The Gallows and the Ghost of Reason: The Tragic Fate of Reverend George Burroughs

On a sweltering August day in 1692, the air on Gallows Hill in Salem Town was thick with a morbid anticipation. A crowd had gathered, a swirling mass of fear, fanaticism, and morbid curiosity, to witness yet another chapter in the unfolding horror of the Salem Witch Trials. But among the condemned that day, one figure stood out, an anomaly that should have shattered the very foundations of the proceedings: the Reverend George Burroughs.

Burroughs, a Harvard-educated minister, was not a marginalized outcast, a cranky old woman, or a social deviant. He was a man of God, a respected intellectual, and a former spiritual leader in the very community that was now sending him to his death. His execution, arguably the most shocking and unsettling of all, served as a chilling testament to the unchecked hysteria that had gripped colonial Massachusetts, a stark reminder of how quickly reason can capitulate to terror.

Born around 1650, George Burroughs was a product of a burgeoning New England. He graduated from Harvard College in 1670, a prestigious accomplishment that marked him as a man of intellect and standing in a society that revered education, particularly for its clergy. His early career, however, was marked by a restlessness and a series of challenging postings, often on the rugged frontier of Maine, then known as the District of Maine.

His first significant charge was in Salem Village (now Danvers) in 1680. It was a brief, tumultuous tenure, lasting only three years. Salem Village was a contentious place, a parish riddled with internal strife and factionalism, a precursor to the divisions that would explode a decade later. Burroughs found himself caught in the crossfire. More critically, he found himself embroiled in a bitter financial dispute with the powerful Putnam family and with his successor, the notoriously litigious Samuel Parris. Burroughs claimed the community owed him salary, while Parris accused him of unpaid debts related to his first wife’s funeral. This simmering resentment, a debt unpaid and a grudge harbored, would prove to be a fatal thread in the tapestry of his life.

Leaving Salem Village in 1683, Burroughs sought refuge and new opportunities on the perilous Maine frontier, serving communities in Wells and Falmouth (present-day Portland). Life there was harsh. He ministered amidst the constant threat of Native American attacks, often leading his congregation in defense against raids. He was known for his physical strength and his ability to endure the hardships of frontier life, attributes that would ironically be twisted into damning evidence against him. Yet, even in Maine, financial woes and interpersonal conflicts continued to plague him, further cementing a reputation for being somewhat troubled, if not outright problematic, in the eyes of some.

As the winter of 1692 gave way to spring, the nascent witch hysteria in Salem Village began its terrifying ascent. What started with the afflictions of Parris’s daughter, Betty, and niece, Abigail Williams, quickly spiraled into a contagion of accusations. The spectral finger of the afflicted girls, initially pointing at social outcasts like Tituba, Sarah Good, and Bridget Bishop, soon began to reach for more prominent members of the community.

It was in April 1692 that the whispers concerning Reverend Burroughs began. The afflicted girls, including Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, and Elizabeth Hubbard, started to claim that a spectral minister, a "black minister," was tormenting them. He was accused of bewitching soldiers, causing the deaths of his former wives, and even shape-shifting. The historical animosity between Burroughs and the Parris/Putnam faction, fueled by the unresolved financial disputes, provided a ready-made motive for the accusations. Mercy Lewis, who had once been a servant in Burroughs’s household in Maine, played a particularly significant role, claiming she was terrorized by his specter and that he often visited her at night, pressing her with the covenant of the Devil.

On May 4, 1692, a warrant was issued for Burroughs’s arrest. He was seized from his home in Wells, Maine, and brought back to Salem, a journey of over 70 miles, under armed guard. The very act of his arrest, a respected minister being dragged from his pulpit, sent shockwaves through the region, yet it did little to quell the rising tide of fear.

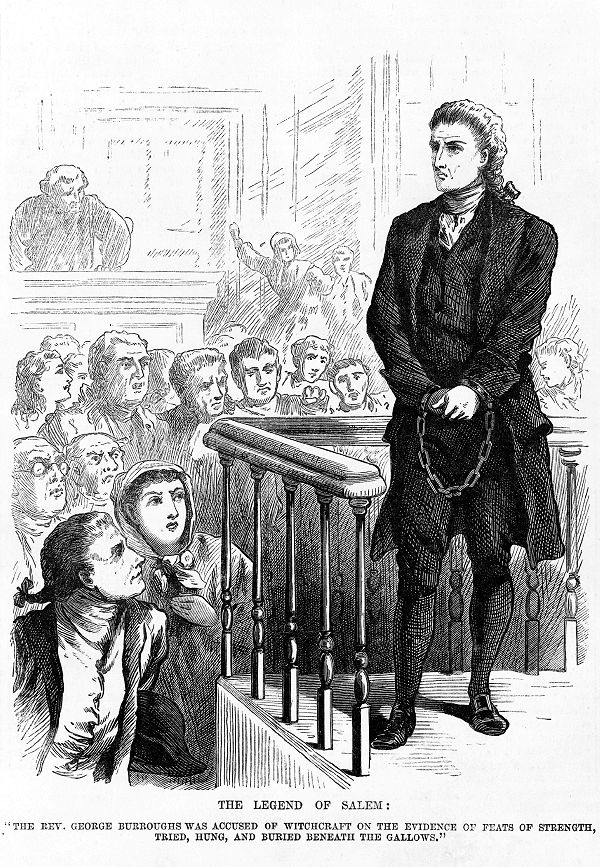

His examination and subsequent trial before the Court of Oyer and Terminer were a masterclass in judicial perversion. The evidence presented against him was almost entirely spectral, the testimony of the "afflicted" who claimed to see his specter tormenting them, to feel his invisible hand pinching and choking them. When Burroughs merely looked at the girls in the courtroom, they would fall into fits, writhe on the floor, and cry out in pain, claiming his evil gaze was afflicting them. This was taken as irrefutable proof of his guilt.

