The Great Transformation: Unearthing the Woodland Period’s Enduring Legacy

Beneath the verdant canopy of North America’s Eastern Woodlands, where rivers carve ancient paths through fertile valleys, lies the hidden narrative of a people who reshaped their world. From approximately 1000 BCE to 1000 CE, a period spanning two millennia, the Woodland people embarked on a profound transformation. They moved beyond the nomadic existence of their Archaic predecessors, laying the cultural and technological foundations that would define the continent for centuries to come. This epoch, often overshadowed by the more dramatic Mississippian cultures that followed, was a crucible of innovation, social complexity, and spiritual expression – a testament to human ingenuity and adaptation.

The Woodland Period is not a monolithic block of time but rather a dynamic tapestry woven from three distinct threads: the Early, Middle, and Late Woodland. Each phase witnessed significant developments, culminating in a vibrant and complex cultural landscape. What united these diverse groups across vast distances, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast and from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Seaboard, were three defining innovations: the widespread adoption of pottery, the increasing reliance on cultivated plants, and the construction of monumental earthworks.

Early Woodland: The Seeds of Change (c. 1000 BCE – 200 BCE)

The dawn of the Woodland Period, often termed the Early Woodland, saw the first tentative steps towards a more sedentary lifestyle. While hunting and gathering remained central to subsistence, the introduction of pottery was a game-changer. No longer were people solely reliant on perishable containers made of bark, gourds, or animal hides. Pottery allowed for more efficient cooking, processing, and storage of food, particularly wild plant resources and early cultivated crops like squash, sunflower, and sumpweed.

Early Woodland pottery, such as the rudimentary but functional vessels of the Adena culture in the Ohio Valley, was often thick-walled, tempered with grit or fiber, and relatively undecorated. Yet, its presence signifies a shift. It implies a greater investment in specific locations, as pottery is heavy and fragile, making it less suitable for highly mobile groups.

It was during this time that the first substantial earthworks began to appear. The Adena culture, centered in what is now Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky, is particularly renowned for its conical burial mounds. These mounds, often constructed over charnel houses where the dead were prepared, represent a significant communal effort and a developing reverence for ancestors. Grave Creek Mound in Moundsville, West Virginia, standing over 60 feet tall and 240 feet in diameter, is a stunning example of Adena engineering and spiritual dedication.

"The Adena," notes archaeologist Dr. N’omi Greber, "laid the groundwork for the more complex societies that would follow. Their innovations in mound building and mortuary practices show a nascent social complexity and a deep spiritual connection to their landscape and their dead." These early mounds weren’t just graves; they were markers, statements of presence, and focal points for community identity.

Middle Woodland: The Zenith of Interaction (c. 200 BCE – 500 CE)

The Middle Woodland Period, often synonymous with the remarkable Hopewell culture (though "Hopewell Interaction Sphere" is a more accurate term, as it encompasses a network of related but distinct regional groups), represents the apogee of Woodland cultural expression. This era witnessed an explosion of artistic achievement, monumental construction, and an unprecedented level of inter-regional exchange.

The most striking feature of the Hopewell Interaction Sphere was its vast trade network, stretching across much of eastern North America. Exotic materials flowed into the Ohio Valley and other Hopewell centers from incredible distances: obsidian from Yellowstone in the Rocky Mountains, copper from the Lake Superior region, mica from the Appalachian Mountains, galena from the Ozarks, and marine shells (conch, whelk) from the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. These materials were not merely traded for subsistence; they were transformed into exquisite ritual objects, effigy pipes, intricate copper plates, and delicate mica cutouts, often buried with the dead or used in elaborate ceremonies.

"This wasn’t just simple bartering," explains archaeologist Dr. Brad Lepper, a leading authority on Ohio’s ancient earthworks. "The Hopewell Interaction Sphere was about the exchange of ideas, rituals, and prestige goods that solidified social standing and spiritual connections across vast distances. It created a shared cosmological framework." The precise mechanisms of this exchange – whether through specialized traders, pilgrimages, or ritual gifting – remain subjects of ongoing research, but its impact on Hopewell society was undeniable.

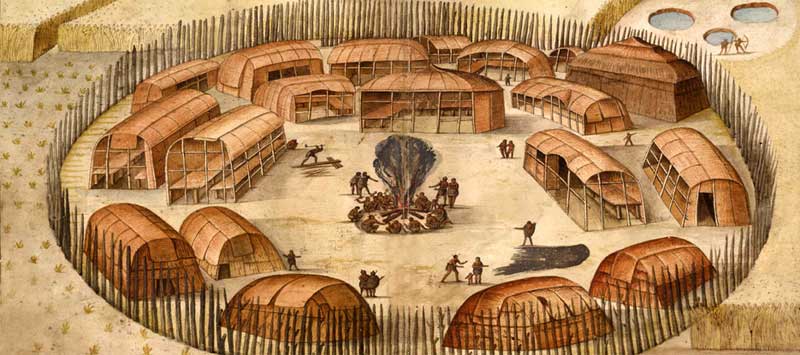

The earthworks of the Middle Woodland are perhaps its most awe-inspiring legacy. Unlike the conical burial mounds of the Adena, Hopewell people constructed immense, geometrically precise earthworks – circles, squares, octagons, and other complex shapes – often enclosing vast areas. Sites like the Newark Earthworks and Fort Ancient in Ohio are monumental feats of engineering and surveying, aligned with lunar and solar cycles. The Newark Earthworks, for instance, once covered over four square miles, its precise octagonal and circular enclosures suggesting a profound astronomical knowledge and a highly organized labor force.

