The Ghosts in the Pristine Wilderness: Vermejo Ranch’s Coal Town Legacy

Today, Vermejo Park Ranch in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado is synonymous with unparalleled natural beauty, sprawling conservation efforts, and exclusive outdoor pursuits. Spanning over 550,000 acres, it is Ted Turner’s largest property, a meticulously managed haven for elk, bison, and trout, where luxury lodges cater to a select few seeking respite in a pristine wilderness. Yet, beneath the serene surface and verdant landscapes lies a buried history, a stark contrast to its present tranquility. Vermejo was once a bustling, grimy, and dangerous industrial powerhouse, home to a network of coal towns that fueled the American West. These vanished communities, particularly the infamous Dawson, represent a vital, often overlooked, chapter in the ranch’s story, echoing with the whispers of thousands who toiled and died in the pursuit of black gold.

The genesis of Vermejo’s coal empire can be traced back to the vast Maxwell Land Grant, a Mexican land grant of immense proportions that eventually encompassed much of what would become the ranch. While the grant’s early history was marked by cattle ranching and timber, the true wealth lay hidden beneath the earth: colossal seams of high-quality bituminous coal. As the American industrial revolution gained momentum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the demand for coal to power railroads, smelters, and nascent industries skyrocketed. Companies like Phelps Dodge and the Colorado Fuel & Iron (CF&I) Company recognized the immense potential, acquiring mineral rights and establishing mining operations that would transform the remote landscape.

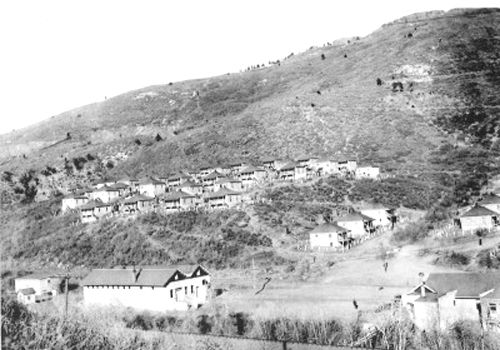

The coal towns that sprang up across the Vermejo landscape were quintessential company towns, born of necessity and controlled by the corporations that owned them. From the moment a miner arrived, nearly every aspect of his life, and that of his family, was dictated by the company. Housing, often basic and uniform, was rented from the company. Food, clothing, and supplies were purchased at the company store, frequently at inflated prices, with wages often paid in company script – currency redeemable only within the company’s domain. This system created a cycle of dependence, making it difficult for workers to save money or seek alternatives, effectively binding them to their employer.

Among these towns, Dawson stood as the undisputed capital of the Vermejo coal empire. Established in 1901 by the Dawson Fuel Company, later acquired by Phelps Dodge, it quickly grew into one of New Mexico’s largest and most significant coal mining operations. At its peak, Dawson boasted a population of over 9,000, a vibrant, multi-ethnic tapestry woven from immigrants drawn by the promise of work from Italy, Greece, Slavic countries, Mexico, and other parts of the United States. It was a self-sufficient town, featuring not just mines and coke ovens, but also a hospital, schools, churches, a hotel, an opera house, a bank, and even its own professional baseball team. The sheer scale of Dawson was staggering; it produced millions of tons of coal annually, transforming raw material into the energy that drove the burgeoning industries of the Southwest.

Life in Dawson, and other Vermejo coal towns like Van Houten, Brilliant, Gardiner, and Swastika, was a complex blend of hardship and community. The work itself was brutally dangerous. Miners toiled in dark, cramped, and dusty conditions, constantly facing the threats of cave-ins, explosions, and the slow, insidious onset of "black lung" disease. "My grandfather always said the coal dust was so thick sometimes, you could barely see your hand in front of your face, even with a lamp," recounts a fictional descendant, echoing countless real-life testimonies. "But he also spoke of the camaraderie, the way the men looked out for each other, no matter where they came from."

