The Forgotten Ribbon: Tracing the Legacy of the Ozark Trail Highway

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

In an age of GPS-guided journeys, multi-lane interstates, and predictable rest stops, it’s easy to forget the raw, pioneering spirit that once defined American road travel. Before the federal highway system, before the iconic Route 66, a network of ambitious, often unpaved, roads crisscrossed the nation, born from local ingenuity and a fervent belief in the automobile’s power to connect. Among the most ambitious and enduring of these was the Ozark Trail Highway, a sprawling, grassroots initiative that, for a brief, glorious period, served as a lifeline for communities and a proving ground for the future of American mobility.

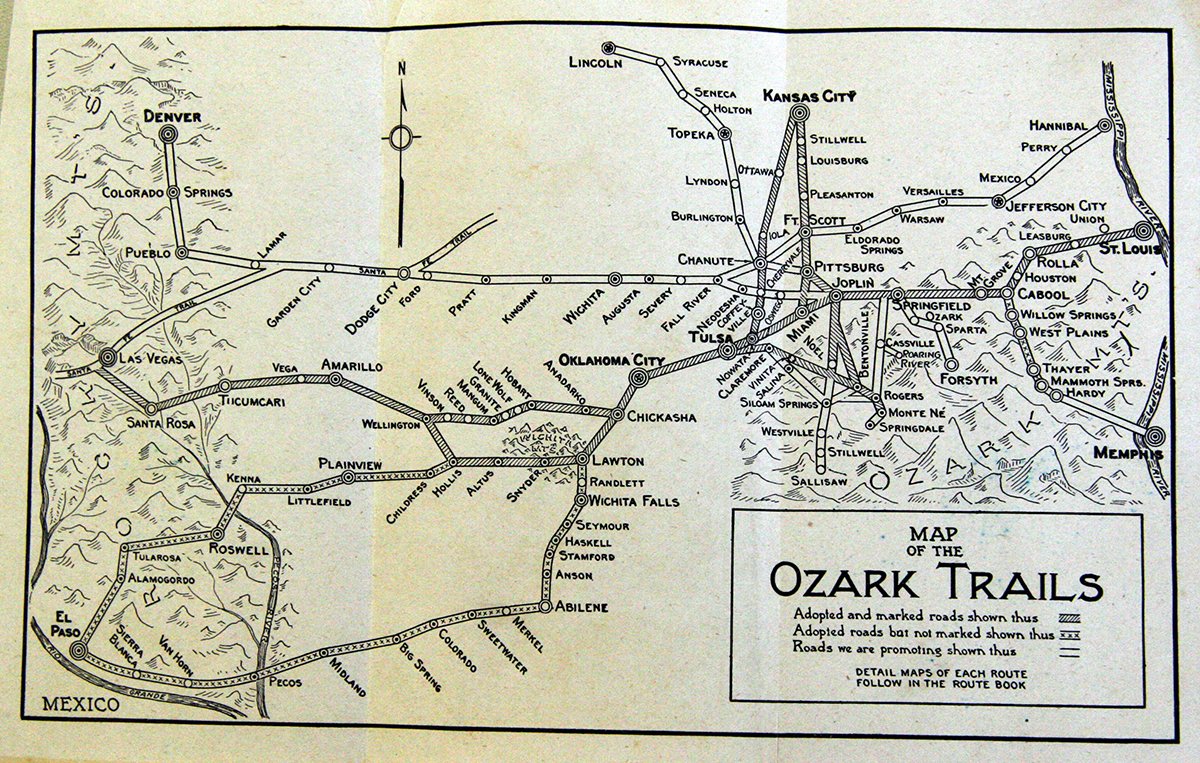

Spanning thousands of miles from the heart of Missouri, through the rugged Ozarks, and stretching all the way to the high plains of New Mexico and even into Texas and Colorado, the Ozark Trail was more than just a path; it was a testament to the collective will of a burgeoning nation. It was a vision brought to life by local boosters, civic leaders, and ordinary citizens who saw beyond the mud and dust, envisioning a future where every town, no matter how remote, could be linked by a dependable ribbon of road.

The Dawn of the Automobile and the "Good Roads" Crusade

The early 20th century was a time of seismic change in America. The horse and buggy were rapidly giving way to Henry Ford’s Model T, and with the proliferation of automobiles came an urgent, undeniable problem: the roads were terrible. Most were little more than dirt tracks, prone to turning into impassable quagmires with the slightest rain or choking dust clouds in dry spells. Long-distance travel was an arduous, often perilous, undertaking.

This pressing need for better infrastructure ignited the "Good Roads Movement." Across the country, local associations, often spearheaded by automobile clubs and chambers of commerce, began to form, advocating for and, in many cases, directly building improved roadways. These early "auto trails" were not built by state or federal governments, which largely remained aloof from road construction until later. Instead, they were products of local pride and enterprise, marked by painted poles, unique logos, and often, the sheer muscle of volunteers.

"The automobile promised freedom, but our roads kept us chained to our immediate surroundings," remarked a contemporary newspaper editorial from Springfield, Missouri, in 1910. "If this nation is to truly move forward, it must build the arteries for its new mechanical heart."

The Visionary: William "Coin" Harvey and the Ozark Trails Association

The spark for the Ozark Trail Highway was ignited in 1913, largely through the efforts of William Hope Harvey, better known as "Coin" Harvey. A colorful and enigmatic figure – a lawyer, author, and ardent proponent of the free silver movement – Harvey had retired to a utopian community he founded in Monte Ne, Arkansas. He quickly recognized the potential of the automobile to transform the region, but also its critical limitation: the lack of decent roads.

