The Guardians of the Grand River: Unearthing the Story of Illinois’ Indigenous People

Illinois, a state synonymous with prairie, industry, and towering cities, holds a deeper, older narrative etched into its very soil. Long before European settlers gazed upon its vast landscapes, this land was home to a vibrant and complex tapestry of indigenous cultures, most notably the Illiniwek, or Illinois Confederacy. Their story is one of profound connection to the land, sophisticated societal structures, dramatic encounters, and ultimately, a tragic disappearance from their ancestral home – a silent testament to the relentless march of history and the devastating impact of colonization.

Today, the casual observer might drive through Illinois, passing cornfields and suburban sprawl, largely unaware of the sophisticated civilizations that once thrived here. Yet, beneath the surface, in the winding rivers and ancient mounds, lie the echoes of the "Guardians of the Grand River," a people whose legacy demands to be remembered and understood.

A Confederacy of Nations: Who Were the Illiniwek?

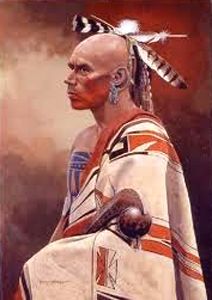

The name "Illinois" itself is a testament to this past. Derived from the Algonquian word "Illiniwek," meaning "speakers of the ordinary way" or "the men," it was the collective name for a confederacy of up to twelve distinct but related tribes. These included the Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Peoria, Michigamea, Tamaroa, and Moingwena, among others. At their zenith, prior to European contact, their territory stretched across much of present-day Illinois, parts of Missouri, Iowa, and Wisconsin, primarily centered around the Illinois River Valley and the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.

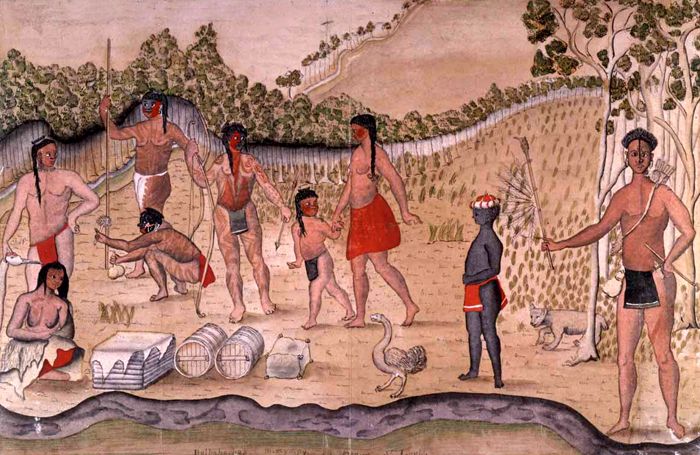

Their pre-contact world was a rich and self-sufficient one. The Illiniwek were master agriculturalists, cultivating vast fields of maize, beans, and squash, which formed the cornerstone of their diet. Supplementing this bounty, they were skilled hunters, pursuing bison on the prairies, deer in the forests, and a variety of waterfowl and fish from the abundant rivers and lakes. Their villages, often palisaded for defense, consisted of longhouses made of saplings and bark, housing extended families.

"They are people of peace," wrote Father Jacques Marquette, one of the first Europeans to encounter the Illiniwek in 1673, describing their generosity and hospitality. "They are good people, and they received us as if we had been their brothers." This initial encounter, marked by shared meals and ceremonies, offered a glimpse into a culture deeply rooted in community, spiritual reverence for the natural world, and a sophisticated social structure led by chiefs and councils.

The Echo of Cahokia: A Legacy of Grandeur

While the Illiniwek Confederacy flourished later, the region’s indigenous history boasts an even grander, albeit more enigmatic, chapter: Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Located near modern-day Collinsville, Illinois, Cahokia was the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico, a sprawling urban center that reached its peak around 1050-1200 CE. At its height, Cahokia was home to an estimated 20,000 people, a population rivaling that of London at the time.

This Mississippian culture metropolis featured over 120 mounds, including the colossal Monks Mound, a man-made earthen structure larger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Cahokia was a complex society with organized labor, astronomical knowledge (evidenced by "Woodhenge," a solar calendar), and extensive trade networks that stretched across the continent. While the direct descendants of Cahokia are debated, its influence on subsequent indigenous groups in the region, including the Illiniwek, was undeniable, showcasing a long tradition of advanced civilization in the heart of North America.

The reasons for Cahokia’s decline around 1300 CE are still debated – possibly environmental degradation, resource depletion, climate change, or internal strife. But its monumental presence serves as a powerful reminder of the sophisticated societies that preceded European arrival, a testament to human ingenuity and communal endeavor that stood for centuries before the Illiniwek emerged as the dominant force in the region.

