The Gold and The Ghost: Reclaiming Kate Carmack, Matriarch of the Klondike

The name "Klondike Gold Rush" conjures images of rugged prospectors, icy rivers, and the instant fortunes that built legends. It’s a tale often told through the lens of daring white men who braved the unforgiving Yukon wilderness, striking it rich against impossible odds. Yet, at the very heart of this epic, a pivotal figure has long been relegated to the shadows: Kate Carmack, a Tagish woman whose knowledge, resilience, and very presence were indispensable to the monumental discovery that sparked one of history’s greatest stampedes. Her story is not merely a footnote; it is a foundational chapter, a testament to Indigenous resilience, knowledge, and the enduring power of a woman who, despite everything, shaped history.

Born Shaaw Tláa around 1871, Kate belonged to a prominent Tagish family with strong ties to the Tlingit people of the coastal regions. Her family, including her brothers Keish (Skookum Jim Mason) and Káa Goox (Tagish Charlie), were renowned hunters, trappers, and guides, possessing an intimate, ancestral knowledge of the vast, intricate network of rivers, mountains, and game trails that crisscrossed the Yukon and Alaska. This was not merely survival; it was a sophisticated understanding of an entire ecosystem, passed down through generations – a knowledge that would prove invaluable, and ultimately, be exploited.

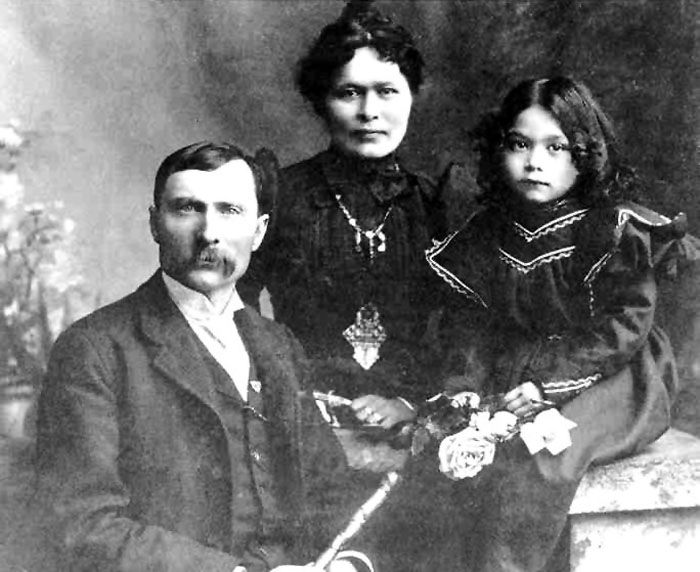

Kate’s life took an unexpected turn when she met George Carmack, an American prospector and adventurer who had immersed himself in Indigenous ways of life, learning their languages and adopting their customs. He was, in the parlance of the time, a "squaw man" – a derogatory term, but one that highlighted his willingness to bridge cultural divides, at least initially. In 1887, Kate and George were married in a traditional Tagish ceremony, a union that blended two worlds. For George, Kate and her family represented not just companionship, but an unparalleled connection to the land and its resources, an essential asset in the harsh, untamed frontier. For Kate, it offered a glimpse into a changing world, though one that would ultimately prove treacherous.

Together with her brothers, Kate and George formed a tight-knit prospecting and trapping team. They were a formidable unit, navigating the rugged terrain with a blend of Western prospecting techniques and traditional Indigenous wisdom. Kate was no passive observer; she was an active participant, contributing her exceptional skills in hunting, fishing, and camp management, as well as her unparalleled understanding of the environment. Her ability to identify edible plants, track game, and navigate the treacherous waterways was critical to their survival and success.

The fateful day arrived on August 17, 1896. The team, including Kate, George, Skookum Jim, and Tagish Charlie, were camped on Rabbit Creek (later renamed Bonanza Creek) after a successful salmon fishing expedition. The standard narrative, propagated by George Carmack, claims he "discovered" the gold, often depicted as him idly scratching the ground and finding a nugget. However, the Indigenous account, and increasingly, the consensus among historians, paints a very different picture.

According to Skookum Jim and Tagish Charlie, it was Jim who first made the significant find. While George was napping or cleaning up, Jim, known for his keen eye and extensive knowledge of the land, spotted coarse gold in a creek bed. He excitedly called the others over. George, upon seeing the gold, immediately understood its implications and wasted no time in staking a claim, famously writing "I, George Carmack, do hereby locate and claim by right of discovery, 1,500 feet on this creek."

Kate’s role in this moment, though often downplayed or omitted entirely from early histories, was undeniable. She was present, an active member of the team, her expertise in the land and resources having brought them to that very spot. Her family’s knowledge of the region’s geology, particularly the tell-tale signs of mineral deposits often associated with riverbeds and ancient glacial activity, would have been implicitly or explicitly part of the collective wisdom they brought to bear. She was not just a companion; she was an equal partner in a prospecting team that relied heavily on traditional Indigenous survival skills and an understanding of the terrain. As historian James A. Michener once observed, "The history of the West is not just about the men who explored it, but the women, particularly the Native women, who guided and sustained them."

