The Great Exodus: When Hope Bloomed on the Kansas Prairie

In the late 1870s, as the promise of Reconstruction faded into the grim reality of Jim Crow, a remarkable migration began in the American South. Tens of thousands of African Americans, newly freed but increasingly re-enslaved by economic bondage and terror, looked westward to a distant horizon – Kansas. It was a land they envisioned not merely as a destination, but as a latter-day Promised Land, a haven where they could finally plant roots of true freedom. This monumental movement, driven by desperation and an unyielding faith, would come to be known as the Kansas Exodus, and its participants, the "Exodusters," etched an indelible chapter in American history.

The post-Civil War South was a cauldron of unfulfilled promises and escalating violence for African Americans. The brief glimmer of hope brought by federal protection and the right to vote quickly extinguished as Reconstruction ended in 1877. With the withdrawal of federal troops, white supremacy reasserted itself with brutal efficiency. Black Codes, designed to restrict the movement and economic independence of former slaves, morphed into Jim Crow laws. Sharecropping and tenant farming, often enforced with predatory contracts and the threat of violence, trapped generations in a cycle of debt and poverty, eerily reminiscent of slavery. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups unleashed a reign of terror, lynching and intimidating Black communities to suppress their political and economic aspirations.

It was against this backdrop of despair that the idea of an exodus took root. The dream of "forty acres and a mule," promised but largely undelivered, had soured. Land, the ultimate symbol of independence and wealth, remained largely out of reach. For many, staying in the South meant perpetual subjugation. "There was no way out of the South," recalled one former slave, "unless you had a white man’s protection, and that was no protection at all."

The seeds of the Kansas Exodus were sown by charismatic figures like Benjamin "Pap" Singleton, a former slave from Tennessee. Singleton, deeply frustrated by the lack of opportunities and the systemic oppression in the South, began actively promoting migration to Kansas. He had earlier attempted to establish Black colonies within Tennessee but faced resistance and economic hardship. By the late 1870s, his message shifted: "The white people of the South have got no use for the colored man, and they are going to drive him out." He saw Kansas, a state with a fervent abolitionist past and a reputation as John Brown’s battleground for freedom, as the ideal destination.

Singleton and other promoters, like Henry Adams of Louisiana, spread the word through circulars, handbills, and passionate speeches. They painted vivid pictures of Kansas as a land of fertile soil, cheap land, and most importantly, unbridled freedom. The message resonated deeply with a people steeped in biblical narratives; the comparison to the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt to the Promised Land was not lost on them. Kansas became their Canaan, a place where they could truly own land, vote without fear, educate their children, and live with dignity.

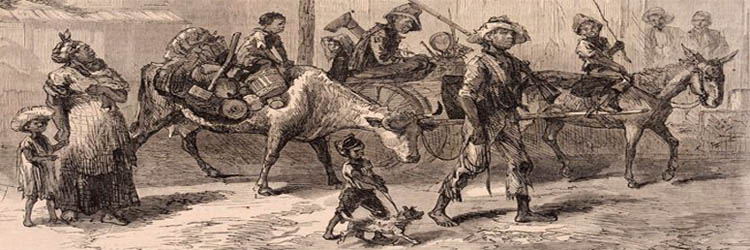

The peak of the exodus occurred in 1879. Thousands upon thousands, sometimes entire families or even whole communities, packed what few belongings they possessed – often just the clothes on their backs, a cooking pot, and a worn Bible – and began the arduous journey. They traveled by foot, by wagon, and most notably, by steamboat up the Mississippi River. The journey itself was a testament to their faith and desperation. Many arrived at river ports in St. Louis or Kansas City destitute, starving, and exhausted. Reports from the time describe scenes of overwhelming poverty, but also of an unshakeable resolve. One observer noted the "exodusters were without money, without food, without clothing, without shelter, and often without hope, but they were determined to stay."

The sheer scale of the migration overwhelmed existing infrastructure and challenged the perceptions of many. Estimates suggest that between 40,000 and 60,000 African Americans left the South for Kansas in this period. Their arrival often sparked a mixed reaction from white Kansans. While some, particularly those with abolitionist sympathies, offered aid and support, others viewed the influx with suspicion, concern, or outright hostility, fearing economic competition or a shift in the state’s racial demographics.

Upon arriving in Kansas, the dream often collided with a harsh reality. The promised land was not paved with gold. Many Exodusters arrived with no money, no tools, and no immediate prospects for work or land. They found themselves camped in makeshift shelters, dependent on the charity of others. Fortunately, aid organizations like the Kansas Freedmen’s Relief Association, led by Governor John P. St. John and figures like Elizabeth Comstock, a Quaker philanthropist, stepped in to provide food, clothing, and temporary shelter.

Despite the initial hardships, the Exodusters’ resilience and determination were extraordinary. They sought out opportunities to establish independent lives, primarily through farming. They founded all-Black towns and settlements, the most famous and enduring of which is Nicodemus in Graham County. Founded in 1877, Nicodemus was established by a group of Black colonists from Kentucky and became a beacon of Black self-governance and economic independence on the prairie. Here, Black farmers tilled the land, built churches and schools, elected their own officials, and created a vibrant community free from the direct oppression they had fled. Nicodemus, remarkably, remains the only surviving all-Black town west of the Mississippi River, a testament to the vision and fortitude of its founders.

Other settlements like Dunlap in Morris County and smaller communities near Topeka and Kansas City also flourished, albeit with varying degrees of success. The Exodusters quickly learned the harsh realities of prairie farming – drought, locust plagues, and unforgiving winters. They adapted, however, demonstrating ingenuity and an unwavering work ethic. They built sod houses, broke the tough prairie soil, and established themselves as contributing members of the Kansas economy.

Beyond economic survival, the Exodusters also pursued political and social advancement. They registered to vote, participated in local governance, and established educational institutions. The right to vote, a privilege often denied or violently suppressed in the South, was fiercely guarded and exercised in Kansas. Their presence also forced Kansas to confront its own racial attitudes, as the influx of Black migrants challenged existing social structures and sometimes provoked prejudice, though rarely on the scale of the Jim Crow South.

The Kansas Exodus was not without its critics, even among prominent African Americans. Frederick Douglass, for instance, initially opposed the movement, arguing that it diverted energy from the struggle for civil rights in the South and that Black Americans should fight for their rights where they were. However, the Exodusters’ actions were less about political strategy and more about a desperate search for immediate survival and dignity. They voted with their feet, choosing freedom over continued subjugation.

The legacy of the Kansas Exodusters is profound. They demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for self-reliance and community building in the face of immense adversity. Their migration was a powerful statement against oppression and a testament to the enduring human desire for freedom and self-determination. They laid the groundwork for future movements, serving as a precursor to the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when millions more African Americans would leave the South seeking economic opportunity and an escape from racial terror in northern and western cities.

Today, the story of the Exodusters serves as a vital reminder of a pivotal moment in American history – a time when hope, embodied in the vision of a distant prairie state, drove thousands to undertake a perilous journey for the fundamental rights of land, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Their courage, their faith, and their enduring legacy continue to inspire, illuminating the power of a people determined to shape their own destiny, even when all odds seemed stacked against them. Nicodemus, a living monument to their resolve, stands as a silent witness to a time when Kansas truly was the Promised Land for those who dared to dream of a better life.