The Grand Riviera: A Fading Echo of Detroit’s Gilded Age

In the annals of Detroit’s architectural and cultural history, few names resonate with as much bittersweet nostalgia as the Grand Riviera Theatre. Once a beacon of opulence and a vibrant hub of entertainment, its story is a poignant microcosm of the Motor City itself: a narrative of breathtaking ambition, dazzling success, gradual decline, and ultimately, a tragic disappearance. Today, where its majestic façade once stood, there is only an empty lot, a silent testament to a grandeur that has been irrevocably lost, leaving behind only photographs, fading memories, and the echo of applause in the city’s collective consciousness.

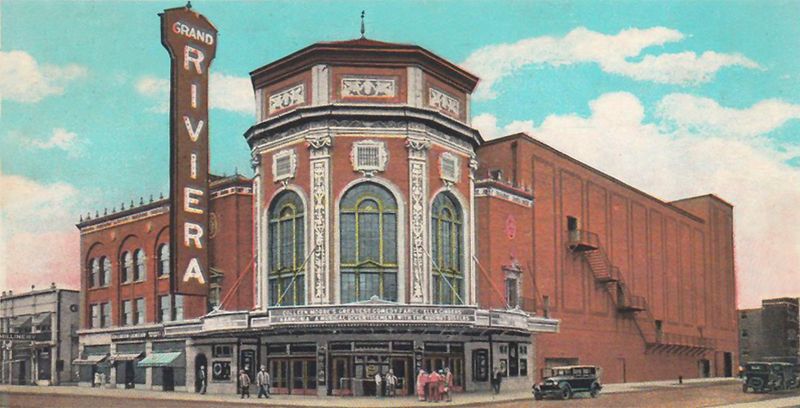

Opened on September 19, 1925, the Grand Riviera was not merely a cinema; it was an experience, a portal to another world. Designed by the legendary architect John Eberson, a master of the "atmospheric" theatre style, the Riviera was a fantastical creation. Eberson’s philosophy was to transport patrons from the mundane reality of the city streets into an exotic, dreamlike setting. He famously stated his goal was to "bring the outdoors indoors," and at the Grand Riviera, he achieved this with breathtaking artistry.

Stepping through its doors at 9222 Grand River Avenue, patrons were immediately enveloped in a simulated Mediterranean courtyard under a starlit sky. The ceiling was painted a deep indigo, studded with twinkling lights that mimicked constellations, while a projector cast moving clouds across its expanse. Walls were adorned with intricate Spanish and Moorish architectural details, including faux balconies, archways, and statuary, all bathed in soft, romantic lighting. Lush tropical plants, trickling fountains, and even singing birds (real or simulated) completed the illusion, creating an unparalleled sense of escapism. With seating for over 3,000 people, the Grand Riviera was not just a venue; it was a destination, a grand palace of dreams where the ordinary ceased to exist for a few precious hours.

The theatre’s opening was met with widespread acclaim. It was an era when movie palaces were the cathedrals of popular culture, and the Riviera quickly established itself as one of Detroit’s most prestigious. Initially, it showcased first-run silent films, accompanied by a magnificent Wurlitzer organ, alongside live vaudeville acts. Audiences flocked to witness the latest cinematic marvels and be entertained by the era’s biggest stars, all within an environment that was itself a spectacle. The Grand Riviera was a cornerstone of Detroit’s booming entertainment scene, drawing families, couples, and friends from across the city and beyond, eager for a taste of its magic.

As the decades unfolded, the Grand Riviera adapted to the changing tides of entertainment. With the advent of sound films, the theatre seamlessly transitioned, continuing to draw massive crowds. By the 1950s and 60s, as vaudeville faded, the Riviera became a premier venue for live music concerts. Its spacious stage and impressive acoustics made it a favorite stop for touring national acts and a vital platform for local talent. This was Detroit’s golden age of music, and the Grand Riviera played a crucial role in it. Legends like Marvin Gaye, The Supremes, The Temptations, Aretha Franklin, James Brown, and many other Motown and R&B giants graced its stage. It was a place where audiences could witness the birth of new sounds and experience the raw energy of live performance, cementing its status as a cultural landmark.