The discovery on Rabbit Creek ignited the Klondike Gold Rush. News spread like wildfire, and within months, tens of thousands of hopeful prospectors descended upon the remote Yukon, transforming it from a wilderness into a bustling, chaotic frontier. The Carmack team, now wealthy beyond imagination, became instant celebrities. George, Skookum Jim, and Tagish Charlie were celebrated as the "discoverers," their names etched into the annals of gold rush lore.

Initially, Kate shared in the newfound wealth and notoriety. George took her to San Francisco, a world away from the Yukon wilderness. For a brief period, she lived a life of luxury, wearing fashionable clothes, attending social events, and experiencing urban life. However, this transition was fraught with challenges. Kate, a Tagish woman, faced pervasive racism and cultural alienation in the predominantly white society. She was often viewed as a curiosity, an exotic "squaw" from the wilds, rather than an intelligent, capable woman who had played a crucial role in one of history’s most significant discoveries. George, increasingly influenced by societal pressures and the allure of a "respectable" white wife, began to distance himself from his Indigenous roots and, cruelly, from Kate.

The ultimate betrayal came in 1900. George Carmack, having amassed a fortune, abandoned Kate. He sought a divorce, but in the eyes of the burgeoning white legal system, their traditional Tagish marriage held no official standing. Kate, in effect, had no legal claim to the wealth they had collectively earned. George married another woman, Marguerite Laimee, and conveniently erased Kate from his narrative, leaving her with a meager settlement, a fraction of what she deserved.

Heartbroken and dispossessed, Kate returned to the Yukon. She attempted to secure her rightful share of the fortune, but the legal and societal barriers were insurmountable. The system was rigged against Indigenous women, denying them agency, property rights, and recognition. Despite her personal struggles, Kate remained a respected figure within her community. She continued to live off the land, demonstrating the resilience and deep connection to her ancestral heritage that defined her. She died in 1920 in a small cabin in Tagish, Yukon, in relative obscurity and poverty, a stark contrast to the immense wealth her estranged husband continued to enjoy.

Kate Carmack’s story is a powerful indictment of the historical erasure of Indigenous women’s contributions and the systemic injustices they faced. For decades, her name was largely absent from textbooks and popular accounts of the Klondike Gold Rush, relegated to a footnote or simply omitted. The narrative prioritized the white male prospector, perpetuating a myth of individual triumph that conveniently overlooked the crucial role played by Indigenous knowledge, guidance, and partnership.

However, in recent years, a concerted effort by Indigenous communities, historians, and academics has begun to reclaim Kate Carmack’s rightful place in history. Her story is being retold, not as a passive figure, but as an active agent, a skilled survivor, and a co-discoverer. The re-evaluation highlights several crucial aspects:

- Indigenous Knowledge as Foundation: Kate and her family’s profound understanding of the land was not incidental; it was the bedrock upon which the gold discovery was made possible. Without their expertise in navigating, surviving, and identifying resources in the Yukon, George Carmack’s prospecting efforts would likely have been futile.

- Challenging the "Discovery" Myth: The narrative that George Carmack "discovered" the gold single-handedly is being dismantled, replaced by a more accurate account that acknowledges the collective effort, and particularly Skookum Jim’s role, with Kate as an integral part of that team.

- Symbol of Injustice: Kate’s abandonment and subsequent poverty serve as a poignant symbol of the systemic racism and legal disenfranchisement faced by Indigenous women in the colonial era. Her experience highlights the fragility of Indigenous rights and the ease with which their contributions could be dismissed and their lives devalued.

- Resilience and Reclamation: Despite the hardships, Kate returned to her people and her land, embodying the enduring spirit of Indigenous resilience. Her story today is a powerful tool in reconciliation efforts, forcing a critical re-examination of historical narratives and advocating for greater recognition of Indigenous peoples’ contributions to Canadian and global history.

Today, monuments, educational materials, and historical interpretations are slowly beginning to reflect Kate Carmack’s true significance. Her name, Shaaw Tláa, is being restored, and her narrative is emerging from the shadows. She is no longer just "George Carmack’s wife," but a historical figure in her own right – a matriarch of the Klondike, whose legacy reminds us that history is often more complex, more collaborative, and far more diverse than the simplified tales we are sometimes told. Reclaiming Kate Carmack’s story is not just about correcting a historical record; it is about acknowledging the profound contributions of Indigenous women and ensuring that their voices, once silenced, are finally heard and celebrated. Her ghost no longer haunts the margins of history; she now stands at its heart, a beacon of truth and a testament to the enduring spirit of the Klondike.