The Forgotten Crucible: Fort Freeland and the Brutal Edge of the American Revolution

The verdant hills of Pennsylvania’s West Branch Susquehanna Valley today whisper of tranquility, a landscape carved by time and the river. Yet, beneath this placid surface lies a history etched in blood and resilience, a testament to the brutal realities of the American Revolution far from the grand battlefields of Saratoga or Yorktown. Here, in the summer of 1779, a small, privately built stockade known as Fort Freeland became a crucible of conflict, its brief, tragic stand a microcosm of the desperate struggle for survival on the American frontier. Its story, often overshadowed by larger narratives, offers a poignant glimpse into the harrowing lives of settlers caught between empires, tribes, and the unforgiving wilderness.

A Frontier on Fire: The Setting

The American Revolution, while fought for ideals of liberty and self-governance, was a deeply complex and often savage affair on the frontier. Pennsylvania, a vast and diverse colony, found its western and northern reaches transformed into a battleground where loyalties were fluid and alliances shifted with the winds of war. The West Branch Susquehanna, a vital artery for trade and settlement, became a flashpoint. Scotch-Irish and German immigrants, seeking new lives and fertile lands, pushed ever westward, encroaching upon territories long held by various Native American nations, primarily the Seneca and Cayuga of the Iroquois Confederacy.

These Native American nations, often feeling betrayed by colonial expansion and seeing their lands threatened, frequently allied with the British. The British, in turn, found willing partners in their strategy to destabilize the rebellious colonies from within, encouraging raids and providing supplies to their Native American allies and Loyalist rangers. This created a volatile mix: American patriots, British regulars, Loyalist Tories, and various Native American groups, all vying for control, often with horrific consequences for the civilian population.

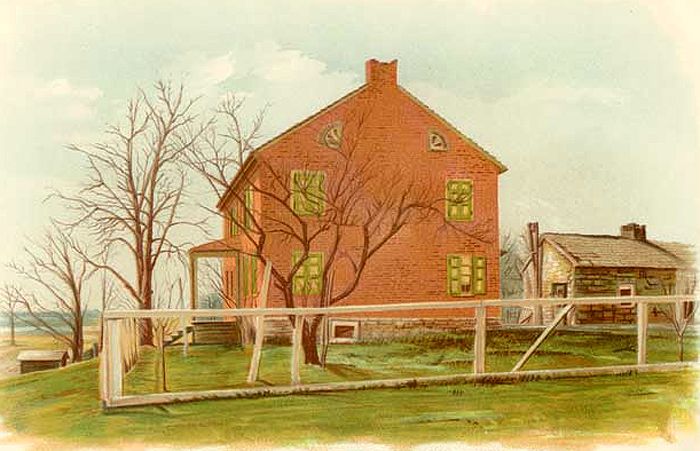

It was into this maelstrom that Jacob Freeland, a prosperous farmer, and his family settled near what is now Watsontown in Northumberland County. Like many frontier families, they understood the need for self-preservation. Around 1775-1776, Freeland, along with his sons and neighbors, constructed a private fort. This was not a grand, government-built edifice with professional garrisons, but rather a stout log stockade, perhaps 100 feet square, enclosing several cabins, a well, and a communal gathering space. It was a testament to sheer settler grit, a defensive island in a sea of untamed wilderness, designed to offer refuge for a handful of families during times of alarm.

The Shadow of Wyoming

The year 1778 had already delivered a devastating blow to frontier morale. Just miles to the east, in the Wyoming Valley, a combined force of British regulars, Butler’s Rangers (Loyalists), and Seneca warriors had utterly crushed American militia forces, resulting in what became known as the Wyoming Valley Massacre. The aftermath was brutal, with widespread slaughter of settlers and the burning of homesteads. This event triggered the "Great Runaway," a panicked exodus of thousands of settlers down the Susquehanna to the relative safety of settlements further south, leaving vast tracts of the frontier deserted.

While some settlers eventually returned, drawn by the promise of their cleared lands and the hope that the worst had passed, the fear lingered. Fort Freeland, like other small outposts such as Fort Muncy and Fort Augusta, became a fragile beacon of hope, a place where families huddled together, their lives dependent on mutual defense and constant vigilance. Yet, the relative calm was deceptive. The British and their allies had not forgotten the Susquehanna.

The Gathering Storm: July 1779

By the summer of 1779, intelligence began to filter through the frontier of another impending attack. Colonel Samuel Hunter, the American commander at Fort Augusta, the primary government outpost in the region, received reports of a large enemy force moving down the river. He dispatched warnings, but the vastness of the territory and the speed of the raiding parties often made effective response difficult.

The attacking force was formidable: an estimated 300 men, a diverse and dangerous coalition led by Captain John MacDonald of the British Army. His command included detachments of Butler’s Rangers – hardened Loyalist frontiersmen intimately familiar with the terrain and the settlers they now considered enemies – and a significant contingent of Seneca and Cayuga warriors, eager to reclaim their ancestral lands and exact retribution. This combined force possessed both the military discipline of the British and the fierce, guerrilla tactics of the Native Americans.

Their target was not just Fort Freeland, but a series of settlements in the fertile valley. The fort, with its strategic location and concentration of families, represented a significant prize.

