The Ever-Unfolding Scroll: Embracing the "Newness" in America’s Legends

When we speak of legends, our minds often drift to the ancient, to tales etched in the stone of millennia-old cultures – the sagas of Norse gods, the epic journeys of Greek heroes, or the intricate mythologies of India and China. America, a nation barely a quarter-millennium old, might seem to lack such venerable depths. Yet, to dismiss its legendary landscape is to miss a crucial, vibrant truth: American legends are defined not by their antiquity, but by their profound and persistent "newness." This isn’t a deficiency; it’s a dynamic, ever-unfolding characteristic that makes its myths uniquely resonant and perpetually relevant.

This "na zunilegend newness" – the inherent and often deliberate freshness of its legendary narratives – manifests in several compelling ways. It’s found in the constant creation of new heroes and villains, the swift evolution of existing tales, the reclaiming and reinterpretation of older, often marginalized narratives, and the astonishing speed with which technology can forge entirely new mythologies. America’s legends are less about a fixed past and more about a continuous present, shaped by a sprawling geography, a restless spirit, and an insatiable appetite for the extraordinary.

The Ancient Roots, Newly Reclaimed:

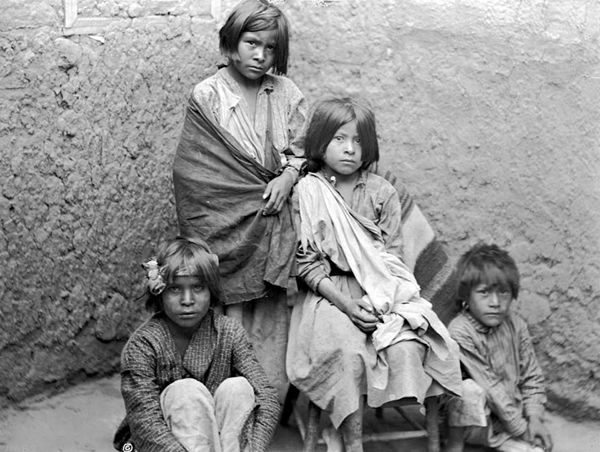

While the United States as a political entity is young, the North American continent boasts a tapestry of legends as ancient and profound as any on Earth. Indigenous American cultures have nurtured complex cosmologies, creation stories, and heroic narratives for thousands of years. These tales – from the Thunderbird’s mighty wings to the trickster Coyote’s cunning, from the Earth Diver myths of the Southeast to the Raven stories of the Pacific Northwest – are the true bedrock of American legend.

For centuries, these narratives were often ignored, suppressed, or relegated to academic curiosities by the dominant settler culture. However, in recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence and re-evaluation. Native American storytellers, scholars, and artists are actively reclaiming and sharing these traditions, giving them a "newness" not in their essence, but in their visibility and the respect they now command within the broader national consciousness. This re-centering of indigenous voices is a vital part of understanding America’s legendary landscape, moving beyond the colonial lens to embrace the true depth of its pre-contact history. As Laguna Pueblo writer Leslie Marmon Silko eloquently stated in Storyteller, "I will tell you something about stories… They aren’t just entertainment. Don’t be fooled. They are all we have, you see, to fight off illness and death. You don’t have anything if you don’t have the stories." This highlights the enduring, vital "newness" of their re-discovery by a wider audience.

Forging a Nation: The Deliberate Construction of Heroes:

Following European settlement, America faced a unique challenge: a vast, wild continent with no ancient kings or established national heroes to rally around. The solution was to create them. Many of America’s foundational legends were deliberately constructed or heavily embellished to serve the nascent nation’s need for identity, virtue, and inspiration.

Take George Washington and the cherry tree. This apocryphal tale, popularized by Mason Locke Weems in his 1800 biography, "The Life of Washington," was entirely fabricated. Weems, a clergyman, invented the story to illustrate Washington’s unimpeachable honesty, stating, "I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet." This wasn’t an ancient myth passed down through generations; it was a brand-new legend, crafted with journalistic intent to instill moral values and lionize a national figure.

Similarly, figures like Paul Revere, though a real historical person, were elevated to legendary status through poetic license. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1860 poem, "Paul Revere’s Ride," cemented his iconic status, simplifying complex historical events into a thrilling, patriotic narrative that resonated with a nation grappling with the impending Civil War. The "newness" here is the intentional crafting of heroes for a new nation, often blurring the lines between fact and inspiring fiction.

The Frontier’s Fables: Titans of the Untamed Land:

As the nation expanded westward, encountering vast, untamed wilderness and monumental challenges, a new breed of legend emerged: the larger-than-life frontier hero. These tales, born in logging camps, on railroad lines, and in the great plains, were often exaggerated to reflect the scale of the land and the audacity of those who sought to conquer it.