This camaraderie was essential in an environment where tragedy was a constant specter. Dawson, in particular, suffered two catastrophic mine explosions that etched its name into the annals of American industrial disasters. The first, on October 22, 1913, claimed the lives of 263 men and boys, many of them recent immigrants. A secondary explosion, triggered by rescue efforts, killed another miner. The town was plunged into mourning, and the sheer number of victims overwhelmed its small cemetery, leading to the creation of a vast, silent field of identical white crosses that still stands today. Just a decade later, on February 8, 1923, disaster struck again when an explosion killed 120 miners. These two events, separated by just ten years, underscored the immense human cost of the nation’s energy demands, leaving deep scars on the community and its survivors.

Despite the ever-present danger, these towns fostered a unique social fabric. Each ethnic group brought its own traditions, languages, and culinary practices, creating a vibrant, if sometimes tense, cultural mosaic. Holidays were celebrated with gusto, community dances were frequent, and sports, especially baseball, provided a much-needed outlet and a source of local pride. The company, while exerting immense control, also provided certain amenities that might not have been available in such remote areas, from rudimentary healthcare to educational facilities. However, this paternalism was always shadowed by the underlying exploitation, as profits consistently outweighed worker welfare.

The decline of the Vermejo coal towns was as swift and dramatic as their rise. Several factors converged to bring about their demise. Economically, the nation began shifting its energy focus away from coal towards oil and natural gas, especially after World War II. Demand for high-sulfur coal, common in the region, waned. Simultaneously, increasing mechanization in mining reduced the need for a large manual workforce, making many operations redundant. The devastating mine disasters also played a role, not just in the loss of life, but in the growing public and regulatory pressure on mine safety, which added to operational costs.

Phelps Dodge made the decision to cease operations in Dawson in 1950. The closure was abrupt and final. The company offered workers the opportunity to relocate to other mines or to purchase their homes for a nominal fee, provided they moved them off company land. Many chose to leave, often dismantling their houses to be reassembled elsewhere, or simply abandoning them. The company then systematically razed the remaining structures, eager to erase the industrial footprint and reclaim the land. Within a few years, a thriving town of thousands had virtually disappeared, leaving behind only the concrete foundations of buildings, scattered artifacts, and, most poignantly, the silent rows of white crosses in the cemetery.

The closure of Dawson marked the end of an era for the entire Vermejo property. The land, stripped of its industrial purpose, entered a new phase of ownership and vision. Phelps Dodge eventually sold the vast acreage, and after passing through several hands, it was acquired by Ted Turner in 1996. Turner, a passionate conservationist, envisioned Vermejo not as a resource to be extracted, but as a living landscape to be restored and protected. Under his stewardship, the focus shifted entirely from industry to ecology.

Today, the transformation is almost complete. Nature has reclaimed much of the land where bustling towns once stood. Forests have grown over former mine entrances, and grasslands now cover areas once blackened by coal dust. Yet, for those who know where to look, the ghosts of the coal towns remain. Faint outlines of roads, the occasional brick chimney, discarded mining equipment, and the tell-tale flat areas that once held buildings are subtle reminders of the human drama that unfolded here. The most tangible and powerful remnant is the Dawson Cemetery, a solemn testament to the hundreds who perished in the mines. Its meticulously maintained white crosses, bearing names like Di Paolo, Rodriguez, Kruzich, and Suzuki, silently narrate the multicultural story of a community built on grit and sacrifice.

The legacy of Vermejo’s coal towns offers a profound counterpoint to the ranch’s modern identity. It is a story of America’s relentless drive for industrialization, fueled by the labor of immigrants and the vast resources of the land. It speaks to the boom-and-bust cycles that defined many Western towns, and the often-harsh realities of life in company-controlled environments. It also highlights the incredible resilience of both the human spirit and the natural world.

From a landscape scarred by mines and coke ovens, Vermejo has emerged as a beacon of conservation. The wealth extracted from its depths, though often at great human cost, ultimately contributed to the economic forces that shaped the nation. Now, the land itself, once a source of fuel, is a sanctuary for wildlife and a testament to the power of environmental stewardship. The ghosts of Dawson and its sister towns are not just historical footnotes; they are integral to the identity of Vermejo Ranch, a poignant reminder that even the most pristine wildernesses often hold complex and challenging human histories, whispering tales of struggle, community, and ultimate transformation.