Among the most damning – and bizarre – pieces of "evidence" was testimony regarding Burroughs’s extraordinary physical strength. Witnesses claimed he could lift a heavy fowling piece, a musket, by inserting just one finger into the barrel. This feat, rather than being dismissed as an exaggeration or a testament to his frontier hardiness, was interpreted by the court as undeniable proof of diabolical assistance, a clear sign that the Devil imbued him with unnatural power. Cotton Mather, a prominent minister who later defended the trials, would record this accusation, noting that Burroughs "was a very puny man; yet he had often done things beyond the strength of a giant."

Burroughs vehemently denied all charges, asserting his innocence and appealing to the common sense that seemed to have abandoned the court. He maintained that he believed in witchcraft, but not that he was a practitioner. He questioned the nature of spectral evidence, arguing that the Devil could appear in the form of an innocent person, a theological point that was gaining traction among some skeptical ministers but was largely ignored by the fervent court.

His defense was eloquent, his pleas earnest, but they were utterly ineffectual against the overwhelming weight of spectral testimony and the court’s unyielding belief in the accusers. His own daughter, in a desperate attempt to save her father, was coerced into making a false confession of witchcraft, a confession she later recanted, but by then it was too late. The court, swept up in a tide of credulity, found him guilty.

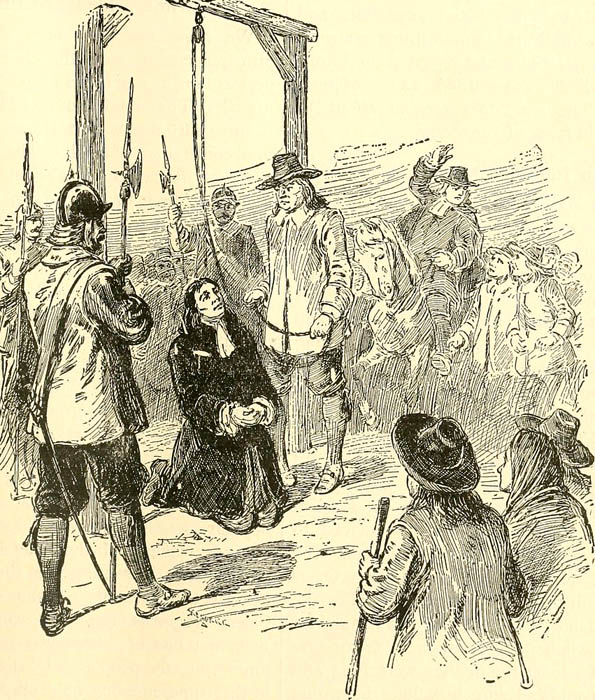

On August 19, 1692, George Burroughs was led to Gallows Hill alongside four other condemned individuals: John Willard, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., and John Proctor. As he stood on the ladder, a noose around his neck, he performed an act that, under normal circumstances, would have granted him an immediate reprieve. He recited the Lord’s Prayer perfectly, without a single error or hesitation.

According to the prevailing Puritan belief of the time, witches and those in league with the Devil were incapable of reciting the Lord’s Prayer without stumbling or making a mistake. Burroughs’s flawless recitation sent a ripple of doubt through the assembled crowd. Many were deeply moved, murmuring that surely, a man of God, capable of such a prayer, could not be a witch. Some even began to cry out for his release.

It was at this critical moment that Reverend Cotton Mather, a towering figure in the Puritan establishment and a staunch supporter of the trials, intervened. Mounted on his horse, Mather addressed the wavering crowd, his voice cutting through the rising tide of doubt. He reminded them that Burroughs was not an "ordained" minister (a subtle jab at his tumultuous career and financial disputes) and, more importantly, he argued that "the Devil has often been transformed into an Angel of Light." Mather asserted that Burroughs’s ability to recite the prayer was merely another trick of Satan, a cunning deception to mislead the righteous.

Mather’s words were powerful, his authority immense. The momentary surge of compassion and reason dissipated, replaced once more by fear and conviction. The crowd quieted, their doubts quelled by the minister’s pronouncement. With the last glimmer of hope extinguished, Reverend George Burroughs was hanged until dead. In a final act of indignity, his body, like those of the other accused, was not allowed a proper burial. It was instead cast into a shallow, unmarked grave near the gallows, a grim testament to the utter dehumanization wrought by the trials.

The execution of George Burroughs marked a turning point, or at least a moment of profound reflection, for many. If a Harvard-educated minister, a man of God, could be condemned on such flimsy, spectral evidence, who among them was truly safe? The absurdity of his charges, coupled with his dignified final moments, chipped away at the collective certainty that fueled the trials. Within months, the tide began to turn, with growing skepticism among prominent figures leading to the eventual collapse of the Court of Oyer and Terminer and the end of the witch hunt.

Reverend George Burroughs’s tragic fate serves as a chilling emblem of the Salem Witch Trials’ most profound injustices. He was a victim of personal grudges, community paranoia, and a legal system that prioritized spectral accusation over due process and rational thought. His story underscores the dangers of mass hysteria, the abuse of authority, and the devastating consequences when fear triumphs over reason. In the quiet cemeteries and historical markers of Salem, his ghost, the ghost of reason silenced, continues to whisper a timeless warning to us all.