The Ghost of Milk Creek: A Colorado Legend of Blood and Betrayal

America’s tapestry of legends is woven with threads of grand narratives – pioneering spirit, manifest destiny, and the relentless push westward. Yet, beneath the epic tales often lie quieter, more tragic sagas, less celebrated but profoundly impactful, shaping the very ground we stand on. One such legend, etched into the rugged landscape of northwestern Colorado, is the Battle of Milk Creek, a brutal clash in 1879 that sealed the fate of the Ute people and stands as a stark reminder of the often-bloody cost of expansion. It is a story of cultural misunderstanding, broken promises, and the desperate fight for ancestral lands, echoing a sorrowful refrain throughout the nation’s history.

To understand Milk Creek, one must first appreciate the Ute Nation, the "Blue Sky People," who had roamed the vast, pristine wilderness of what is now Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico for centuries. Their lives were intimately connected to the land, guided by seasonal migrations, hunting, and a deep spiritual reverence for nature. But by the mid-19th century, their world was shrinking. The Pikes Peak Gold Rush of 1859 brought a deluge of white settlers, prospectors, and homesteaders, all eyeing the rich resources of Ute territory. Treaties, ostensibly designed to protect Ute lands, were repeatedly negotiated, broken, and renegotiated, each iteration pushing the Utes onto smaller, less desirable reservations. The 1868 treaty, for instance, established a large reservation in western Colorado, but even this was coveted by land-hungry settlers and politicians.

Enter Nathan Meeker, an idealistic but profoundly misguided Indian Agent appointed to the White River Ute Agency in 1878. Meeker, a former newspaper editor and founder of the utopian Union Colony (now Greeley, Colorado), harbored a fervent belief in "civilizing" the Utes. His vision was to transform them from nomadic hunters into sedentary farmers, cutting their long hair, sending their children to school, and forcing them to adopt Anglo-American ways. He saw their traditional lifestyle as "savagery" and believed his mission was to uplift them, whether they wanted it or not.

Meeker’s approach was, at best, culturally insensitive; at worst, aggressively coercive. He famously plowed up a Ute horse racing track, a site of significant cultural importance, to plant crops, declaring, "This is not an Indian reservation; it is an American farm." He cut rations for those who resisted his reforms and frequently threatened to call in the military. The Utes, led by figures like Chief Jack (Nicaagat) and Chief Colorow, grew increasingly resentful. They valued their horses, their hunting grounds, and their traditions. They saw Meeker’s demands as an assault on their very identity and a clear violation of their treaty rights. The tension at the agency became a powder keg.

Meeker, feeling increasingly isolated and threatened by the Utes’ resistance, repeatedly telegraphed Washington D.C., pleading for military assistance. He painted a picture of rebellious, dangerous Indians on the verge of uprising, though many historians now argue his fear was largely a product of his own inflexibility and inability to understand Ute culture. On September 10, 1879, Meeker’s urgent pleas were answered. Major Thomas T. Thornburgh, commander of Fort Steele in Wyoming, was ordered to march his troops to the White River Agency, ostensibly to restore order and protect Meeker.

Thornburgh, a seasoned officer, departed with a force of some 175 men, including three companies of cavalry (Co. E and F of the 5th Cavalry, and Co. D of the 3rd Cavalry) and one company of infantry (Co. E of the 4th Infantry), along with a wagon train carrying supplies. As they neared the reservation, Chief Jack sent messengers to Thornburgh, requesting that he stop his advance and come to the agency with only a small escort to discuss the situation. The Utes viewed the presence of such a large military force as a direct act of aggression, a precursor to conflict, not a peace-keeping mission. Thornburgh, perhaps wary of an ambush, or simply following orders to proceed, refused the request, stating he would continue to within a day’s march of the agency before parleying. This decision, however understandable from a military perspective, cemented the Utes’ belief that the troops intended hostile action.

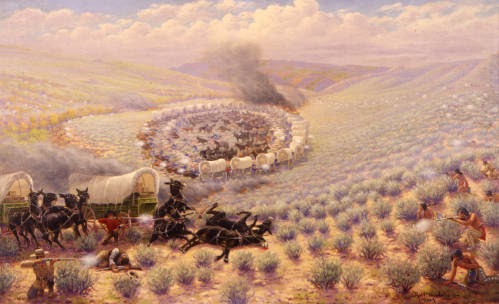

On September 29, 1879, Major Thornburgh’s column was making its way through a narrow, brush-choked canyon along Milk Creek, about 18 miles north of the agency. The Utes, knowing the terrain intimately, had chosen their ground well. They had dug rifle pits on the high bluffs overlooking the creek and concealed themselves in the dense sagebrush and timber. As the vanguard of Thornburgh’s column entered the trap, the Utes opened fire. The surprise was complete and devastating.

"The crack of a thousand rifles seemed to burst upon us at once," later recounted Private Fred S. Brown of the 5th Cavalry. The first volleys decimated the leading elements of the column. Major Thornburgh, at the head of his troops, was among the first to fall, shot through the head. His death threw the command into chaos. Captain J. Scott Payne quickly took charge, ordering the troops to fall back to the supply wagons. Under intense fire, the soldiers frantically began to construct a defensive perimeter. They overturned wagons, dug rifle pits with their bayonets and bare hands, and piled up goods to form makeshift barricades. It was a desperate struggle for survival.

The Ute warriors, numbering perhaps 200 to 300, maintained a relentless siege. They were expert marksmen and masters of guerrilla warfare, using the terrain to their advantage. For days, the soldiers were pinned down, suffering from thirst, hunger, and the constant barrage of Ute bullets. Horses, the lifeblood of the cavalry, became prime targets, their bodies providing grim additional cover for the besieged troops. Water was a critical issue; the creek, tantalizingly close, was heavily guarded by Ute sharpshooters. Attempts to reach it often ended in death.

