The Ghost in the Fluted Point: Unearthing the Folsom Culture

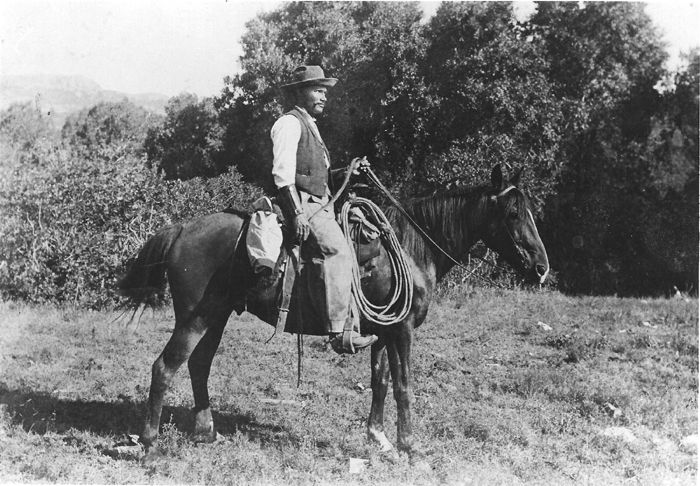

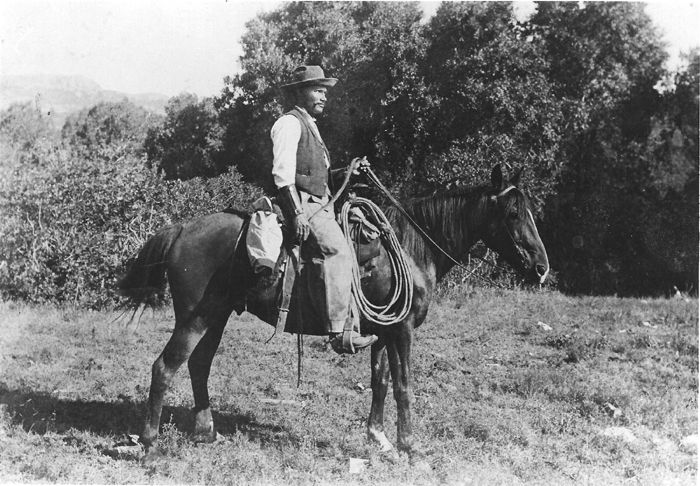

The year was 1926. In the sun-baked arroyos of New Mexico, a cowboy named George McJunkin was pursuing a lost calf near the town of Folsom when he stumbled upon a sight that would shatter long-held scientific beliefs about the peopling of the Americas. Strewn across a deeply eroded gully were the massive bones of an extinct form of bison, Bison antiquus, larger and more formidable than any modern species. More astonishingly, nestled between the ribs of one of these ancient beasts was a finely crafted stone spear point, a testament to an encounter between man and megafauna that scientists had, until then, deemed impossible for such an early age.

This unassuming discovery at Folsom, New Mexico, irrevocably pushed back the timeline of human presence in North America by millennia. It ushered in the recognition of what we now call the Folsom culture, a highly specialized group of Paleoindian hunter-gatherers who roamed the vast, ice-age grasslands of North America between approximately 12,800 and 12,000 years ago. Their story, etched in stone and bone, is one of incredible adaptability, technological prowess, and an intimate understanding of a world now vanished.

A Spear Point That Changed History

Before McJunkin’s find, the prevailing scientific consensus, largely influenced by the "antiquity of man" debates, suggested that humans had only arrived in North America a few thousand years ago. The discovery of human artifacts alongside megafauna in undisturbed geological context was the critical piece of evidence needed to challenge this paradigm. When the Denver Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science) dispatched archaeologists to the site, they meticulously excavated the area. On August 27, 1927, an excavating archaeologist, Frank Figgins, called for the attention of visiting scientists: a stone projectile point was clearly visible, in situ, still embedded within the matrix of the ribs of a Bison antiquus. This was the irrefutable proof the scientific community demanded.

The Folsom point itself is an archaeological marvel. Typically thin, lanceolate (leaf-shaped), and exquisitely crafted, its most distinctive feature is the "flute" – a long, shallow channel removed from both faces of the point, extending from the base towards the tip. This fluting served a practical purpose: it allowed the point to be hafted more deeply and securely into a wooden spear shaft, creating a more robust and lethal weapon. The manufacturing process for these points required exceptional skill, involving precise pressure flaking and careful preparation of the stone core. It’s estimated that a significant percentage of attempts to create a perfect Folsom point likely resulted in breakage, underscoring the value of each successful artifact and the expertise of its maker.

As Dr. David Meltzer, a prominent archaeologist specializing in Paleoindian cultures, notes, "The Folsom point represents a highly sophisticated lithic technology, a clear marker of a people who were not just surviving, but thriving through ingenuity in a challenging environment." This technological signature became the defining characteristic of the Folsom culture, allowing archaeologists to trace their movements and activities across the continent.

Masters of the Bison Hunt

The Folsom people were, above all, specialized bison hunters. Their primary prey was Bison antiquus, a formidable animal standing up to eight feet tall at the shoulder and weighing over 2,000 pounds, significantly larger than modern bison. Hunting such a beast with stone-tipped spears required immense courage, coordination, and an intimate knowledge of animal behavior and the landscape.