"The Riviera was more than just a building; it was where Detroit came alive," recalled Eleanor Vance, a lifelong Detroit resident in an archival interview. "You dressed up to go there. It was glamorous. You saw the biggest stars, and you felt like you were part of something truly special. The air was always buzzing with excitement."

However, the grandeur of the Grand Riviera, like much of Detroit, began to face insurmountable challenges in the latter half of the 20th century. Socio-economic shifts, including suburbanization, the rise of television, and changing entertainment habits, gradually eroded the profitability of grand downtown movie palaces. Detroit itself was undergoing profound transformations, marked by industrial decline, white flight, and the devastating urban unrest of 1967. These factors took a heavy toll on the city’s once-thriving entertainment districts.

The Grand Riviera, once a symbol of opulence, slowly began to show its age. Maintenance became sporadic, and the elaborate atmospheric details, once meticulously cared for, started to deteriorate. Ownership changed hands multiple times, each new proprietor struggling to find a viable path forward for the aging behemoth. In the 1970s and 80s, the theatre saw a brief resurgence as a venue for rock concerts and community events, but these efforts were often temporary fixes, unable to reverse the deeper currents of decline. The theatre that had once hosted thousands of joyful patrons began to feel increasingly desolate, its once-vibrant magic dimmed by neglect and economic hardship.

By the late 1980s, the Grand Riviera stood as a stark monument to a bygone era, its former glory largely eclipsed by decay. The once-gleaming façade was stained, its intricate details crumbling. The interior, once a marvel of illusion, was now scarred by water damage, peeling paint, and the pervasive smell of disuse. Despite its historical significance, the cost of restoration was astronomical, far exceeding the resources of any potential preservationists in a city grappling with its own profound financial struggles.

The final, devastating blow came on the night of November 17, 1989. A massive fire erupted within the theatre, quickly engulfing the structure. Firefighters battled the blaze for hours, but the inferno proved too powerful. The roof collapsed, and much of the interior, including the beloved atmospheric elements, was completely destroyed. The fire was not merely an accident; it was a tragic, symbolic end, a final, fiery curtain call for a theatre that had already been slowly dying.

The charred remains of the Grand Riviera stood for nearly two more years, a grim reminder of what had been lost. Despite pleas from preservationists and nostalgic citizens, the structure was deemed too far gone, too dangerous, and too costly to salvage. In 1991, the wrecking ball moved in, systematically dismantling what was left of the once-proud edifice. The Grand Riviera Theatre, a masterpiece of architectural imagination and a cornerstone of Detroit’s cultural identity, was reduced to rubble, leaving behind only a barren plot of land.

The demolition of the Grand Riviera was a significant loss, not just for Detroit but for architectural history. John Eberson’s atmospheric theatres were unique, and the Riviera was considered one of his finest examples. Its disappearance represented the eradication of a tangible link to a vibrant past, a physical space where generations of Detroiters had shared moments of joy, wonder, and collective experience. It joined a growing list of Detroit’s lost architectural treasures, each demolition leaving an irreplaceable void in the city’s urban fabric and collective memory.

Today, the site where the Grand Riviera Theatre once stood remains largely undeveloped, an open wound on the landscape of Grand River Avenue. Occasionally, discussions arise about potential new developments, but nothing has materialized to truly fill the void left by Eberson’s masterpiece. The space is a stark reminder of the impermanence of even the grandest structures and the challenges faced by cities in preserving their heritage amidst economic and social upheaval.

Yet, the spirit of the Grand Riviera persists. It lives on in the stories of those who remember its starlit ceiling and the roar of the crowd. It exists in the archival photographs that capture its breathtaking beauty and the programs that list the legendary artists who graced its stage. It is a symbol of Detroit’s resilient spirit, a city that, despite its losses, continues to dream and rebuild.

The Grand Riviera Theatre’s story is a powerful lesson in the importance of architectural preservation and cultural memory. It reminds us that buildings are more than just bricks and mortar; they are vessels of history, repositories of shared experiences, and anchors of community identity. While the Grand Riviera may be gone, its legacy endures – a shimmering, bittersweet echo of Detroit’s gilded age, forever etched in the heart of a city that cherishes its past even as it bravely forges its future. Its absence serves as a poignant warning, urging us to protect the remaining fragments of our architectural heritage before they too fade into the silence of history.