The Siege and the Surrender

On the morning of July 28, 1779, a day that began like any other, the peace of the valley was shattered. The attackers, moving swiftly and silently under the cover of darkness, surrounded Fort Freeland before dawn. Inside, approximately 20 to 30 armed men, along with women and children, prepared for the worst. The alarm was raised, and the small garrison braced itself.

The siege began with a fierce volley of musket fire and the terrifying war cries of the Native American warriors. The attackers, positioned strategically, poured fire into the log walls. Though the fort’s defenders fought bravely, their numbers were woefully inadequate against such a superior force. The battle raged for hours. The attackers attempted to set the fort ablaze with fire arrows, but the defenders managed to extinguish the flames.

Recognizing the futility of prolonged resistance, and with their ammunition dwindling, the fort’s commander, perhaps Jacob Freeland himself or one of his sons, faced an agonizing decision. Further resistance would only lead to a massacre of everyone inside, including the women and children. A white flag was raised.

Negotiations began. Captain MacDonald, seeking to avoid unnecessary casualties on his own side and perhaps wishing to secure prisoners rather than just dead bodies, offered terms. He guaranteed the lives of all inside, but demanded unconditional surrender and the plundering of the fort. Critically, he stipulated that all men would be taken prisoner, while women and children would be permitted to return to Fort Augusta. It was a harsh bargain, but it offered a slim hope of survival. The defenders, with heavy hearts, accepted.

A Tragic Relief

As the grim process of surrender unfolded, a new, even more tragic chapter began. Unbeknownst to those inside Fort Freeland, a relief party of about 30 American militia, under the command of Captain John Boone (a cousin of Daniel Boone) and Lieutenant Samuel Doyle, was on its way from Fort Augusta. They had heard of the attack and were rushing to aid their besieged comrades.

As they approached the fort, unaware of the surrender, they were ambushed by the main body of MacDonald’s force, which had been concealed in the surrounding woods. It was a devastatingly effective trap. The militia, caught completely by surprise, were cut down in a brutal, one-sided fight. Many were killed outright, including Captain Boone and Lieutenant Doyle. The few survivors were either taken prisoner or managed to escape back to Fort Augusta with harrowing tales of the ambush. This ambush, occurring within sight and sound of the newly surrendered fort, added another layer of despair and horror to the day’s events.

With the fort secured and the relief party annihilated, MacDonald’s men plundered the fort, taking whatever was of value. The stockade and cabins, symbols of settler hope and defiance, were then put to the torch, leaving behind a smoldering ruin.

The Long March and Captivity

The aftermath of Fort Freeland was grim. The women and children, as promised, were allowed to depart for Fort Augusta, though their journey through the wilderness was fraught with danger and grief. The men, however, faced a far more perilous fate. They were marched north, deep into British and Native American territory. Their destination was Fort Niagara, a formidable British stronghold at the confluence of Lake Ontario and the Niagara River, a major hub for operations against the American frontier.

The march was brutal. Prisoners, already weakened by the siege and the shock of capture, were forced to endure long treks, often with inadequate food and water, under the watchful eyes of their captors. Many perished along the way from exhaustion, starvation, or disease. Those who reached Fort Niagara faced the horrors of captivity – overcrowded cells, meager rations, and the constant threat of illness. From Niagara, some were eventually transferred to Montreal, another major British prison center.

For many, captivity lasted for years. Some died in prison, their names lost to history. Others endured until prisoner exchanges could be arranged, returning home as shadows of their former selves, forever scarred by their ordeal. The families left behind lived in agonizing uncertainty, never knowing the fate of their fathers, husbands, and sons.

A Microcosm of Frontier Warfare

The fall of Fort Freeland, though a relatively small engagement in the grand scheme of the American Revolution, was profoundly significant for the Pennsylvania frontier. It underscored the extreme vulnerability of isolated settlements and the terrifying effectiveness of combined British-Loyalist-Native American forces. It also triggered a second "Great Runaway," as remaining settlers, terrified by the fate of Fort Freeland, again abandoned their homes and fled south, leaving the West Branch Valley virtually deserted for a time.

The story of Fort Freeland is a microcosm of the wider frontier war: a conflict marked by sudden, brutal raids, desperate defenses, and immense suffering for civilians. It highlights the complex loyalties and animosities of the time, where neighbors could become enemies and ancient tribal grievances merged with imperial ambitions. It reminds us that the fight for American independence was not just fought by professional soldiers on open fields, but by ordinary families, farmers, and pioneers, defending their homes and their lives against overwhelming odds.

Legacy and Remembrance

Today, little remains of Fort Freeland. The site, located on private land near Watsontown, is marked by a Pennsylvania Historical Marker, a simple bronze plaque that quietly recounts the tragedy. Archaeological digs have been conducted, revealing tantalizing clues about the fort’s layout and the lives of those who sheltered within its walls.

The memory of Fort Freeland, while not as widely known as the Alamo or Gettysburg, endures in local histories and among those dedicated to preserving the often-overlooked stories of the American Revolution. It stands as a powerful reminder of the human cost of war, the courage of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, and the enduring spirit of those who carved a life out of the wilderness. The whispers of the Susquehanna Valley may now be of peace, but for those who listen closely, they still carry the echoes of that fateful July day in 1779, when Fort Freeland became a symbol of a forgotten crucible on the brutal edge of a nascent nation.