The Ghost Fortress of Santa Rosa: A Tale of Ambition, Isolation, and Vanished Dreams

On the windswept, mist-shrouded shores of Santa Rosa Island, one of California’s remote Channel Islands, a powerful silence reigns. Today, the island is a sanctuary of raw natural beauty, home to unique flora and fauna, and a protected wilderness within Channel Islands National Park. Yet, beneath the scrub and sand, and etched into the collective memory of the island’s original inhabitants, lies the spectral outline of a forgotten dream: Presidio Isla Santa Rosa. A short-lived Spanish military outpost, its very existence speaks volumes about the grand, often futile, ambitions of empire, the resilience of indigenous peoples, and the unforgiving power of nature.

To understand the brief, poignant life of Presidio Isla Santa Rosa, we must first cast our gaze back to the late 18th century. Spain, a sprawling global power, was nervously eyeing its vast, sparsely settled territories in Alta California. Rumors of Russian fur traders pushing south from Alaska and British explorers probing the Pacific Northwest coast sent shivers down the spine of Spanish colonial authorities. The vast expanse of California, though nominally Spanish, was largely unprotected. To solidify its claim and provide a defensive chain, Spain embarked on a mission to establish presidios (military forts) and missions along the coast, stretching from San Diego to San Francisco.

The Chumash Homelands: A World Before Contact

Before any European sail pierced the horizon, Santa Rosa Island, known to its people as Wima, had been home to the Island Chumash for thousands of years. These were sophisticated maritime people, renowned for their intricate plank canoes (tomols), their deep understanding of the rich marine environment, and a vibrant culture that thrived on trade with mainland communities. Their settlements dotted the island, testament to a harmonious, if sometimes challenging, relationship with their island home. The Channel Islands were not merely isolated landmasses; they were an integral part of a vast, interconnected Chumash world, a watery highway traversed by skilled mariners.

"The Chumash had a deep spiritual and practical connection to these islands," explains Dr. Mona L. Johnson, an ethnohistorian specializing in California’s indigenous peoples. "Their society was complex, with intricate social structures, advanced technologies for resource management, and a rich oral tradition. The arrival of the Spanish was not an act of discovery, but an invasion that shattered a long-established way of life."

The Imperial Gaze Turns West

It was into this ancient world that Spanish ambition intruded. By the late 1780s, the chain of presidios on the mainland was taking shape: San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey, and San Francisco. But the Channel Islands, particularly the larger ones like Santa Rosa, presented both a strategic opportunity and a logistical nightmare. The idea of an island presidio was audacious, a forward defensive position intended to monitor shipping lanes and, crucially, to control the large and relatively independent Chumash population of the islands.

The impetus for establishing a fort on Santa Rosa Island specifically gained traction around 1788. Governor Pedro Fages of Alta California, ever vigilant against foreign encroachment, saw the island as a potential base for enemies and a place where "pagan" natives might evade the civilizing influence of the missions. His vision was to bring the island Chumash into the fold, both spiritually and as a labor force, and to secure the strategic Santa Barbara Channel.

The Dream Takes Shape: A Garrison Against the Elements

The chosen site for Presidio Isla Santa Rosa was likely a sheltered cove, offering some protection from the relentless Pacific winds and waves, but still exposed to the raw power of the elements. Sometime between 1788 and 1790, a small detachment of Spanish soldiers, perhaps no more than a dozen or two, along with a handful of Native American auxiliaries and possibly a missionary or two, landed on Santa Rosa. Their task was formidable: to construct a fort from scratch, establish a presence, and survive.

Life for these soldiers was unimaginably harsh. The island offered little in the way of immediate resources. Fresh water was scarce and often brackish, requiring arduous treks to distant springs or the collection of rainwater. Building materials were limited; they would have relied on local stone, timber washed ashore, and whatever meager supplies could be ferried across the treacherous channel from the mainland presidio at Santa Barbara.

"Imagine the isolation," says David M. Brown, a park ranger at Channel Islands National Park with a passion for its history. "These were men far from home, cut off from regular communication, facing the constant roar of the ocean and the stark reality of a desolate landscape. Their sense of purpose must have been tested daily."

Their daily routines would have involved endless chores: constructing defensive walls, digging latrines, searching for food, maintaining their meager weapons, and constantly scanning the horizon for signs of unwelcome ships – or the more immediate threat of a storm. Disease, scurvy, and malnutrition would have been constant companions. For the native auxiliaries, the experience was likely even more brutal, forced into labor and alienated from their ancestral ways.

Interaction with the Island Chumash: A Complex and Coercive Dance

The presence of the Spanish soldiers fundamentally altered the lives of the Island Chumash. While the soldiers’ primary mission was defensive, their interaction with the native population was critical. The Spanish needed the Chumash for labor, knowledge of local resources, and as a potential source of converts. For the Chumash, the Spanish represented a new, powerful, and often terrifying force.

Historians suggest that the Spanish attempted to exert control over the islanders, encouraging (or coercing) them to move closer to the presidio, to adopt Spanish customs, and eventually to relocate to the mainland missions. The Chumash, however, were not easily subjugated. Their intimate knowledge of the island, their mobility in their tomols, and their strong social structures allowed many to resist direct Spanish authority for a time.