These sites were not permanent settlements but rather ceremonial centers, gathering places for dispersed communities to conduct rituals, engage in trade, and bury their dead in elaborate log tombs within mounds. The burials themselves often contained a dazzling array of grave goods, indicating a developing social hierarchy and a belief in an afterlife where these objects would be useful or signify status.

Late Woodland: Adaptation and Decentralization (c. 500 CE – 1000 CE)

Around 500 CE, the grandeur of the Hopewell Interaction Sphere began to wane. The large-scale ceremonial centers were largely abandoned, the long-distance trade networks diminished, and the elaborate burial practices became less common. This shift, marking the transition to the Late Woodland Period, was likely influenced by a confluence of factors: potential climate change impacting resource availability, increasing population densities leading to resource competition, and perhaps the rise of new social or religious ideologies.

The Late Woodland is often characterized by a period of decentralization and increased regionalism. People lived in smaller, more numerous villages, and there’s evidence of increased reliance on maize agriculture, which became a staple crop in many areas, providing a more stable and calorie-rich food source. This agricultural intensification supported larger populations and more settled communities.

A significant technological innovation of this era was the widespread adoption of the bow and arrow. More efficient than the spear-thrower (atlatl), the bow and arrow revolutionized hunting, making it easier to acquire game. It also, unfortunately, made warfare more deadly and prevalent, with archaeological evidence suggesting an increase in palisaded villages and defensive structures.

While the monumental geometric earthworks largely ceased, mound building continued in different forms. In parts of the Upper Midwest, particularly Wisconsin, the Late Woodland saw the construction of effigy mounds – large earthworks shaped like animals (birds, bears, serpents, deer) or even humans. These mounds, often aligned with astronomical events or landscape features, likely served as clan markers, spiritual symbols, or commemorative monuments. Serpent Mound in Ohio, though its precise cultural affiliation is debated, represents a magnificent example of a curvilinear effigy mound, a powerful symbol etched into the landscape.

Daily Life and Enduring Legacies

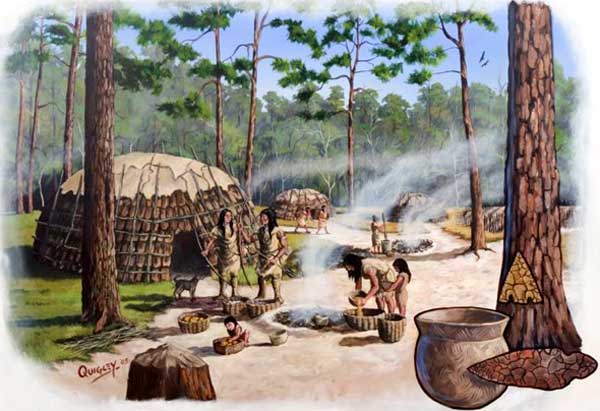

Across the Woodland Period, daily life revolved around the rhythms of the seasons. People lived in semi-permanent villages, often consisting of circular or oval houses built of poles, bark, and thatch. Their diet was a blend of wild game (deer, turkey, fish), gathered nuts and berries, and increasingly, cultivated plants like squash, sunflower, and later, maize. Pottery became more diverse, with regional styles emerging, reflecting local traditions and practical needs.

Social structures were largely kin-based, though the Hopewell period shows clear evidence of emerging social stratification, with certain individuals or families holding more prestige and power, possibly linked to their roles in ritual or trade. Spiritual beliefs were deeply intertwined with the natural world, animistic in nature, and expressed through elaborate ceremonies, mortuary practices, and the use of sacred substances like tobacco.

The Woodland Period’s legacy is profound. It represents a critical bridge between the mobile hunter-gatherers of the Archaic and the complex chiefdoms of the Mississippian. The innovations in pottery, agriculture, and earthwork construction provided the blueprint for future cultural developments. The Woodland people mastered their environment, developed sophisticated social structures, and left an indelible mark on the landscape and the cultural memory of North America.

Today, archaeologists continue to uncover the rich details of this transformative era. Through careful excavation, scientific analysis, and respectful interpretation, they piece together the lives of these ancient inhabitants, revealing their ingenuity, their spiritual depth, and their enduring connection to the land. The echoes of their ceremonies, the stories etched in their mounds, and the silent testament of their pottery remind us of a vibrant past, a time when the seeds of complex societies were sown, forever shaping the destiny of a continent. The Woodland Period, far from being a mere interlude, stands as a testament to humanity’s remarkable capacity for innovation, adaptation, and the creation of lasting cultural heritage.