The French Arrive: A New Era of Alliance and Conflict

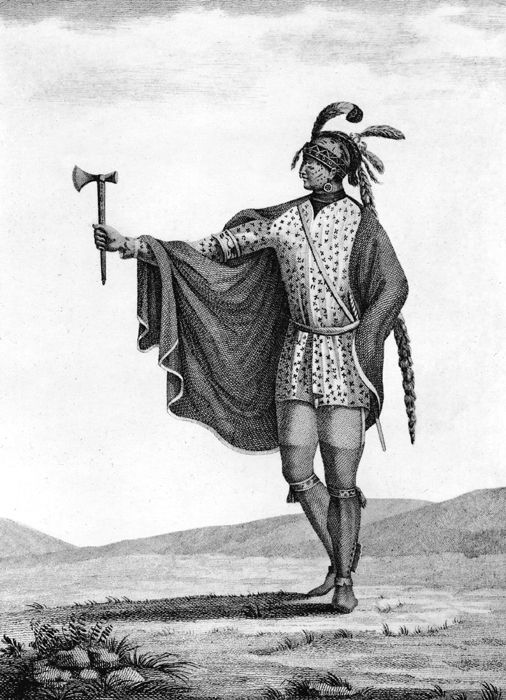

The arrival of the French in the late 17th century marked a pivotal turning point for the Illiniwek. Explorers like Marquette and Louis Jolliet were primarily interested in finding a route to the Pacific and establishing trade. The Illiniwek, initially, saw the French as potential allies against their traditional rivals, particularly the powerful Iroquois Confederacy who, armed with Dutch firearms, were pushing westward in the devastating "Beaver Wars" over control of the fur trade.

The French, eager to secure furs and expand their influence, established trading posts and missions, like Kaskaskia, which became a significant hub. This interaction brought both opportunities and profound challenges. The Illiniwek gained access to European goods – metal tools, textiles, and crucially, firearms – which altered their hunting practices and warfare.

However, contact also introduced the most insidious and devastating weapon: disease. Lacking immunity to European ailments like smallpox, measles, and influenza, the Illiniwek population was decimated. What once numbered perhaps 10,000 to 20,000 people rapidly dwindled. Historians estimate that by the early 18th century, their numbers had plummeted by as much as 90%.

As Father Gabriel Marest wrote from Kaskaskia in 1712, "The number of Savages is much diminished. They are dying daily of various diseases, and the smallpox in particular has carried off a great many." This demographic catastrophe weakened the Confederacy, making them increasingly vulnerable to both European pressures and the incursions of other tribes.

The Gathering Storm: Pressures from All Sides

The 18th century proved to be a crucible for the Illiniwek. Caught in the geopolitical struggles between France and Great Britain, and facing relentless pressure from neighboring tribes like the Sauk, Fox, Kickapoo, and Potawatomi, their existence became a struggle for survival. The balance of power shifted constantly, and the Illiniwek, weakened by disease and internal strife, found themselves increasingly outmatched.

A particularly tragic event occurred in 1769, when the legendary Ottawa chief Pontiac, a powerful figure who had led a major resistance against the British, was assassinated by a Kaskaskia warrior. This act provoked severe retaliation from Pontiac’s allies, further scattering and weakening the Illiniwek. The once-dominant Kaskaskia, for example, were reduced to a mere handful of individuals.

As American settlers began to push westward following the American Revolution, the pressure intensified. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 placed all remaining Illiniwek lands under U.S. control. The American policy of "Indian Removal" began to take shape, fueled by land hunger and a belief in Manifest Destiny.

The Vanishing Footprints: Treaties and Removal

The story of the Illiniwek in the 19th century is one of continuous land cessions and forced migration. Through a series of treaties, often signed under duress or by a few remaining leaders who no longer represented the fragmented whole, the Illiniwek tribes relinquished their ancestral territories.

The Kaskaskia, once the most prominent of the Illiniwek, signed treaties in 1803 and 1818, ceding vast tracts of land. They, along with the Peoria, Michigamea, and Cahokia, were eventually consolidated and removed. By the 1830s, the remnants of the Illiniwek Confederacy, particularly the Kaskaskia and Peoria, were compelled to move west of the Mississippi River, first to present-day Kansas, and later, to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma.

This was not a voluntary migration but a forced displacement, part of a broader pattern of ethnic cleansing that saw countless indigenous peoples uprooted from their homes. The trauma of removal, the loss of land, culture, and identity, left an indelible scar. The vibrant communities that once thrived in Illinois became a whisper in the wind, their physical presence gone, their languages fading.

The Enduring Spirit: The Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

Yet, the story does not end in complete disappearance. The resilience of the human spirit, and the deep roots of cultural identity, meant that a spark of the Illiniwek endured. Today, the direct descendants of the Kaskaskia, Peoria, Michigamea, and Cahokia tribes are federally recognized as the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma.

Based in Miami, Oklahoma, the Peoria Tribe has worked tirelessly to preserve their heritage, language (a variant of the Algonquian Miami-Illinois language), and traditions. They are a vibrant community, committed to educating others about their history and ensuring that the legacy of their ancestors, the original "Illiniwek," is never forgotten.

"We carry the spirit of our ancestors," says a tribal elder, emphasizing the unbroken chain of identity. "Though we are far from the Illinois River, our heart remains connected to that land. Our story is not just one of loss, but of survival and continuity."

Remembering the Guardians

The story of the Illiniwek Confederacy is a crucial chapter in the history of Illinois and the United States. It’s a reminder that the land beneath our feet holds layers of stories, some glorious, some tragic, all deserving of our attention. From the monumental earthworks of Cahokia to the peaceful encounters with Marquette, from the devastation of disease and warfare to the forced removals, the Illiniwek endured a journey that profoundly shaped who they are today.

As Illinois continues to grow and evolve, it is vital to look back and acknowledge the original guardians of its grand rivers and prairies. Understanding their history, recognizing their profound contributions, and acknowledging the injustices they faced is not just an act of historical remembrance, but a crucial step towards building a more complete and just understanding of our shared past and our collective future. The echoes of the Illiniwek still resonate, if only we take the time to listen.