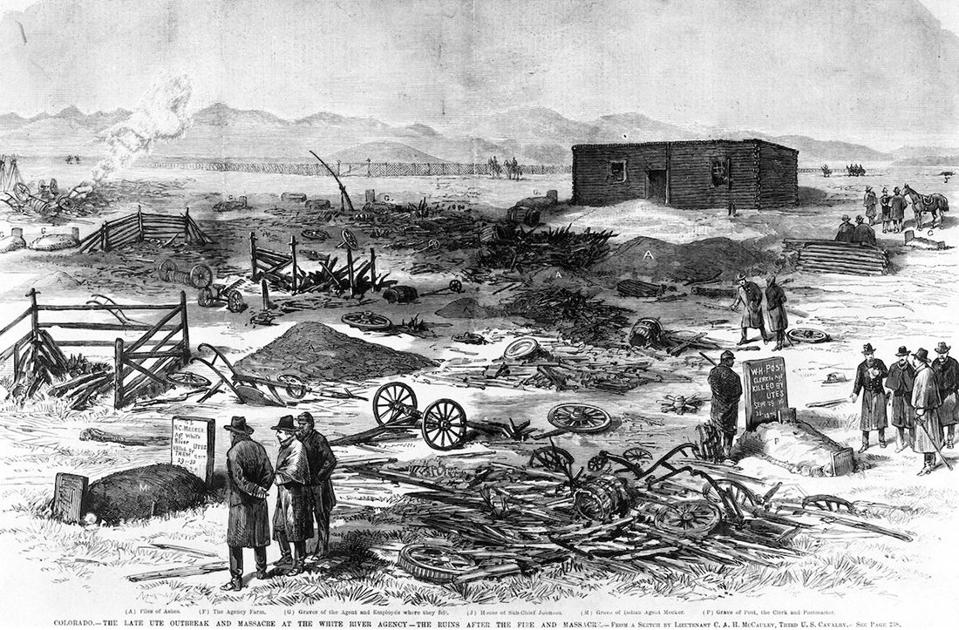

While the battle raged at Milk Creek, a separate, equally horrific tragedy unfolded at the White River Agency. On the very same day, September 29, the Utes, enraged by the military invasion and perhaps believing Meeker had deliberately provoked the conflict, stormed the agency. Nathan Meeker and ten of his male employees were killed, their bodies mutilated. Meeker himself was found with a stake driven through his mouth, a gruesome symbol of his inability to listen. Meeker’s wife, Arvilla, his daughter, Josephine, and two other women and children were taken captive by the Utes. This "Meeker Massacre," as it became known, fueled public outrage and intensified demands for retribution.

Back at Milk Creek, the situation was dire. Captain Payne, wounded but resolute, sent out couriers under the cover of darkness, risking their lives to seek reinforcements. One scout, Rankin, managed to slip through the Ute lines and ride over 160 miles in just 28 hours to reach Fort Steele with news of the disaster. General Wesley Merritt, commanding the Department of the Platte, immediately mobilized a relief column of several hundred cavalry and infantry, including elements of the 5th Cavalry and 9th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers). Merritt’s force embarked on a forced march, covering ground at an incredible pace.

On October 2, after nearly five days of siege, the Ute warriors, realizing a much larger military force was approaching, began to withdraw. The sound of Merritt’s cavalry trumpets in the distance signaled their arrival. Merritt’s troops found a scene of devastation: 13 soldiers, including Major Thornburgh, were dead, and 48 others wounded. Nearly all the horses were killed. The men were exhausted, parched, and traumatized. The Milk Creek engagement was a decisive Ute victory in military terms, but its long-term consequences would be catastrophic for them.

The news of the Milk Creek Battle and the Meeker Massacre ignited a firestorm across Colorado and the nation. Newspapers screamed headlines demanding vengeance. The cry "The Utes Must Go!" became a rallying cry for politicians and citizens alike. This public outcry, fueled by fear, racism, and the insatiable desire for Ute lands, quickly translated into political action. Despite the fact that the Utes had only acted in self-defense against an invading army, and despite the heroic efforts of Chief Ouray (a respected Ute leader who had not been involved in the fighting) to negotiate the release of the captive women, the outcome was predetermined.

In 1880, Congress passed the Ute Removal Act. The White River Utes, the Northern Utes, were forcibly relocated from their ancestral lands in Colorado to a small reservation in eastern Utah. The Southern Utes were also moved to a much smaller reservation in southwestern Colorado. The vast, resource-rich lands of western Colorado, once the domain of the Utes, were opened up to white settlement and exploitation. It was a tragic end to an ancient way of life, a stark example of how military conflict, often provoked by misunderstandings and land greed, could lead to the decimation of indigenous populations.

The legend of Milk Creek is not one of glorious victory, but of bitter lessons. It speaks to the devastating consequences of cultural insensitivity, the broken promises of treaties, and the relentless march of "progress" at any cost. It is a legend whispered by the winds through the Milk Creek canyon, where the ghosts of soldiers and Ute warriors still contend for meaning. It reminds us that America’s past is complex, often contradictory, and that understanding these lesser-known, painful chapters is crucial to truly grasping the rich, diverse, and sometimes sorrowful tapestry of our shared history. The legacy of Milk Creek lives on, not just in the dusty annals of history, but in the enduring spirit of the Ute people and in the continuing dialogue about land, sovereignty, and justice in America.