Folsom kill sites, found predominantly across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountain foothills, reveal a sophisticated approach to hunting. These sites often contain the remains of dozens, sometimes hundreds, of bison, indicating large-scale communal hunts. Strategies likely included driving herds into natural traps such as arroyos, box canyons, or over cliffs. Once cornered, the hunters would move in, dispatching the animals with their fluted spear points.

"The Folsom people weren’t just opportunistic hunters; they were strategic and highly organized," explains Dr. Vance Haynes, another leading expert on Paleoindian archaeology. "Their kill sites show a clear pattern of targeted, large-scale procurement, suggesting a complex social structure capable of coordinating many individuals for a common goal."

Beyond the initial kill, the Folsom people were incredibly efficient in their utilization of resources. Every part of the bison was valuable: meat for sustenance, hides for clothing and shelter, bones for tools and fuel, sinews for cordage, and even dung for fires. This comprehensive use speaks to a deep respect for their prey and a practical understanding of survival in a world with few readily available resources. Their nomadic lifestyle was intrinsically linked to the movements of the bison herds, following them across the vast grasslands in an annual cycle of hunting and gathering.

The Folsom World: An Ice Age Tapestry

The world of the Folsom people was vastly different from today’s. They lived during the final throes of the Last Glacial Maximum, an epoch often referred to as the Ice Age. While the massive Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets covered much of northern North America, the unglaciated regions to the south experienced a cooler, wetter climate than today, supporting immense grasslands and vast boreal forests. This environment was a true "megafauna paradise."

Alongside Bison antiquus, the Folsom people shared their landscape with other now-extinct giants: mammoths, mastodons (though Folsom sites rarely feature mammoths as primary prey, unlike earlier Clovis sites), camels, horses, and saber-toothed cats. While these other species were present, the Folsom cultural signature is overwhelmingly tied to the bison. Their geographic distribution stretched from Alberta, Canada, south to Texas and into the eastern United States, with a concentration in the American West and Great Plains – the prime habitat for their favored prey.

This was a world of stark beauty and brutal challenges. Temperatures were colder, and seasons were more pronounced. Survival depended on keen observational skills, the ability to read the land and its creatures, and the strength of communal bonds. The Folsom culture stands as a testament to humanity’s remarkable capacity to adapt and thrive in extreme conditions, harnessing their intelligence and tool-making skills to master their environment.

Folsom and Clovis: A Complex Relationship

The discovery of the Folsom culture came after the initial recognition of the older Clovis culture, characterized by larger, earlier fluted points. Clovis sites generally date from around 13,400 to 12,800 years ago, making them chronologically ancestral to Folsom. This temporal overlap and shared fluting technology have led to extensive debate among archaeologists about the precise relationship between the two.

Was Folsom a direct descendant of Clovis, a regional adaptation that refined the fluting technology to specialize in bison hunting? Or was it a distinct cultural innovation that emerged in parallel or shortly after Clovis, perhaps influenced by different environmental pressures? While the exact lineage remains a subject of ongoing research, the general consensus is that Folsom likely represents a specialized, refined evolution of the fluted point tradition, perhaps arising from a regional Clovis population that increasingly focused on bison as other megafauna declined.

The transition from Clovis to Folsom also coincides with significant environmental shifts and the rapid disappearance of many megafauna species, an event known as the Younger Dryas climatic reversal. This period saw a sudden return to near-glacial conditions, dramatically impacting ecosystems. The Folsom people, with their hyper-specialization in bison hunting, demonstrate a remarkable ability to adapt to these changing conditions, even as their world was undergoing profound transformation.

The Vanishing World and Folsom’s Legacy

The Folsom culture eventually faded, giving way to later Paleoindian traditions known as the Plano cultures, characterized by long, unfluted lanceolate points (e.g., Eden, Scottsbluff, Agate Basin). This transition, occurring around 12,000 years ago, corresponds with the end of the Younger Dryas, the warming climate, and the final extinction of Bison antiquus and other megafauna. As the Ice Age truly receded, the landscape changed, and the animals Folsom hunters relied upon vanished.

The legacy of the Folsom culture, however, endures. It stands as a pivotal chapter in the human story of North America, illustrating the profound ingenuity and resilience of early inhabitants. Their discovery provided undeniable proof of deep human antiquity on the continent, opening the door for further archaeological exploration and understanding.

Today, archaeologists continue to study Folsom sites, employing advanced techniques like DNA analysis on ancient bison bones, precise radiocarbon dating, and detailed lithic analysis to piece together more nuanced details of their lives. Each new find adds to our understanding of their social structures, their mobility patterns, and their incredible ability to adapt to a challenging, dynamic environment.

The Folsom culture, though long silent, speaks to us across the millennia through the elegant precision of its fluted points and the silent testimony of its kill sites. It reminds us of a time when humanity, armed with little more than stone and skill, confronted and mastered a world teeming with giants, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape and in the annals of human history. Their story is a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of human innovation and survival, echoing from the ancient grasslands into our modern understanding of our deepest past.