The Fire in the Desert: Luis Oacpicagigua and the Pima Revolt of 1751

The sun beat down relentlessly on the arid lands of what is now northern Sonora, Mexico, and southern Arizona. For decades, this region, known to the Spanish as the Pimería Alta, had been a frontier of encounter, a crucible where the ancient ways of the O’odham (Pima) people clashed with the expansionist ambitions of the Spanish Empire. It was a slow burn, fueled by cultural imposition, economic exploitation, and a gnawing sense of injustice. But in November 1751, the smoldering embers of discontent ignited into a full-blown conflagration – a violent, desperate uprising led by a charismatic Pima leader named Luis Oacpicagigua.

Often relegated to a footnote in the grand narrative of colonial conquest, the Pima Revolt was a pivotal moment, a stark illustration of indigenous resistance against overwhelming odds. It shook the foundations of Spanish control in the far north, revealing the fragility of their grip and forcing a re-evaluation of their missionary and military strategies.

A Powder Keg in the Pimería Alta

By the mid-18th century, the Spanish presence in the Pimería Alta was deeply entrenched, yet perpetually precarious. Jesuit missionaries, spearheading the spiritual conquest, had established a chain of missions that served as centers of evangelization, but also as engines of social and economic transformation. Indigenous people were drawn to the missions by promises of protection from Apache raids, access to new tools and agricultural methods, and spiritual salvation. However, this came at a heavy price.

Mission life was a radical departure from traditional O’odham ways. Communal lands were transformed into mission fields, worked by forced indigenous labor under the supervision of the padres. Traditional religious practices were suppressed, and spiritual leaders often punished. Diseases, brought by the Europeans, decimated native populations, eroding their societal structures and trust in the newcomers’ promises. The Spanish justice system often seemed arbitrary and biased, favoring Spanish settlers over native grievances.

"The padres, while perhaps well-intentioned in their zeal to save souls, often became de facto civil administrators and even military commanders," notes historian John L. Kessell. "They demanded labor, enforced rigid moral codes, and often wielded considerable temporal power, which inevitably led to friction."

Beyond the missions, Spanish settlers and miners were encroaching on traditional Pima lands, diverting water resources crucial for their sustenance. The repartimiento system, which forced natives to work in mines or on Spanish haciendas, further fueled resentment. The Pima, accustomed to a life of relative autonomy and self-sufficiency, felt increasingly hemmed in, their culture eroded, their dignity challenged.

The Rise of Luis Oacpicagigua

Into this volatile environment stepped Luis Oacpicagigua, a man uniquely positioned to articulate and channel the growing Pima grievances. Born in Sáric, a mission community in what is now Sonora, Luis was no ordinary Pima. He had served the Spanish as a fiscal, a native assistant within the mission system, giving him an intimate understanding of Spanish customs, language, and weaknesses. He had traveled to Mexico City, gaining a broader perspective of the colonial world and perhaps a deeper sense of the injustices faced by his people.

Luis was charismatic, intelligent, and deeply respected by his people. He was also a man of action, capable of inspiring loyalty and organizing resistance. For years, he had attempted to work within the Spanish system, bringing complaints about mistreatment, land usurpation, and the abuse of power by Spanish officials and even some missionaries, to no avail. His petitions often fell on deaf ears or were dismissed as the complaints of "unruly Indians."

"Luis was a complex figure," writes historian David H. Hornbeck. "He was a product of both worlds – the indigenous and the Spanish – which made him both a bridge and, ultimately, a fulcrum for rebellion. He saw the hypocrisy and the broken promises firsthand."

By 1751, Luis had grown disillusioned with the Spanish promises of justice and equality. He saw that the only way to reclaim their lands, their culture, and their dignity was through force. Secretly, he began to rally various Pima communities, from the Gila River in the north to the valleys of Sonora in the south. He appealed to their shared heritage, their common grievances, and their desire for freedom.

The Fire Erupts: November 20, 1751

The spark that ignited the widespread revolt came on November 20, 1751. The timing was deliberate, coinciding with the Feast of the Presentation of Mary, when many Spanish settlers and missionaries would be gathered in mission churches, making them vulnerable targets.