Paul Bunyan, the colossal lumberjack with his blue ox Babe, is a prime example. Originating in oral traditions of lumberjacks in the late 19th century, his stories were first published in print in 1910 by James MacGillivray and later popularized by advertising copywriter W.B. Laughead in 1916 for the Red River Lumber Company. Bunyan’s "newness" is that he is a distinctly modern legend, born of industrial labor and commercial promotion, embodying the strength, ingenuity, and sheer scale of American expansion. He didn’t exist in ancient folklore; he was created to explain the vastness of the forests and the incredible feats of early American industry.

Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman) is another figure whose life blended into legend. A real person who traveled across the Midwest planting apple seeds, his story was romanticized into a gentle, nature-loving pioneer, a symbol of American benevolence and westward settlement. The "newness" here lies in the rapid transformation of a historical figure into an archetypal myth, reflecting a burgeoning national identity rooted in agriculture and self-sufficiency.

The Call of the Wild and the Unexplained: Cryptids and Conspiracies:

America’s vast, often sparsely populated landscapes – from the misty forests of the Pacific Northwest to the arid deserts of the Southwest – have provided fertile ground for legends of the unknown. These tales tap into humanity’s primal fear and fascination with what lies beyond the edges of civilization, and they are constantly being refreshed and reimagined.

Bigfoot, or Sasquatch, is arguably America’s most famous cryptid. First documented extensively in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with earlier indigenous tales of wild men, the legend exploded in the mid-20th century with blurry photographs and alleged sightings. The "newness" of Bigfoot lies in its enduring appeal in the age of science and technology. Despite constant debunking, the legend persists, fueled by new alleged evidence, documentaries, and internet forums. It’s a modern mystery, continually re-investigated and kept alive by a blend of folklore and digital-age curiosity.

The Roswell Incident of 1947, involving a supposed UFO crash in New Mexico, similarly exemplifies this "newness." What began as a mundane weather balloon crash (according to official reports) quickly evolved into a full-blown legend of alien visitation and government cover-up. Its "newness" is that it’s a post-World War II phenomenon, born of the Cold War’s anxieties, the dawn of the Space Age, and a burgeoning mistrust of authority. Each new piece of alleged evidence, each declassified document, each new witness testimony, breathes fresh life into the Roswell myth, making it a legend that continually updates itself.

The Digital Age: Legends Born at the Speed of Light:

Perhaps the most striking manifestation of "na zunilegend newness" is seen in the digital age. The internet has become a hyper-accelerated myth-making machine, capable of birthing, disseminating, and evolving legends at unprecedented speeds.

The Slender Man is the quintessential example. Created in 2009 by Eric Knudsen on the Something Awful forums as part of a Photoshop contest, Slender Man quickly escaped its digital confines. Within years, he moved from internet creepypastas to video games, independent films, and even, tragically, real-world crimes. The "newness" of Slender Man is breathtaking: a legend with a known origin point, conceived purely for artistic and entertainment purposes, that rapidly achieved the viral spread and cultural impact typically reserved for ancient myths. He demonstrates that a legend no longer needs centuries to ferment; it can be born in a single online post and achieve global recognition almost overnight.

Urban legends, too, thrive in this environment. Tales of alligators in sewers, of phantom hitchhikers, or of specific local hauntings are no longer confined to word-of-mouth. They spread through email chains, social media posts, and viral videos, constantly adapting to new technologies and anxieties. This continuous re-packaging and re-telling ensures their "newness" and relevance to each successive generation.

The Legendary Idea: America as a Living Myth:

Beyond specific characters or events, America itself often functions as a living legend, an idea constantly being reimagined and redefined. The "American Dream" – the belief that anyone, regardless of background, can achieve success through hard work – is perhaps the nation’s most powerful and enduring legend.

Born from Enlightenment ideals and nurtured through waves of immigration, the American Dream is not a static concept. It has evolved from the promise of land and self-sufficiency to industrial opportunity, suburban prosperity, and now, often, the challenge of economic mobility in a globalized world. Its "newness" is in its constant re-evaluation and adaptation, reflecting the hopes, struggles, and aspirations of each generation. It’s a legend that is continually being written by the lives of millions, celebrated, critiqued, and fiercely debated. As Martin Luther King Jr. articulated in his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech, the dream is an ongoing pursuit, a vision that, though rooted in the nation’s founding principles, is perpetually seeking its fullest realization.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Story:

America’s legends are not dusty relics of a bygone era. They are a vibrant, living testament to a nation in perpetual motion, a culture that constantly invents, adapts, and reinterprets its stories. The "na zunilegend newness" of American myths is not a sign of immaturity, but of an extraordinary vitality. It reflects a nation still defining itself, still grappling with its past, and always looking toward a future ripe for new narratives.

From the ancient wisdom of indigenous peoples to the digitally born horrors of the internet age, from the deliberately crafted heroes of nation-building to the enduring quest for the American Dream, the legendary landscape of the United States is an ever-unfolding scroll. It reminds us that legends are not just about what once was, but about what is being created right now, and what will continue to be imagined tomorrow. In America, the greatest stories are always, in some profound way, just beginning.