However, the most devastating impact of the Spanish presence was unintentional: disease. European diseases, to which the Chumash had no immunity, swept through the islands with catastrophic speed. Smallpox, measles, and influenza decimated populations, weakening communities and making them more vulnerable to Spanish influence and forced removal. The population of the Channel Islands plummeted dramatically in the decades following European contact.

A Swift Demise: Nature’s Victory

Despite the grand intentions, the Presidio Isla Santa Rosa was doomed to be a fleeting enterprise. The logistical challenges proved insurmountable. Supplying the small garrison across the turbulent Santa Barbara Channel was a constant struggle. Ships were often delayed or unable to make the crossing due to weather, leaving the soldiers perilously low on food, water, and other necessities. The cost of maintaining such a remote outpost, with so little tangible return, was also a major factor.

By 1790 or 1791, barely a year or two after its establishment, the Spanish authorities recognized the futility of the venture. The meager resources of Alta California simply couldn’t sustain such an isolated and difficult post. The soldiers were withdrawn, the structures likely dismantled for their reusable materials, or simply abandoned to the elements. The wind, rain, and relentless erosion quickly reclaimed the site. Within a few short years, little physical trace remained of Spain’s ambitious island fortress.

The Ghost in the Sand: Archaeology Unearths a Past

For centuries, Presidio Isla Santa Rosa existed only as a footnote in historical records, a whispered memory among the descendants of the Chumash, and perhaps a few scattered fragments in the sand. It wasn’t until the advent of modern archaeology that the "ghost fortress" began to yield its secrets.

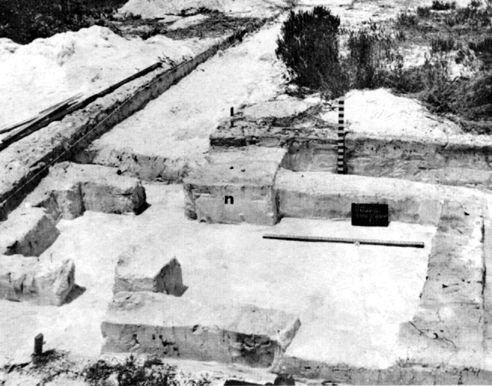

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, archaeological teams, often in collaboration with the National Park Service and the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, have systematically explored parts of Santa Rosa Island. Their painstaking work has slowly begun to uncover the faint outlines of the presidio. While no grand stone structures remain standing, archaeologists have found tell-tale signs of the Spanish presence.

"Locating a site like Presidio Isla Santa Rosa is like finding a needle in a very large, wild haystack," explains Dr. Margaret Sanchez, an archaeologist who has worked on the Channel Islands. "We’re not looking for towering walls, but subtle changes in soil, concentrations of specific artifacts, and faint indications of human activity that are centuries old. Every shard of pottery, every rusty nail, tells a story."

Excavations have unearthed fragments of majolica pottery, olive jar shards, musket balls, iron tools, and remnants of European-style ceramics – all unmistakable evidence of Spanish occupation. These artifacts, though small, paint a vivid picture of daily life: what they ate, what they cooked in, what they wore, and what they used for defense. The location of these finds, combined with historical maps and geological surveys, has helped pinpoint the probable site of the presidio.

One particularly poignant find might be a fragment of a rosary or a religious medallion, speaking to the spiritual life these isolated men attempted to maintain. Another could be the remains of a European-introduced animal, like a pig or a goat, which would have been brought over as a food source, further altering the island’s ecosystem.

A Lingering Legacy: Lessons from the Island

Today, Presidio Isla Santa Rosa is not a physical monument, but a powerful historical echo. It serves as a multi-layered lesson:

- The Folly of Overreach: It underscores the limits of imperial power when confronted by immense logistical challenges and the raw force of nature. Spain’s ambition was grand, but its resources and practical capabilities were often strained to their breaking point.

- The Impact of Contact: The presidio, however short-lived, was a vector of profound change for the Island Chumash. It symbolized the beginning of a period of immense suffering, displacement, and cultural upheaval, even as it also sparked resistance and resilience. The story of the Chumash, their survival, and their ongoing efforts to reclaim their heritage is an integral part of the presidio’s narrative.

- The Power of Archaeology: The almost complete disappearance of the physical structure highlights the crucial role of archaeology in recovering lost histories. Without the meticulous work of excavators, the story of Presidio Isla Santa Rosa might have remained forever shrouded in the mists of time.

- The Enduring Spirit of Place: Santa Rosa Island itself, having weathered millennia of human presence and absence, remains a testament to the enduring power of wilderness. It silently witnessed the Chumash thrive, the Spanish struggle, and then reclaimed its solitude, leaving only faint whispers of the human drama that unfolded upon its shores.

As visitors gaze out from Santa Rosa Island today, across the vast, blue expanse of the Pacific, they are not just seeing a beautiful landscape. They are standing on ground steeped in history, where the dreams of empire clashed with the realities of the wild, and where the ancient rhythms of an indigenous people were irrevocably altered. The ghost fortress of Santa Rosa is a powerful reminder that even the most ambitious human endeavors can be ephemeral, yet their stories, once unearthed, continue to resonate, offering profound insights into our shared past.