The initial attacks were swift and brutal. At Mission Saric, where Luis resided, he reportedly led the assault that killed Padre Ignacio Keller and several Spanish families. Simultaneously, coordinated attacks erupted across the Pimería Alta. Padres, Spanish soldiers, settlers, and gente de razón (people of reason, referring to non-indigenous or Hispanized individuals) were targeted. Churches were ransacked, mission buildings burned, and livestock driven off.

The Pima, fighting with traditional weapons – bows and arrows, clubs, and some captured firearms – demonstrated a ferocity born of desperation. The element of surprise was key, and for a short time, they achieved considerable success. Estimates vary, but within the first few days, over 100 Spanish and mestizo settlers, including several missionaries, were killed. The revolt quickly spread, involving thousands of Pima warriors and their families.

"It was a coordinated uprising, meticulously planned by Luis, which speaks to his leadership and the depth of Pima resentment," noted a contemporary Spanish report, reflecting the shock and disbelief among colonial authorities. The Spanish had underestimated the Pima’s capacity for organized resistance.

Spanish Counter-Offensive and the Retreat of Rebellion

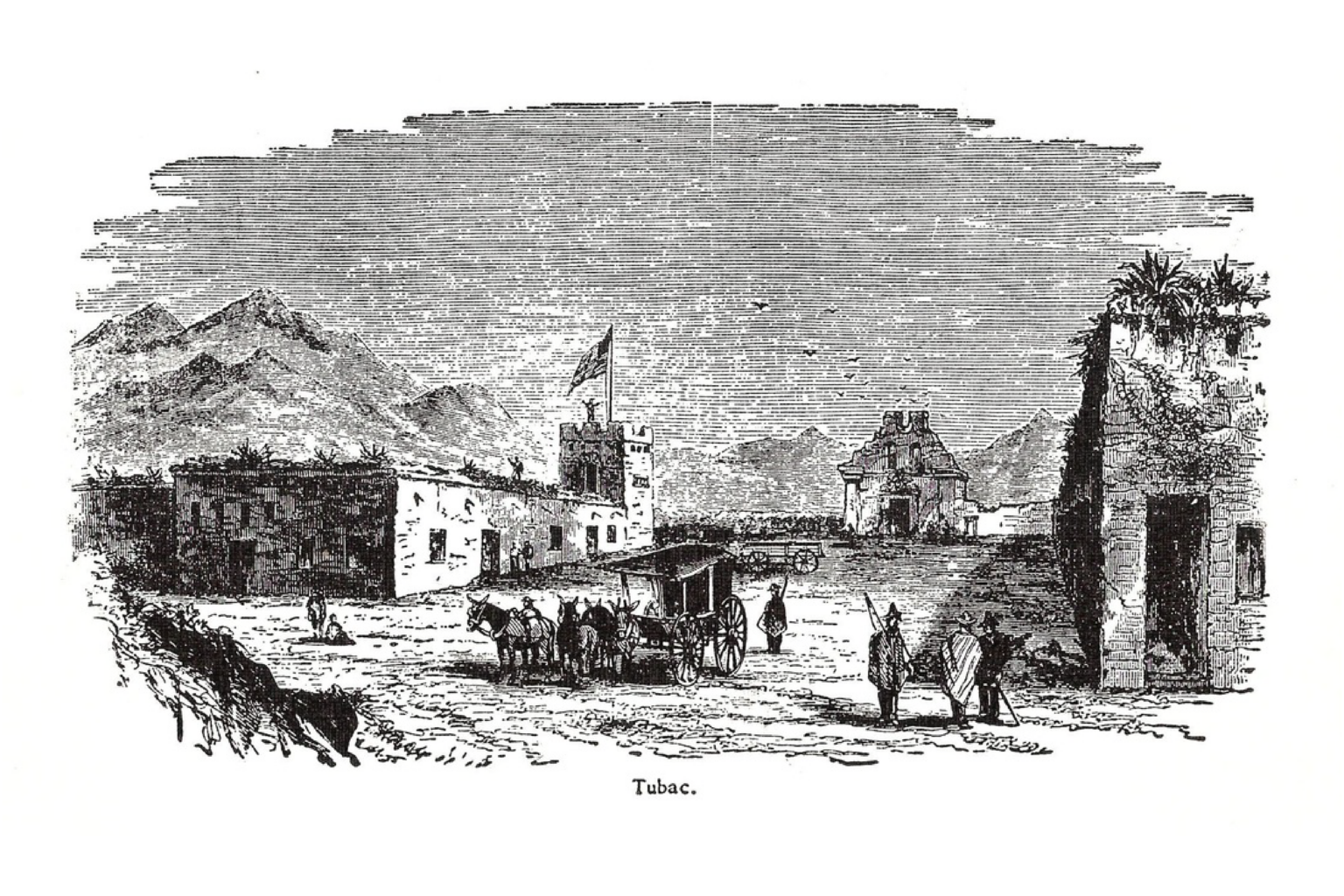

News of the revolt sent shockwaves through New Spain. Governor Diego Ortiz Parrilla, based in Sonora, immediately mobilized forces. From the presidios of Terrenate, Tubac, and Fronteras, Spanish soldiers, joined by allied Opata and Yaqui warriors, began their counter-offensive.

The Spanish military, though smaller in number than the combined Pima forces, possessed superior weaponry, training, and logistics. They also had the strategic advantage of controlling key water sources and fortified positions. The fighting was fierce and protracted. Pima warriors, though brave, often lacked the discipline and unified command to sustain a prolonged conventional war against the Spanish.

Luis, employing guerrilla tactics, skillfully led his forces, avoiding direct confrontations where possible and striking at isolated Spanish outposts. However, the Pima also faced internal divisions. Not all Pima communities joined the revolt, and some even sided with the Spanish, driven by old rivalries, fear of reprisal, or genuine loyalty to the missions. This internal fragmentation ultimately weakened the rebellion’s overall strength.

