century drew to a close and the 20th century began, several forces conspired against their growth:

- Changing Societal Norms: The industrial revolution, the lure of individualism, and the increasing secularization of American society made the strictures of communal, celibate life less appealing.

- Reduced Need for Asylum: Shaker communities had once provided a safe haven for the poor, the widowed, and the disenfranchised. As state welfare systems and other social nets developed, the practical need for such communities diminished.

- Loss of Charismatic Leadership: After Mother Ann’s death in 1784, the sect was guided by a succession of strong leaders. However, the spiritual fervor of the early days became harder to sustain through generations.

- The World Intrudes: Despite their efforts to remain separate, the outside world, with its new technologies and ideas, inevitably seeped into Shaker life, offering alternatives to their rigid communal structure.

By the early 20th century, many Shaker communities had closed or consolidated. Buildings were sold off, and artifacts dispersed. The once-bustling villages became quiet testaments to a fading dream.

A Legacy That Endures

Today, the Shaker legacy lives on in several powerful ways. The preserved Shaker villages at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky; Hancock Shaker Village in Pittsfield, Massachusetts; and Shaker Village of Alfred, Maine, serve as living museums, allowing visitors to step back in time and experience the unique architecture, craftsmanship, and daily life of these remarkable people. These sites are vital for understanding American communal experiments and religious history.

Their design philosophy, in particular, has had a profound and lasting impact. The Shaker aesthetic of simplicity, utility, and honest craftsmanship directly influenced movements like Arts and Crafts, Scandinavian Modernism, and contemporary minimalist design. Designers and architects continue to draw inspiration from their elegant solutions to everyday problems, their focus on quality, and their belief that beauty emerges naturally from function.

Beyond design, the Shakers’ radical commitment to social justice—gender equality, racial equality, and pacifism—remains a powerful reminder of what a community founded on deeply held moral principles can achieve, even if only for a time. They demonstrated that an alternative to the hierarchical, individualistic, and often violent norms of their era was not only possible but could flourish.

The Shaker story is a poignant one, a testament to the human yearning for perfection, community, and spiritual truth. Their choice of celibacy, while ensuring their purity, also sealed their fate as a dwindling people. Yet, in their quiet discipline, their ingenious creations, and their unwavering faith, the Shakers forged a legacy that transcends their physical disappearance. They remind us that true value often lies not in accumulation or power, but in simplicity, purpose, and the profound beauty of a life lived with "hands to work and hearts to God." The vibrant echoes of their past continue to resonate, inviting us to reflect on our own values and the enduring quest for a more harmonious world.