Inspired by the successes of other early auto trails like the Lincoln Highway, Harvey convened a meeting in Carthage, Missouri, a central hub in the Ozarks. Here, with a group of like-minded businessmen and civic leaders, the Ozark Trails Association (OTA) was formally established. Their mission was ambitious: to designate, improve, and promote a comprehensive network of roads that would connect the towns and cities of the Ozarks with broader national routes.

"We are not merely building roads," Harvey is often quoted as proclaiming to his fellow boosters, "we are forging pathways to prosperity, linking our communities in a common cause. Every mile we improve brings us closer to a future of boundless opportunity."

The OTA was a true grassroots organization. Membership was open to anyone willing to contribute, and funds were raised through local donations, subscriptions, and even community festivals. Towns vied for the distinction of being on the "Ozark Trail," knowing it would bring travelers, commerce, and prestige.

Mapping the Ribbon: From Missouri to the Southwest

The core of the Ozark Trail originated in Missouri, with key branches emanating from cities like St. Louis, Kansas City, and Springfield. It then snaked its way south and west, through the rugged terrain of the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks, entering Oklahoma near Tulsa, and continuing across the vast expanses of the Texas Panhandle. Its westernmost termini reached into New Mexico, touching Santa Fe and Roswell, and even extending to Pueblo, Colorado, linking up with other auto trails.

Unlike modern highways, the Ozark Trail was not a single, continuous, purpose-built road. Rather, it was a designated route that incorporated existing county roads, farm tracks, and whatever passable paths could be found. The OTA’s primary role was to advocate for improvements, provide directional signage, and publish detailed strip maps for intrepid motorists.

Markers, typically painted poles or rocks emblazoned with the distinctive Ozark Trail logo (often a white circle with a black "OT"), guided travelers. These were vital in an era before widespread road signs, often placed at critical intersections or turns. "You learned to keep an eye out for those white circles," recalled an elderly former motorist in a 1960s interview. "They were your only compass in a landscape that could swallow you whole."

The Journey: An Adventure, Not Just a Trip

Traveling the Ozark Trail in the 1910s and early 1920s was an adventure of epic proportions. Cars were less reliable, and the roads themselves presented formidable challenges. Motorists faced everything from deep ruts and washouts to choking dust in summer and impassable mud in spring and fall. Flat tires were a certainty, often several per journey, and skilled drivers had to be amateur mechanics, carrying spare parts, tools, and even shovels to extricate their vehicles from mire.

Gas stations were rare; fuel was often purchased from general stores or blacksmiths. Lodging was rudimentary, typically in small-town hotels or boarding houses that quickly learned to cater to the new breed of "automobilists." The pace was slow, averaging perhaps 20-25 miles per hour on a good stretch, and far less through rougher terrain. A journey that today takes hours might have taken days or even a week.

Despite the hardships, there was an undeniable romance to the road. It offered a sense of freedom, discovery, and camaraderie among fellow travelers. Local communities, eager for the economic boost, often welcomed motorists with open arms, providing assistance, directions, and a taste of regional hospitality. "Every town felt like a triumph, every successful crossing of a muddy creek a victory," wrote a correspondent for Motor Age magazine in 1917, describing a trip along the Ozark Trail. "It was less a journey and more an expedition into the heart of America."

Economic and Cultural Impact

The Ozark Trail Highway played a crucial role in the economic and social development of the regions it traversed. It brought previously isolated communities into closer contact, facilitating trade and commerce. Farmers could more easily transport their goods to market, and businesses in small towns saw an influx of customers. The nascent tourism industry also received a significant boost, as more people could explore the scenic beauty of the Ozarks and beyond.

The trail also fostered a sense of regional identity and cooperation. Towns that were once rivals found common cause in improving the road that linked them. It was a tangible symbol of progress and modernity, transforming the landscape and the mindset of the people who lived along its path.

The Sunset of the Auto Trails and a Lasting Legacy

The golden age of the independent auto trails, including the Ozark Trail Highway, began to wane in the mid-1920s. With the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, the U.S. government became more deeply involved in road construction, and by 1926, the familiar numbered U.S. Route system was implemented.

This new system, with its federal funding and standardized signage, effectively absorbed many of the routes established by the auto trail associations. Sections of the Ozark Trail became parts of iconic U.S. Highways like US-66, US-71, US-60, and others, their local names fading from common use. The Ozark Trails Association, having achieved its initial goals and seeing its mission taken over by government agencies, eventually disbanded.

Today, the physical remnants of the original Ozark Trail Highway are largely obscured. Some stretches have been paved and incorporated into modern highways, while others have reverted to gravel roads, farm tracks, or have simply been abandoned to nature. There are no grand monuments, no national parks dedicated solely to its memory.

Yet, its legacy endures. The Ozark Trail Highway, and others like it, laid the foundational groundwork for the vast, interconnected highway system we rely on today. It demonstrated the power of community organization, the economic necessity of good roads, and the transformative potential of the automobile. It was a vital, if largely forgotten, chapter in the story of American mobility – a testament to the pioneering spirit that, nearly a century ago, literally paved the way for the nation’s journey forward. The forgotten ribbon of the Ozark Trail, though faded from view, continues to whisper tales of adventure, ambition, and the enduring human desire to connect.