As the weeks turned into months, the Spanish systematically pushed back the Pima. They recaptured missions, executed suspected rebels, and launched punitive expeditions into Pima territory. The toll on the Pima was immense, with countless lives lost, villages burned, and crops destroyed.

The Fate of Luis and the Legacy of the Revolt

By early 1752, facing overwhelming Spanish military pressure and dwindling resources, Luis Oacpicagigua recognized the futility of continued armed resistance. In March 1752, he surrendered to Governor Parrilla, under the promise of a fair trial. The Spanish, eager to prevent him from becoming a martyr, initially spared his life.

Luis was imprisoned and eventually sent to San Juan de Ulúa, a notorious fortress prison on an island off Veracruz, where he likely died a few years later, his exact fate shrouded in the grim anonymity of colonial incarceration. His death marked the end of the overt armed struggle, but the spirit of resistance he ignited continued to smolder.

The Pima Revolt had profound consequences for Spanish policy in the Pimería Alta. It highlighted the failures of the existing missionary system and the need for a stronger military presence. The presidios of Tubac and Altar were established or reinforced, increasing the Spanish military footprint. The role of the Jesuits was scrutinized, and their power gradually curtailed. The revolt is often cited by historians as a significant factor contributing to the eventual expulsion of the Jesuits from all Spanish territories in 1767.

For the O’odham people, the revolt was a tragic chapter, yet also a testament to their enduring spirit. While they lost the war, they retained a deep-seated memory of their resistance. The Spanish were forced to acknowledge, if not fully respect, the Pima’s desire for autonomy. Some reforms were implemented, aimed at mitigating the most egregious abuses, though the fundamental power imbalance remained.

The Pima Revolt of 1751 stands as a powerful reminder of the human cost of colonialism and the indomitable will of indigenous peoples to defend their lands, their culture, and their freedom. It was a fire in the desert, briefly illuminating the dark realities of conquest and leaving an indelible mark on the history of the American Southwest. Luis Oacpicagigua, a forgotten hero to many, remains a symbol of defiance, his story a crucial piece in the complex mosaic of North American history, urging us to remember the voices that rose against the tide of empire.